It is a discomfiting fact that even in democracies, heads of government who have held power for 10 or more years convince themselves that they have the job for life.

Narendra Modi, Vladimir Putin, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Viktor Orban and Benjamin Netanyahu, to name but a few, assume grandiose delusions of permanence and concomitant infallibility.

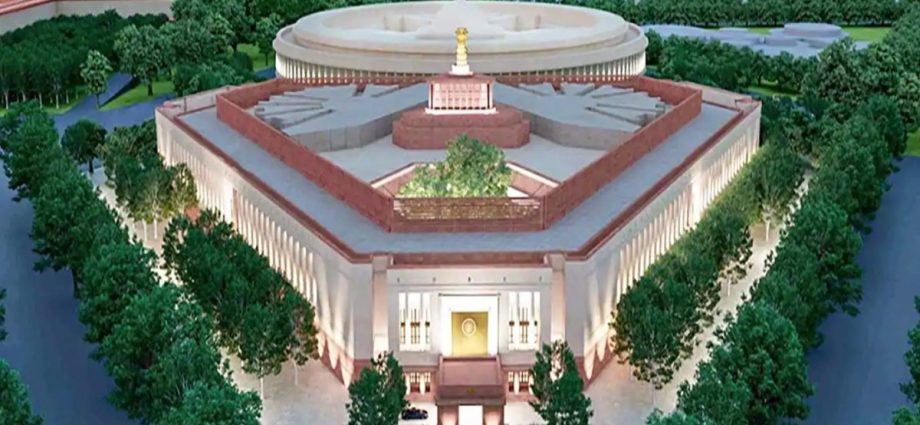

India’s striking new Parliament Building boasts a mural that, according to Parliamentary Affairs Minister Pralhad Joshi, illustrates Akhanda Bharat, undivided India. By accident or design, take your pick, this includes Pakistan, Bangladesh and part of Nepal.

The eminently foreseeable objections voiced by Pakistan and Bangladesh have stirred up vociferous Hindu nationalist support for the depiction among Modi’s followers in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

A spokesman for India’s Foreign Ministry explains, rather curiously, that the mural depicts the ancient Mauryan Empire under the governance of Ashoka.

The reason for the curiosity is that in about 240 BCE, Ashoka unified the subcontinent’s various kingdoms into a Buddhist empire, displacing Brahmin (that is, Hindu) rule.

As the late scholar Charles Allen wrote, “Much as Ashoka’s personal devotion to Buddhism had grown, in matters of state he continued to maintain an even hand – ‘I have honored all religions with various honors’ … promoting a Dharma based on ethics rather than anything that might be described as religious practice.”

For the following six to seven centuries Buddhism blossomed and became the predominant faith for much of the population of the Mauryan Empire.

Part of Ashoka’s strategy for spreading this concept was erecting pillars or inscribing stones with Buddhist mantras that prescribed a way of living that refuted religious precepts founded on the Hindu philosophy of an inherent Brahmin superiority and consequential inferiority of other categories of people.

Ashoka’s Rock Edicts promote public and private morality not religion or religious practice.

The Indian parliamentary mural, as far as one can tell from pictures of it, seems to identify the location of Ashoka’s pillars and Rock Edicts and, as such, contradicts the attempts of the BJP to harness it as indicating the past glories of an all-enveloping Hindusthan, their implicit message being, one concludes that this is the direction in which India should travel.

Most certainly, invoking the Mauryan Empire of Ashoka flies in the face of the concept of exclusive religious and political dominion by one caste and creed.

Moreover, in his conversion to Buddhism, Ashoka underwent a fundamental change from being a ruthless and savage Hindu ruler to a man who bent his considerable power and influence to bringing the enlightenment of the Dharma to every corner of the land he governed.

Again, as Charles Allen observes, by propagating Buddhism throughout the subcontinent and beyond, even reshaping it to some degree, Ashoka transformed a minor sect into a world religion.

Ashoka’s focus on ethics contrasts rather strikingly with the Modi government’s public image: Of the 543 members of the Indian Parliament, no fewer than 116 BJP MPs face criminal charges ranging from abduction to theft and attempting to cause death or grievous injury.

There is an unnerving similarity among demagogic leaders of democracies like Modi, Erdogan, Donald Trump and Boris Johnson.

In reliance on subservient or suppressed media, a close circle of dependent sycophants and impractical promises made to relatively unsophisticated electorates, these men pervert the political process.

The ultimate check on untrammeled power should be an independent judiciary; hence that is an institution that has to be emasculated, just as Orban did and Netanyahu is trying to do, or rigged à la Trump and the US Supreme Court.

Emperor syndrome is alive, toxic and subverting the democracies.

The leader of the world’s largest democracy would do well to study history before assuming a permanent mantle of office.

Neville Sarony QC is a noted Hong Kong lawyer.