If China’s neighbours, near and far, could have sent Presidents Xi Jinping and Joe Biden a text in the last 48 hours, it would probably have been some version of: “Can you two please sort things out?”

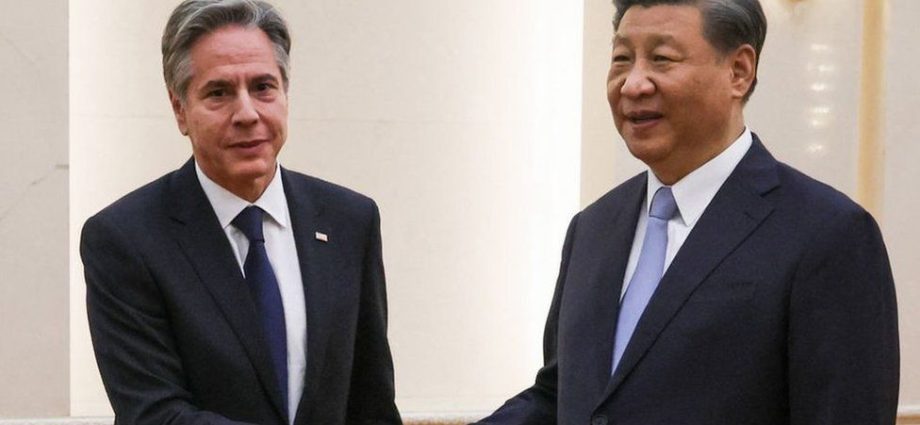

Of course, the entire world was watching US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s visit to Beijing over the weekend – but perhaps none more so than the countries that would be on the frontlines of any conflict between the US and China.

For 35 minutes on Monday, when Mr Blinken became the top-ranking US diplomat to meet Mr Xi since 2018, a collective sigh of relief was likely heaved through that tactical stretch of US allies in the Pacific – from Japan and South Korea in the north, through the Philippines, all the way to Australia in the south. Southeast Asian economies sitting on crucial global supply routes, and tiny Pacific island nations, pulled between Chinese and American overtures, would have been just as reassured.

“Everyone is learning to live with China-US rivalry, but no-one wants to choose between them,” says John Delury, Professor of Chinese Studies at Seoul’s Yonsei University. “There will be some relief to see these two countries acting like grown-ups.”

That certainly seemed to be the message both sides sought to send. Over two days, Mr Blinken met China’s top diplomats Wang Yi and Qin Gang – the latter for several hours, including a “working dinner” – before finally sitting down with Mr Xi in the Great Hall of The People.

By the end of it Mr Xi hailed “progress” in the talks and spoke of “agreements on specific issues”, without saying what those were. Back in Washington DC, Mr Biden praised Mr Blinken for doing “a hell of a job”. But the 61-year-old secretary of state, ever the pragmatic diplomat, told reporters that he was “clear-eyed” about China. He welcomed the reopening of high-level communication, and said the Chinese agreed with the Americans that ties must stabilise, but he also admitted that there were “many issues on which we profoundly – even vehemently – disagree”.

And yet the lacklustre readouts, with no breakthroughs and plenty of qualifiers, have been greeted with hope, rather than disappointment. That’s how low expectations were.

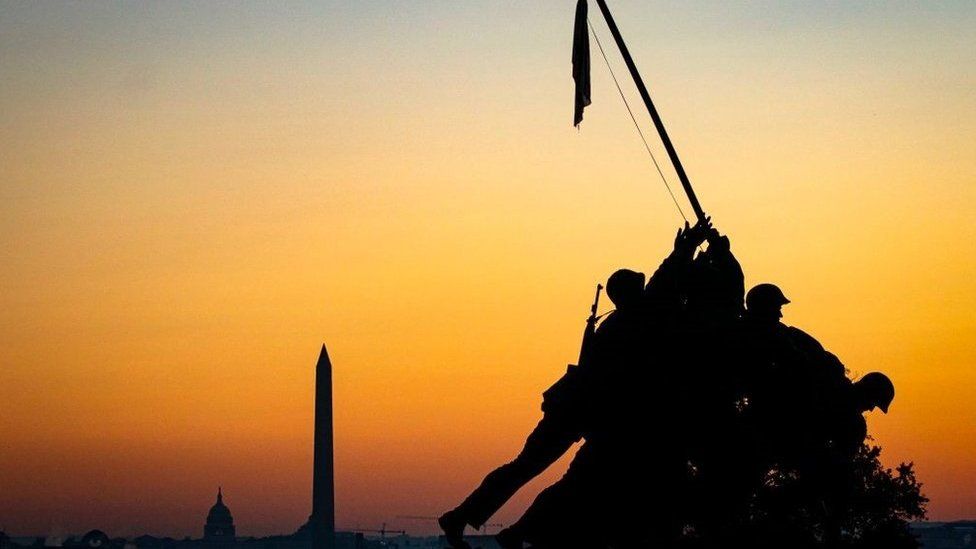

Relations between Washington and Beijing have been so fraught that the Americans came hoping to avert a conflict, a growing risk that has alarmed the region.

A recent survey by the Eurasia Group Foundation suggests that more than 90% of the respondents in South Korea, the Philippines and Singapore are “worried” about a confrontation between the two superpowers. Almost half of those asked chose regional tensions as the most pressing challenge facing their country.

“The world does not want to see this relationship spiral out of control,” said Bonnie Glaser, managing director of the German Marshall Fund’s Indo-Pacific Program. “There has been anxiety in the region and beyond that the US and China were not talking – countries want to know that if there were to be an accident, the two sides could avoid escalation.”

This is no longer playground politics. It has even gone well beyond concerns about global trade and semiconductor supplies. It has become a battle for influence that is forcing countries in the region to make tough choices about their own security.

South Korea and Japan have been American allies for decades, but historical grievances have kept them apart. Now Beijing’s growing assertiveness, coupled with North Korea’s record missile launches, has produced a necessary thaw as they face the same escalating threats.

Driven by a similar urgency, the Philippines has allowed the US access to more military bases. Tokyo is also reportedly preparing military aid for Manila – a move that could bring the Japanese back to Philippine shores for the first time since World War Two.

The ripples go as far as the Pacific Islands, where the US and China are trying to gain a strategic foothold. Washington signed a new security pact with Papua New Guinea in May after Beijing did the same with the Solomon Islands.

What many of these countries would most like to see is the resumption of a military hotline between Beijing and the Pentagon. Mr Blinken pushed for this in his meetings, but the Chinese, it seems, did not agree. The region is particularly on edge that the two could clash militarily over the self-governed island of Taiwan, which China claims as its own.

With increased military presence in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait, the risk of a miscalculation is higher than ever, especially as the US and China skirt close enough in the sky, and in the waters below.

“We need reliable communication channels. We need to reduce the risk of a military accident,” Ms Glaser said.

For countries in the Asia-Pacific, the meeting is only a start, and a tentative one at that. But, for now, they will take any amount of progress that is possible. Even if all that means is being able to take breath.

“This visit doesn’t guarantee anything, but it at least shows the US and China trying to defuse tensions and maintain dialogue, which is a good look in this part of the world,” Mr Delury said.

But the biggest challenge still lies ahead. Beijing has made it clear that Taiwan lies at the “core” of their interests. So the question is what happens next between the world’s two largest economies – and nuclear powers?

The problem for Washington is the clock is ticking as another election looms. President Biden’s Republican rivals have accused him of being soft on China. He may be tempted to show he can stand up to Mr Xi rather than alongside him.

“If the relationship is to be stabilised,” Ms Glaser says, “It has be now.”

Related Topics

-

-

14 hours ago

-