The leaders of a global wildlife trafficking gang have been convicted after a four-year investigation and a trial in Nigeria.

They pleaded guilty last month to smuggling the scales of endangered African pangolins.

These “top-of-the-pyramid” traffickers were responsible for half the illegal trade in pangolin scales.

This is the story of how they were outwitted by fake buyers and sting operations – conducted by a small European charity.

Café sting

A young Vietnamese woman is on a dangerous undercover mission.

She is sitting at a table in a café somewhere in Vietnam. Across from her is one of the country’s main wildlife traffickers.

Van – not her real name – is posing as a buyer for a Chinese crime boss in a trade illegal in many parts of the world, the trafficking of pangolins which are eaten in Africa, while their scales are used in traditional medicine in Asia.

Outside, a surveillance team watches in case her cover is blown.

“I was nervous for about 20 seconds but then, after that, I thought ‘I can do this’,” she says.

Van’s contact is trying to sell her scales from what the World Wildlife Fund says is the world’s most trafficked mammal, the pangolin.

Researchers estimate that in the decade from 2010, almost a million pangolins were killed to supply trafficking networks.

All eight species – four African and four Asian – are listed as threatened, with three considered critically endangered.

Van works for the Wildlife Justice Commission, a charity set up in 2015 to disrupt criminal networks making money from wildlife trafficking.

Its lead investigator is Steve Carmody, a hard-nosed former Australian police officer who used to tackle drug gangs.

‘Living the Dream’

“My passion is to catch crooks,” he says, at the charity’s secret base in the Netherlands.

In 2018, Carmody noticed huge seizures of trafficked animal parts hidden in shipping containers en route from West Africa to Asia.

He started gathering intelligence on the Asian buyers, in an investigation called Operation Hydra.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020, it offered him a rare and unexpected opportunity.

Big-time wildlife traffickers usually stay hidden, he explains: “You may see their wives flaunting their wealth, but the main traffickers we investigate are not on social media.”

But Covid meant there were fewer shipments and, in desperation, traffickers turned to Facebook to find buyers.

“We started using multiple undercovers to talk with these guys,” Carmody says. One was Van, whom he describes as “the perfect person to take that investigation forward”.

She is softly spoken with a steely determination. Being a woman in this business is unusual, but Van says it was an advantage as traffickers were more likely to drop their guard: “They are not as suspicious as when a man approaches them.”

Over months she gained the trust of Morybinet Berete, who is from Guinea in West Africa but was based in Nigeria, the hub for the illicit trade in pangolin scales.

Berete was “living the dream”, says Carmody, “driving a nice car, there was a nice house”. The team gave him the codename Genie for their surveillance logs, because someone liked the Disney film Aladdin.

Despite the difficulties of mounting operations during the pandemic, Carmody says the job was made easier because operators like Berete tend to be business people who have drifted into crime: “They don’t have the skillsets you would see with a normal street-level drug supplier.”

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Van went undercover online, gaining the trust of Berete on WhatsApp. In one video call he can be seen walking into the yard of a compound. He points the phone’s camera at a large pile of a dozen or so sacks. One of them is opened at the top. It’s full of pangolin scales he wants to sell to Van.

There are more sacks across the yard, each stuffed with thousands of scales stripped from the carcasses of pangolins.

‘Animals mean nothing to them’

While undercover, Van had to conceal her true feelings, but two years later she remains shocked.

“A hundred thousand pangolins need to get killed for that,” she says, “I was so sad inside because I love animals. Wildlife is my passion.”

What was Morybinet Berete’s view of the beautiful, secretive creatures whose scales he and his gang were trafficking?

“He’s just doing business. The animals mean nothing to them,” says Van.

But the WhatsApp video proved to be Berete’s big mistake. Investigators used details from it to locate his address.

“It’s like Pablo Escobar telling you where he lives in Colombia, and showing the cocaine in his basement,” says Carmody.

Corruption is a major driver of wildlife crime. Carmody describes the hardest part of any global investigation as finding a “small group of dedicated law enforcement officers that can’t be bought. And once you find them, it’s like finding gold”.

In Nigeria, that means the Nigeria Customs Service (NCS).

