In my July 31 article in Asia Times, I discussed Central Asian regional dynamics, with a focus on the opposition between Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

In that context, I mentioned Kazakhstan’s efforts to halt smuggling of dual-use goods into Russia and pointed out that as a result, “a clandestine corridor has been established, passing through Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, across Turkmenistan, and finally across the Caspian Sea before reaching Russia.”

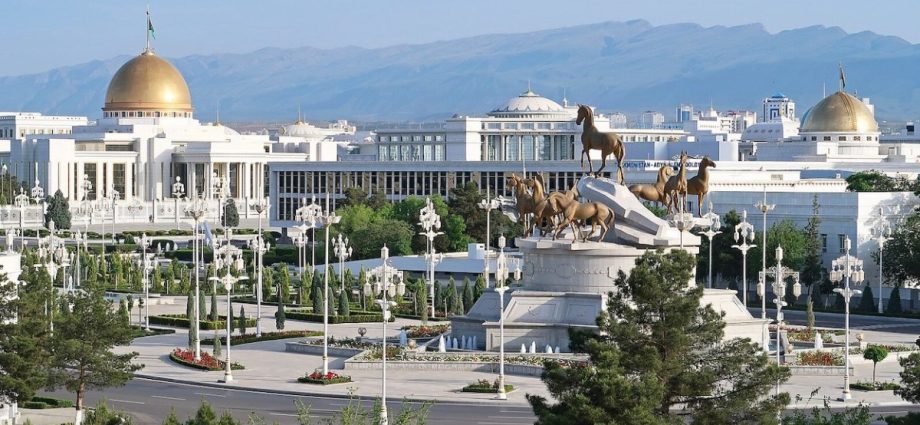

When I wrote that, it had not been officially announced that Tajik President Emomali Rahmon, Turkmen President Serdar Berdimuhamedov, and Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev would hold a summit meeting in Ashgabat on August 4.

This is the first time such a summit has taken place with representation limited to these three countries. The absence of Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and Kyrgyzstan’s Sadyr Japarov was likely due to their mutual differences over questions of regional development and cooperation. At the same time, their absence meant that the trilateral summit could not be comprehensive or make significant decisions.

None of the three participants in the summit has explained the reason for that, although the meeting did produce a joint declaration. That statement mentioned attempts to cooperate on problems in the areas of water, electricity and gas, but it remained vague concerning specific measures.

Regional transportation

However, it would be a severe omission if the three sides did not also discuss – in the context of cooperation in the political, trade and economic spheres – the construction of transport infrastructure.

For example, the trans-Afghan railway project was highly likely discussed, since all three countries border Afghanistan, where the ruling Taliban regime is a pariah to much of the international community. Railways from Uzbekistan could connect to Pakistan’s rail network through Afghanistan, although such a project would require participation by representatives not only from Afghanistan but also from Russia.

According to unofficial reports, the three countries did nevertheless discuss joint activities in logistics and transit, with special attention to the creation of a multimodal transportation route along the Tajikistan-Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan corridor. Such a corridor would facilitate circumvention of international sanctions imposed against Russia for its war against Ukraine.

Russia also continues to depend on Armenia in that connection. The European Union has recently included Armenian entities on the list of sanctions against entities “directly supporting Russia’s military and industrial complex in its war of aggression against Ukraine.”

According to data from the United Nations, in 2022 the US and the European Union exported 16 times the worth of integrated circuits to Armenia thaat they did in 2021. Armenia’s exports of ICs to Russia jumped to US$13 million in 2022 from less than $2,000 (two thousand dollars) in 2021.

Evading sanctions

A client state of Russia and an ally of Iran since independence in 1991, Armenia has, like the three Central Asian countries, in effect become a transport and logistics hub through which dual-use goods pass into Russia.

Unlike the three Central Asian countries, Armenia is a member of the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). Besides Russia, the others are Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Uzbekistan is an official observer and, like Tajikistan, has a free-trade-zone agreement with the EAEU.

Russia has been depending on other EAEU members and partners for re-export of goods prohibited by sanctions. Considering Kazakhstan’s moves to limit transit across its territory, Russia certainly welcomes the trilateral cooperation of the region’s “southern tier.”

Official Moscow appears ready to make decisions in their favor, as it has done in the case of Armenia, in exchange for maintenance of this Central Asian and trans-Caspian channel for delivery of sanctioned goods.

The Tajikistan-Uzbekistan-Turkmenistan route, which the Russian press has christened as the “Southern Transport Corridor” (STC), would avoid obstacles created by Kazakhstan’s new regime of customs verification on its border with Russia.

It would also increase the cargo (coming across the Caspian Sea from Turkmenistan) to Russia’s port at the city of Astrakhan, where Moscow has been augmenting the infrastructure over the last several years while also transferring some of its former capacity to Makhachkala in the Russian Federation’s Republic of Dagestan Republic, which is situated in the central section of the Caspian Sea’s western shore, immediately north of Azerbaijan.

Like Kyrgyzstan, with which it shares a border, Tajikistan also borders China. Dual-use goods could flow into the STC either directly from China or via Kyrgyzstan. The mountainous terrain in the region is broken by the fertile Fergana Valley, which is divided among Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

Goods could also flow from northwestern Tajikistan across southern Uzbekistan directly into Turkmenistan for transit to the Caspian Sea coast, whence again to Russia.

The STC is not necessarily altogether a negative geopolitical development, however, if shippers shift its destination from Astrakhan to Azerbaijan’s port of Alat, just south of Baku.

Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan have been working for some time, and not without success, to develop such a trans-Caspian “Middle Corridor” for onward shipment of goods to European countries. China has not yet substantially supported this Middle Corridor, which is sometimes in the West mistakenly assumed to be part of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

China may yet choose to weaken Russian influence in Central Asia further, by sponsoring or at least by utilizing such a route. Large quantities of Chinese goods already pass through Kazakhstan.

An STC terminus at Azerbaijan’s Port of Alat rather than at Russia’s Astrakhan would redistribute that traffic. It would also contribute to the stabilization of peace in the South Caucasus, especially if Armenia could be persuaded to participate in the cooperation.