On average, healthcare accounted for 8.6 per cent of personal spending last year, up from 6.5 per cent in 2016, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.

At the same time, the proportion of people aged 65 and over climbed from 10.8 per cent to 14.9 per cent.

Scores of retirees took to the streets in the central city of Wuhan in February to protest against cuts to their medical services.

Beijing started to turn its attention to the problem in late 2013.

That December, the then National Health and Family Planning Commission issued three lists of activities that were off limits for health institutions and professionals.

These lists regulated the procurement of medicine, medical devices and medical supplies – big-budget areas that were fertile for graft.

But there were other opportunities for eye-watering corruption in the medical system.

In 2015, Wang Tianchao, the former president of Yunnan First People’s Hospital in Kunming, was ordered to spend 10 years in jail for accepting 35 million yuan (US$4.8 million) in cash, 100 properties and a number of car parking spaces.

The Supreme People’s Procuratorate said Wang took the bribes from 2005 in return for awarding hospital construction projects, buying medical equipment and giving doctors promotions.

In the decade since those lists were issued, authorities have passed laws and amendments to try to stamp out corruption and rein in medical costs. These include bringing public hospital managers and businesses under “national supervision” and banning companies that engage in corruption from the industry.

But the government is still struggling to deliver affordable health services to its population.

Xi has made healthcare one of the livelihood issues at the centre of his “common prosperity” campaign to shore up the ruling Communist Party’s legitimacy as not only the pro-development force, but also a societal protector to keep social instability in check.

In his work report to the party’s decision-making Central Committee at the party congress in October last year, Xi listed medical care as one of many difficulties faced by the Chinese people.

It was the same message he delivered to Congress five years earlier when he named healthcare – along with education and housing – as the priorities for the new administration.

To that end, authorities have renewed attention on corrupt activities, giving people involved in medical industry graft until the end of July to turn themselves in.

After that, thousands of investigators from national anti-corruption agencies and healthcare authorities stormed the country’s hospitals, public health insurance administrations and medical suppliers.

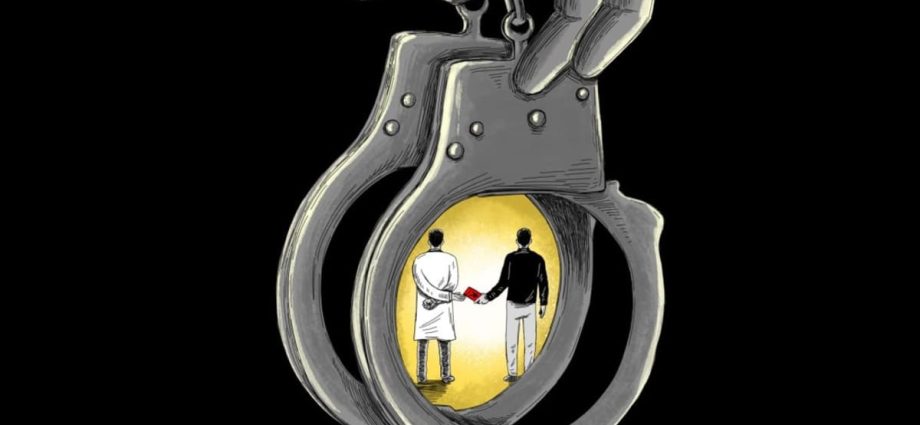

Bribery is the major form of medical corruption in China’s health system, according to a paper published in February by a group of Chinese and American researchers.

In the paper published in the Health Policy and Planning journal, the researchers said bribery accounted for 68.1 per cent of the cases of medical industry corruption listed on the China Judgments Online website between 2013 and 2019.

About 80 per cent of those taking bribes were healthcare providers, and most of those giving the kickbacks were suppliers of pharmaceuticals, medical equipment and consumables.

Beijing chose a massive anti-corruption campaign as the “breakthrough point” of its healthcare reform because graft is central to pushing up prices and inflating claims on the national insurance system, according to Xie Maosong, a senior fellow of the Taihe Institute and a senior researcher at the National Strategy Institute at Tsinghua University.

Xie said the crackdown was a long-term fight that served a number of elements of Xi’s economic and social agenda.

“It aims to bring down the cost of healthcare by squeezing out bribes, which inflates the medical bills,” he said.

“If successful, it can help ease the Chinese people’s worries about rising healthcare costs and give them more confidence to spend on other things.

“It is also a prelude to the push for a further revamp of the national healthcare system, which will cut away the middlemen between hospitals and medical suppliers.

“Beijing is very serious about these objectives and it wants to achieve them in the coming five years.”

The national crackdown on medical graft follows similar campaigns in the military, security and administrative systems.

Deng Yuwen, a former deputy editor of the Central Party School’s official newspaper Study Times, said Xi’s massive and tough anti-corruption apparatus had always moved in tandem with his policy objectives, because it has been “most potent tool” to spur the entire bureaucracy to achieve his political goals.

Deng said the initial focus of Xi’s anti-corruption campaign was to “get the key pillars of the house in order” before moving on to livelihood issues.

“You can see that Xi is very committed to fixing the problems in education, medical care and housing, because he wants to be remembered as the one who dares to deal with the most thorny problems,” he said.

“Beijing believes that fixing these issues is the prerequisite for its domestic consumption, which will drive its domestic circulation as its external trade is facing pressure from the US and its allies.

“Ultimately he wants to prove that China’s model is superior to the US, especially on healthcare.”

This article was first published on SCMP.