Dissatisfaction with government. It is general and universal; systems discredited are socialist and capitalist, examples lie on both sides of the Pacific, the attitudes are on display among citizens as well as leaders. A process so widespread must find its cause in some common factor, some feature of government that is shared universally, today, and yesterday, in places antique and modern.

Can such a common failing exist, despite the thousands of years during which reformers, kings, despots, autocrats, aristos and founding fathers have been fine-tuning the subtle features of their wide range of designs for civic organization?

Yes, if we are willing to consider important reforms, on both sides of the Pacific, to the “fourth branch” of government.

The problem lies in the core feature shared by every variation of government. What is this universally shared component?

It is the fourth branch of government: bureaucracy, ministership, the Crown’s cabinet, the secretariat, the minions, the clerks, the pencil pushers – many names, it is one function that by its nature, that cannot be performed, day after day, place after place, at the level of competence, by the degree of honesty, at the rate of consistency, over the long run required of it.

To be precise, it seems to be an empirical, historical, generational fact that (for example) during an era when genius-level founding fathers gather so that they may design the intricacies of the first three branches of government, that a parallel group of super-ministers pops up, but only then, at times of great tension, crisis, to take on the task of grand form, reform and reorganization.

Once formulaic bureaucracy falls into ordinary hands, commonplace hands; once clerks become corrupt or at least careless; after office politics and self-promotion take over from public-spiritedness and the eye and pen-hand of the historians move on to other targets (as always is the empirical case), public dissatisfaction with the operations of government becomes inevitable.

Clerks or minions or some other sort of micro-level real human actors are always needed to transform the generalities announced, for example, by a lawmaker into an actual draft bill, putting into blackletter legal words the otherwise vague and imprecise intention expressed in the speeches made in the legislative chamber.

A variegated collection of other sorts of clerks are the sheriffs who enforce and the data-gathering spies who observe events, making sure rules are followed, along with the scribes who commit all to the record books.

It is an empirical fact that despite the real-world power and influence in the hands of these members of the fourth branch of government that, even in times and places such as the events in the American city of Philadelphia between 1787 and 1779, where power as distributed among the three classic branches of government was sliced and diced with great care and close, intense debate (the intellectual roots of which stretched back to ancient times), bureaucrats were, by means of simple neglect of the details of their employment and direction, allowed lifetime tenure, unchecked authority; great trust was placed in their characters and loose rules laid out to guide their discretion.

In other nations, where constitutions were allowed to grow in the manner of common law, custom, tradition, sometimes revolution and ideology, the clerks and “plumbers” who made the practical decisions that make up the real stuff of governance, grew like weeds, nearly wild in the garden of everyday events.

Kings and kingmakers

In France, Louis XIII and XIV had Cardinal Richelieu (1585-1642), succeeded by his clerk Cardinal Mazarin (1602-1661); the latter put an end to the spirit of war that threatened to disrupt the peace among the Catholic powers of the European continent.

Cardinal Wolsey (1473-1530) on the other side of the English Channel by means of his magnificent inability to manipulate the pope, Henry VIII could set the stage for British Protestantism. But once each of these “men of God” was called back to the great episcopy in the sky, much lesser men took responsibility, with ordinary mediocracy marking their efforts at imitation of their ancestors. In France it was terror; in England, Oliver Cromwell.

When leadership and management merge, mere dissatisfaction is not the problem: Gigantic processes are set in motion.

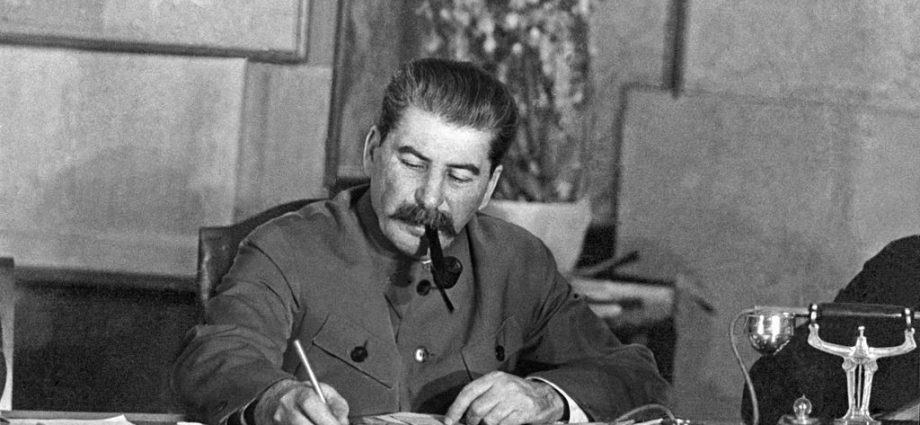

Josef Stalin was from 1922 until his death the general secretary of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party. He began his career as a clerk, assigned to his job by the undisputed leader of the revolutionary government; but once Lenin’s mortal illnesses took over, Stalin’s power transmuted from clerkship all the way to despotism by rapid steps.

