When 17-year-old Manoj – who was recorded female sex at birth – told his family that he felt like a man and loved a woman, he almost got killed.

He says his parents refused to accept him, tied his hands and feet, beat him up badly and locked him up in a corner of the house. His father threatened to kill him.

“The violence was beyond anything I had imagined,” he says.

“I had thought whatever be my truth, I would be accepted, after all this was my family. But my parents were ready to kill me for their honour.”

For a woman in rural India, wanting to assert the right to identify as a trans man could lead to sharp retaliation.

Manoj says he was pulled out of the village school in one of India’s poorest states – Bihar in northern India – and forcibly married to a man twice his age.

“I even contemplated taking my own life, but my girlfriend stood by me through it all. That I am alive, and we are together now, is because she didn’t give up on me,” he says.

Now 22, and hiding in a big city for the past year, Manoj and his girlfriend, Rashmi, are eagerly awaiting the Supreme Court’s verdict on their petition asking for the legal right to marry.

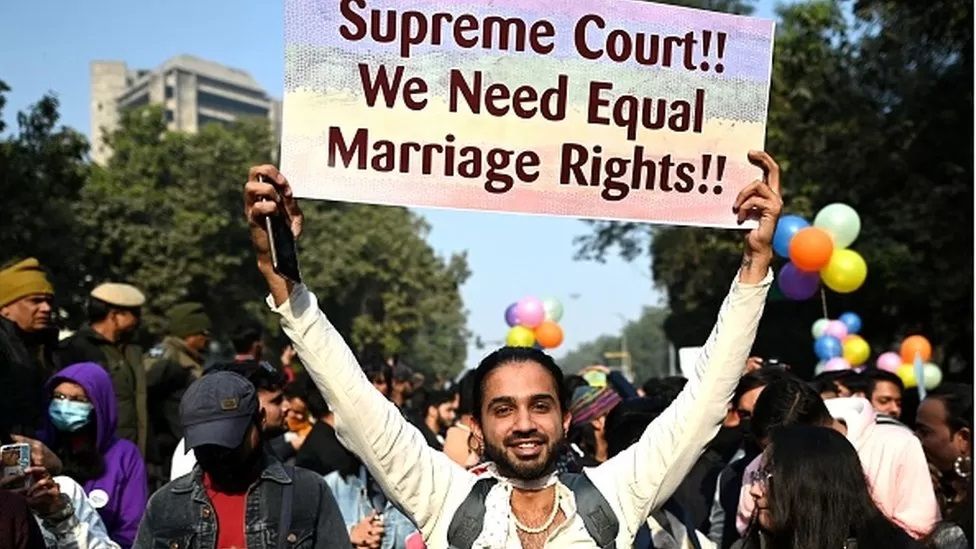

India decriminalised gay sex in 2018, but same-sex marriages are still not recognised. The Supreme Court heard 21 petitions asking for legalisation this year and a ruling is expected soon.

While others have argued for the right to marry as a matter of equality, Manoj and Rashmi’s petition, filed jointly with two couples and four LGBTQ+ feminist activists, asserts that marriage is a way out of the brutal physical and mental violence inflicted on them by their own families.

“Legal recognition of our relationship is the only way out of this life of fear,” Manoj says.

India has half-a-million transgender people, as counted in the last census in 2011, a number that activists believe is a gross underestimation.

In 2014, the Supreme Court had ruled that trans people be recognised as the third gender. Five years later, India passed a law that prohibits discrimination in education, employment, healthcare and criminalises offences against them, including physical, sexual, emotional and economic abuse.

But violence from families is a complex challenge.

Violent families

Most laws and the society perceive family by blood, marriage, or adoption as the safest space for individuals, says Mumbai-based feminist lawyer Veena Gowda.

“Familial violence is not unknown to any of us, be it against the wife, children, or queer trans people. But it is made consciously invisible, as seeing it and acknowledging it would mean questioning the very institution of ‘family’,” she says.

Ms Gowda was part of a panel comprising a retired judge, lawyers, academicians, activists and a government social worker that heard detailed testimonies of familial violence faced by 31 people from the LGBTQ+ community in a closed-door public hearing.

Its findings were published in April this year in a report titled, ‘Apno ka bahut lagta hai’ (Our own hurt us the most) that recommended that LGBTQ+ people be given the right to choose their own family.

“Seeing the nature of violence faced by the testifiers, it would amount to denying them their very right to life and life with dignity if they do not have a right to choose their own family, free from violence,” Ms Gowda says.

“The right to marry would be a way of creating this new family and redefining it.”

A few months after his forced marriage, Manoj tried to get together again with Rashmi, but was tracked down by his “spouse”, who he says threatened to sexually assault both of them.

They escaped to the nearest railway station and boarded the first train that was leaving but he says they were found by their family and brought home to a fresh round of beatings.

“He was being forced to sign a ‘suicide letter’ that blamed me for his death,” Rashmi recounts.

Manoj’s resistance meant he was locked up again and his mobile phone taken away.

It was only after Rashmi contacted a LGBTQ+ feminist resource group and the women cell of the local police that they were able to get protection and escape Manoj’s family home.

They moved into a government shelter for trans people but had to move out soon as Rashmi is not a transgender person.

Escape and survival

Manoj was also able to get a divorce. But support systems that help in escaping violent families and building a new life are few.

Koyel Ghosh, who uses “they” and “them” as personal pronouns, is the managing trustee of Sappho for Equality, the first Lesbian-Bisexual-Transmasculine people rights collective in eastern India that started two decades ago. They remember clearly the day in 2020 they got a helpline call about a couple who had run away to a city in eastern India but then had to sleep on the footpath for seven nights.

“We rented a space and put them there so that they had temporary shelter for three months and they could focus on getting a job as that is the only way they can build a new life,” Koyel says.

Apart from social stigma, the threat of violence at home, disrupted education and forced marriages, many trans people also struggle to find stable employment.

India’s last census showed that their literacy rate at 49.76% was much lower than the country’s 74.04%.

According to a survey of 900 trans people in Delhi and Uttar Pradesh by the National Human Rights Commission in 2017, 96% had been denied jobs or forced into begging and sex work.

Saphho has set up a shelter to help runaway couples rebuild their lives – 35 couples have been housed there in the past two years.

It’s tough work. Koyel gets three to five distress calls daily and regularly reaches out to a support network of lawyers to find solutions.

“I have received death threats, faced mobs in villages, hostility in police stations because I am also open with my queer identity and they just can’t deal with it,” Koyel says.

When Asif, a trans man, and his girlfriend, Samina, reached out to Koyel, they were at their local police station in a village in eastern India.

Samina alleges that the constables called her a eunuch and said she should have died instead of going public with her relationship.

Childhood friends-turned-lovers, they had fled their families twice before but were brought back. This was their last chance to escape and they needed support.

“It was only when Koyel arrived that the police’s bad behaviour stopped. A senior officer chided their juniors for their prejudice and ignorance of laws as public servants,” Samina says.

Now living safely in a big city, the couple are co-petitioners with Manoj and Rashmi in the Supreme Court.

“We are happy now. But we need that piece of paper, a marriage certificate, to deter our families and community with fear of penalties or police action,” Asif says.

“If the Supreme Court doesn’t help us, we may have to die. We will never be accepted as we are, will remain on the run, always afraid of being separated,” he says.

Names of petitioners have been changed to protect their identities.

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: