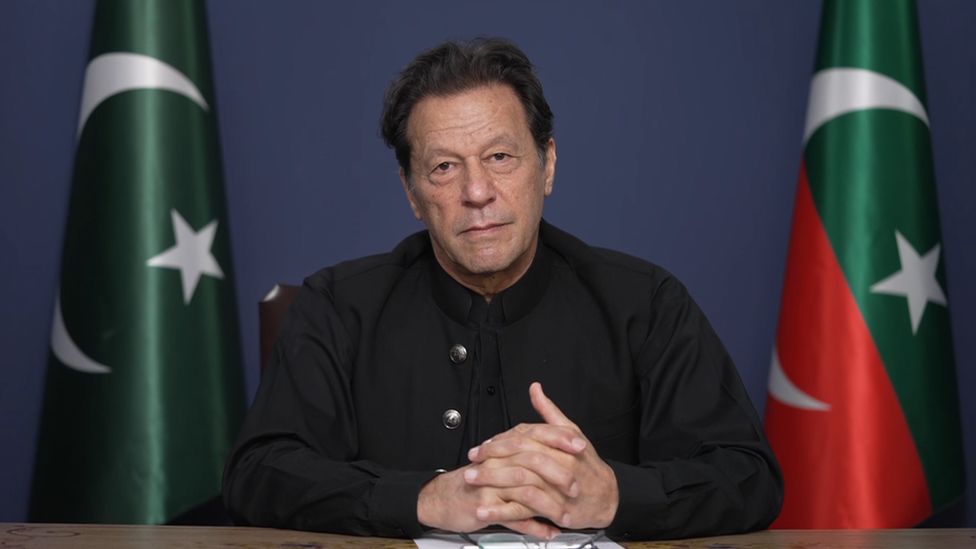

Imran Khan has been arrested for the second time in a matter of months, but this time the reaction looks very different. What could happen next?

There could not have been a starker contrast between 9 May and 5 August this year.

While Imran Khan’s first arrest led to protests in the streets from Peshawar to Karachi, with buildings burning and the army on the streets, Saturday night was no different from any other normal night in Pakistan.

Mr Khan is currently in prison, sentenced to three years for not declaring money gained by selling state gifts.

The sentence will lead to his disqualification before the upcoming elections.

His call for peaceful protests, urging people not to sit quietly in their homes, has – for now – has not worked. Why?

Ask government ministers and they will say that it is because people do not want to follow Imran Khan or his party, the PTI – unwilling to be associated with a group responsible for previous violence. That is not the message from Mr Khan’s supporters.

Imran Khan’s relationship with the establishment – shorthand in Pakistan for the politically-powerful military and intelligence agencies – soured more than a year ago.

Mr Khan was widely seen by analysts as having come to power with the help of the establishment and to have subsequently lost it when that relationship deteriorated.

Emasculated movement?

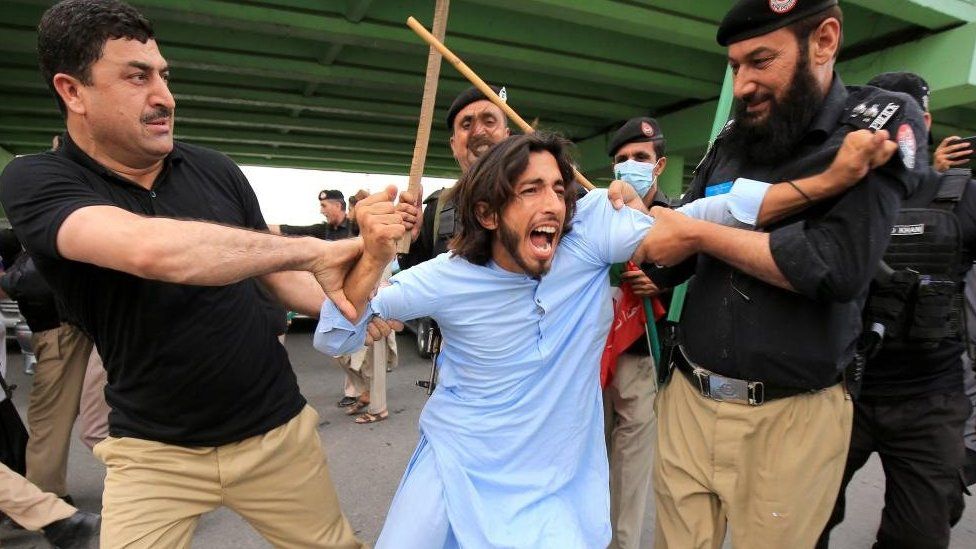

Since then, instead of waiting quietly until the next election, he has continued to criticise the army’s leadership. When army buildings were attacked following Mr Khan’s arrest in May, the military let it be known that they had a zero-tolerance approach to those they saw as responsible.

The subsequent crackdown has left Imran Khan’s party decimated.

His supporters were arrested in their thousands, and some will be tried in military courts, despite the outcry from human rights groups that the system should not be used for civilians.

Some in Pakistan’s media have told us that from late May – after TV station owners met the military – journalists were no longer allowed to say Mr Khan’s name, show his picture or even write his name on the tickertape.

Anecdotally, many previously vocal supporters told us that they had stopped posting about the PTI or its leader on social media, deleting their posts and no longer watching his public broadcasts, afraid of who might be watching them watching him.

The government has told the BBC that it does not arrest peaceful protesters. However, BBC Urdu journalists saw PTI supporters gathering outside Mr Khan’s house in Lahore on Saturday afternoon taken away by police. It is not clear if they were formally arrested.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a contact in the police told the BBC that they had arrested about 100 PTI supporters. He said that the force had been told to stay vigilant and ensure no Imran Khan supporters began gathering.

“I think the response from the draconian crackdown has scared Khan supporters into submission,” says Michael Kugelman, director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center think tank in Washington.

“I really think that the support base was unwilling to put itself at risk in the way we saw on 9 May.

“From one sense, the military has played this just right. They used these brutal tactics that really pre-empted a larger and more robust reaction from Khan’s support base.”

Imran Khan’s legal team have made it clear that they intend to appeal against the decision to jail him.

Test of the street and vote

In the course of the last few months, his lawyers have been able to repeatedly gain some temporary relief from different courts – delaying rather than stopping some of the more serious court cases.

It’s unclear if this will continue. Mr Khan saw his arrest dramatically overturned back in May, but in a very different political environment.

Imran Khan is one of several former Pakistani leaders who have ended up in the courts – Nawaz Sharif, Benazir Bhutto and the military dictator Pervez Musharraf, to name just a few in recent decades.

Mr Khan imprisoned several of his own political rivals while serving as prime minister.

Pakistan’s politicians will often say that the justice system is politically motivated against them, while justified against their opposition.

If Imran Khan remains disqualified from holding public office, there are big questions about what will happen to his party.

Mr Khan has told us previously that the PTI will live on and thrive, whether he is able to be elected or not. That is far from a certainty.

“The next big question, given the election, is how will the remaining leadership of the PTI try to mobilise?” says Mr Kugelman.

“Will they try to get their supporters out on the streets, will that be successful? It will be a good test.”

The PTI is a party created by and centred on Mr Khan. Even its logo printed on voting forms is the symbol of a cricket bat, a nod to Mr Khan’s previous career as an international cricketer.

Many of the senior political figures that surrounded Mr Khan earlier this year have since left his party. Others involved in his party are in hiding, evading arrest.

None of these suggests it would be easy for the party to run an effective political campaign.

Related Topics

-

-

10 May

-