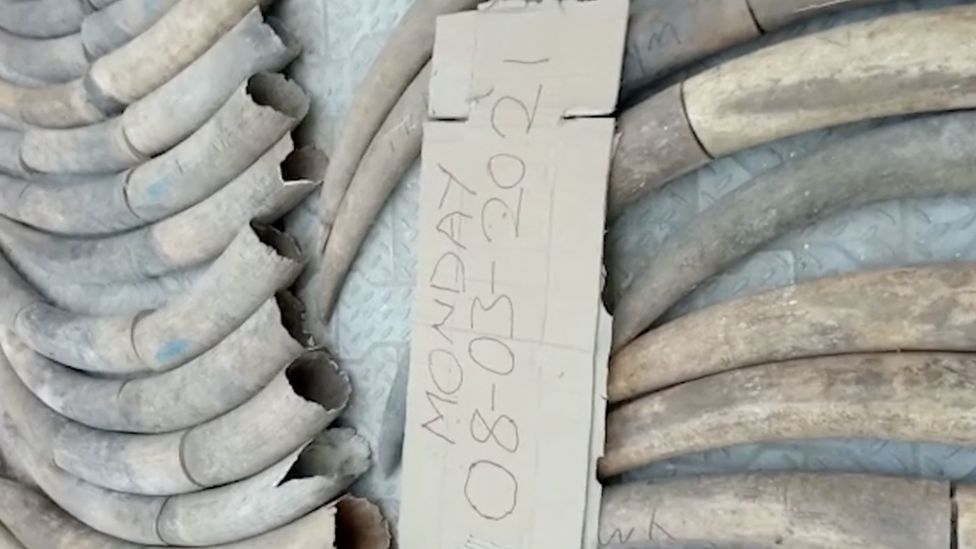

In July 2021, he tipped off NCS officials, who raided Berete’s compound in Nigeria and seized 7,000 kilos of pangolin scales, with smaller amounts of claws and elephant tusks. They arrested three men, although Morybinet Berete was not at home.

But searching the suspects’ phones led to another big breakthrough – the identities of the Asian buyers.

Big Mac and Fries

That shifted the focus of the investigation from Nigeria back to Vietnam, where a surveillance operation was mounted in March last year to follow the buyers.

The traffickers were given their own codenames. Second-in-command was Benz, thanks to the Mercedes he drove.

Ringleader Phan Chi was Big Mac because someone in the surveillance team was hungry when they named him.

Carmody laughs and says: “More embarrassingly, another co-accused is Fries.”

Pretending to be working for a Chinese buyer, Van built their trust, helping to figure out how the trafficking ring worked.

Big Mac bought trafficked scales from Berete who was now on the run in West Africa. The scales were smuggled out of Nigeria -mainly on boats – and sold on to clients in China. There, they were passed off as Asian pangolin scales, which can be legally used in traditional medicine. Shipments were often paid in cryptocurrency tied to the US dollar.

Another undercover investigator coaxed the gang into incriminating themselves. In a WhatsApp video call he asks what they want to buy. “In Nigeria only pangolin,” Big Mac responds.

Benz said he needed 20 tonnes of scales shipped to Vietnam, complaining that police had seized stock the previous summer. With the evidence mounting, the investigators were closing in.

Last May, the Vietnamese traffickers returned to Africa to buy more wildlife products. From Mozambique, Benz sent video of rhino horn he had earlier hidden in suitcases to smuggle aboard a flight.

Days later the gang arrived in Lagos, Nigeria, with Big Mac boasting in a video that he can “send a container from here”.

What he didn’t realise is that surveillance teams had been following him since his arrival in the country. The Nigeria Customs Service pounced.

Big Mac was seized in his hotel room with two phones, providing a treasure trove of evidence.

“This is a guy who did ledgers for each shipment: profit, loss, who he paid, what purpose, where it went,” says Carmody.

“It’s like you’re reading an accountant’s version of a criminal transaction. This evidence is overwhelming, linking these guys to multiple shipments of rhino horn, ivory and pangolin. Big Mac is a big deal. He’s huge.”

‘Top of the pyramid’

Phan Chi (Big Mac), Phan Quan (Benz) and Duong Thang (Fries) were charged with smuggling and trading in pangolin scales and elephant ivory.

Faced with little chance of acquittal, they admitted their guilt on the eve of a trial earlier this month. Morybinet Berete’s brother Mory also pleaded guilty. Other trials will follow.

The four men were sentenced to six years each, avoiding more time behind bars by agreeing to pay fines as part of a plea bargain.

For Steve Carmody, the convictions are ground-breaking. He says until now the focus in Africa has been on big sentences for wildlife poachers. Targeting the key players has been rare: “I can’t underestimate the value of this trial. These guys are the top of the pyramid.”

What about Morybinet Berete, aka Genie, on the run since July 2021 and facing a court order for his arrest?

“I like fishing,” says Carmody. He points to the phones on his desk: “I often throw out a few lines from different phones just to see who bites. Genie keeps biting.”

Soon Carmody, Van and the team hope to reel him in.

Additional reporting by Alex Dackevych