Like a caterpillar who spends time in a chrysalis, becoming a mature moth, Stalin evolved from master clerk to master of all.

George Washington’s presidency was, in part, a creation of his main man, Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton’s papers on banking, his wisdom shown in nationalizing state debts, the realization he communicated to his leader that without a tariff-protected domestic economic culture based on manufacturing, the infant United States of America might just as well have scrambled back to colonial status as drawer of water and hewer of wood.

Artilleryman Hamilton brought the onetime plain-spoken General Washington to so sophisticated a political maturity that he was able to walk away from treaty obligations to France because he was shown that national interest trumps middle-class morality.

Hamilton, the first US secretary of the Treasury, opposed by James Madison, even today ranked as the (clerk) who was the Father of the Constitution, fought over whether as president, Washington had the authority to declare the US was neutral in the ongoing (1793) war between France and England, despite a treaty suggesting that the US was bound to support France.

(This high-level propaganda tussle between two of the best bureaucrats ever to face off against each other went on in essence to persuade Washington, but the back and forth documents spoke to the entire nation as well, in what is known as the Pacificus-Helvidius Debates.)

These quasi-ministerial advisers to their political masters were indeed intellectual giants, but only a few years later (1812), advisers had reverted to primitive saber-rattlers called “war hawks” who led America into a war that could have sent the new nation into a state of reconquered subjection.

Whereas Hamilton’s and Madison’s writings kept America out of war, John C Calhoun and Henry Clay (they were congressmen, technically not bureaucrats, but they whipped up public opinion so egregiously and as de facto ministers) browbeat president James Madison so artfully that he signed a declaration of war against superpower England. The result was the burning of the White House by rampaging British troops at the low point of the War of 1812.

The Chinese experience

The Chinese imperial civil-service system lasted more than 2,000 years; it featured a many-layered hierarchical structure of competitive exams, beginning at provincial level and reaching up to the Palace exams, producing an elite phalanx of selectees, who were subject to continuing exams and other testing routines that featured surprise tests.

Personnel were “farmed out” to provincial and other lesser postings before they graduated to serve the emperor. Some historians say the entire tradition of Empire relied for its longevity on the degree of expertise developed among Chinese bureaucracy. If there was a fault in the system, it was that it produced a class of ministers too remote from the lives of ordinary citizens to attract either criticism or support.

Certainly, the sense of revolutionary resistance that was a feature of Western civil-service systems did not feature prominently in the historical records of the accomplishments of this way of life, which included widespread literacy, a semi-mythical credit for the invention of paper, and a naval force that came within a single counter-directive of discovering the North American continent.

For the purposes of this article, I say the Chinese civil service was a “fourth branch” of government, and it produced stability rather than the reverse. The reason for the contrast in effect was the elaborate “constitutional” level of thoughtful design that was in evidence in its structure, which stands in contrast to typical Western systems, that featured nepotism, aristocratic membership requirements and (by comparison) near random processes by which they were maintained.

And so, in the history of nations, bureaucrats must have been the ones who carved into a black, finger-shaped solid stone stele the Code of Hammurabi, yet their names were known to history only rarely.

Once the times “revert to the mean,” the practical operation of civil organization and process, from the interpretation of law codes to the day-to-day reality of civil society was managed by political flunkeys notable for mediocracy. That is, once “normal times” are re-established, so both politicians and their servants become degenerate.

What may be said about the cross-Pacific contrast in “fourth branch” design?

A merger between the two blueprints cries out for adoption. In the West, no more lifetime tenure, no more political tests for appointees, civil-service exams that are highly selective, retesting on a regular, as well as on a surprise, basis, a thin layer at the top where loyalty to the day’s party-in-power is explicit, but no such loyalty tests “downstream,” a degree on unanimity, but combined with integrity and a spirit of duty-first.

In modern China, a willingness to remember and adopt the rectitude of the Imperial system, especially with respect to probity rather than ideological tests. A regularization of tests to eliminate (insofar as reasonable) corruption, it being replaced with a sense of patriotic duty and long-term loyalty to some kind of non-partisan single-mindedness to constitutional politics rather than party loyalty.

In the past, a sharing of power at the top was stabilizing. As in the past, doors should remain open so that ordinary people with extraordinary endowments of skill, honesty, dutifulness and goal-associated persistence are made especially welcome.

On both sides of the Pacific such reforms are lofty in ambition. But that fourth branch of government, if better designed, would yield great dividends in both places.

Tom Velk is a libertarian-leaning American economist who writes and lives in Montreal, Canada. He has served as visiting professor at the Board of Governors of the US Federal Reserve system, at the US Congress and as the chairman of the North American Studies program at McGill University and a professor in that university’s Economics Department.