The largest ever military exercises between the United States and the Philippines are drawing to a close. They began just days after China’s military rehearsed a blockade of Taiwan – a display the US called disproportionate. With tensions high in the region, a handful of people on a few small islands find themselves caught between two superpowers.

Life is fragile in Itbayat.

The steep limestone cliffs and rolling hills that make up this tiny island on the northern edge of the Philippines rise out of the Luzon Strait.

Even on a good day, strong waves on the azure seas toss around tiny fishing boats hoping to hook some of the islanders’ favourite flying fish.

Nearly 3,000 native Ivatans, fishermen and farmers, have survived here in the face of earthquakes, typhoons and drought. But now they face a new and different threat.

Their island home risks being caught in a conflict between the United States and China as the two militaries skirt ever closer to each other to gain the upper hand in the South China Sea.

At the heart of the issue is Taiwan. China’s claims over the self-governing island are growing louder even as the US’ commitment to defend it appears to be deepening.

And these islands – Itbayat and Basco – that make up the far-flung Philippine archipelago of Batanes are in the line of crossfire.

They appear as mere dots in the ocean that surrounds them. But their proximity to Taiwan – it’s just 156km (96 miles) from Itbayat – has made them both strategic allies and vulnerable foes.

Analysts often talk of rising tensions between the two superpowers, but what is it like to live in the biggest flashpoint between Beijing and Washington?

Itbayat can often be cut off for weeks. It certainly looks impenetrable. Small ports are carved out of the cliffs and getting to a boat involves clambering down steep steps cut into the rock face.

The colour of the water hugging the land is a deep turquoise – and so clear you can watch small fish play amongst the coral. Itbayat feels untouched by man, other than the indigenous community who’ve made it their home.

Few here have televisions. A network of relayed messages from house to house, or through the church congregation is often more reliable than the patchy phone signal.

But they don’t need TV news or social media to tell them about the turbulent relationship between the US and China which threatens their shores.

It’s closer than it has ever been.

Who rules the waves?

Crouched down, eyes fixed through the viewfinders of their weapons and head to toe in camouflage are the members of the US Army’s 25th Infantry Division training on the island of Basco.

They are practising to defend the island from potential aggressors. The exercise is part of the largest combat drills ever held between the US and the Philippines.

Out at sea, the mission was controlled from the USS Miguel Keith, a naval ship, while V-22 Osprey aircraft hovered over the island, much to the amazement of locals who grabbed their mobile phones to film. The simulation even involved rocket launchers being shipped to the beaches using amphibious landing craft.

“The goal of our campaign in this region is to deter conflict from ever occurring,” says Major General Joseph Ryan, the commanding general of the 25th Infantry Division.

“We don’t want a war with the PRC [People’s Republic of China]. We do not want that, we do not desire that and we are not provoking that. A war with the PRC is good for nobody.”

But, he admits, the two forces are sending a message.

“The message sent is we’re ready, we’re capable, we’re prepared. We’ve got a great partnership here. And we mean business.”

The two sides are certainly arming themselves; as is the whole of Asia.

China is still the region’s biggest spender on new military hardware, with this year’s defence budget the highest it’s ever been, around $224bn.

The US, in turn, has been keen to show off its capabilities, holding ever more military drills with allies throughout the region, including Japan, South Korea and Australia.

For Washington this is not just about a display of shiny new arms. It is also about shoring up alliances – the White House has been dispatching envoys more often than usual to Asia, hoping to stitch together a sturdy coalition to counter China. And that includes the Philippines, whose location is an asset.

“The situation is heating up,” admitted Filipino President Ferdinand Marcos in a recent interview with a local radio station ahead of his visit to Washington this week.

He has decided to take a more assertive approach to China than his predecessor and that includes ordering more patrols by the Navy and the Coastguard.

Fishermen on the frontlines

But what would be largely uneventful patrols elsewhere have the potential to turn into a conflict in the South China Sea, where even fishing could ignite a geopolitical crisis.

Beijing claims sovereignty over almost the entire South China Sea – a strategic waterway through which trillions of dollars in trade passes annually – despite an international court ruling that the assertion has no legal basis.

“The Chinese fishermen used to harass us,” says 59-year-old Cyrus Malupa, as he casts a single wire line with a metal hook into the sea.

“But when we reported that to the government, it placed a military base on Mavulis Island to the north. Now we have Philippine Marines there on duty,” he adds.

In March, the Navy started a month-long mission on the uninhabited island, described it as the country’s “first line of defence” and raised the Filipino flag on its highest peak. A small but bold act of sovereignty.

For Cyrus and others who live in tiny boats for days in the hope of catching enough tuna to sell at the local market, the geopolitical dispute is personal. It’s about feeding their families.

Hundreds of Filipino fishermen have reported incidents of being driven away from their traditional fishing grounds in the South China Sea for more than a decade – particularly in the contested seas near the Spratly Islands.

“We don’t have that much catch because the poachers have more advanced technology,” Cyrus says as the tiny boat bounces over the white horses now forming on the water.

“Us locals use the old way of fishing like lines and smaller nets. But the poachers have more advanced technology so they can catch as much as they can.”

Manila has filed nearly 200 diplomatic protests against Beijing’s actions in the South China Sea – where Vietnam, Taiwan and Brunei also have overlapping territorial claims.

It’s natural to be worried because any conflict will affect our lives,” said 51-year-old Victor Gonzales.

“First, we are afraid for our lives and then there is the possible exodus of people coming here from Taiwan as we have limited resources.”

Like most on Itbayat, Victor farms when the sea is rough and goes out to fish when it is fair. Crops are raised by hand, with no help from machinery or fertilisers. Instead, farmers rotate sweet potato, rice, corn, garlic and onions. A single farm can feed around 25 families.

“We need to protect our resources because it’s how we live, and we don’t have any alternative. We want to have something to pass onto the next generation,” Victor says.

The concern runs deep enough that leaders of local governments in the Batanes islands announced to reporters last December that they would secure food supplies to prepare for a possible conflict.

Arms and allies

The restricted signs around the Camilo Osias naval base on the beaches of Santa Ana are hand-painted and difficult to make out – almost obscured by the dozens of green fishing boats moored along the sand. It’s Sunday and a few of the men who would usually be at sea are getting tipsy in the shade on a Filipino brand of gin.

A handful of water buffalo wallow in the shallows flicking off the birds that come to rest on their backs with their tails. Nearby, women are doing the weekly washing in huge tubs – the suds spilling over the sides.

Santa Ana is a sleepy town on the northern tip of the main island of Luzon. There is little activity around the tiny Filipino naval base which is so tucked away on a corner of the beach that you would barely know it was there – unless you spotted the “restricted” signs. Crucially it has an airstrip that will give the US access to the Taiwan Strait.

“It’s not really a base. I would say it is more like a Boy Scout camp,” exclaims Cagayan Governor Manuel Mamba.

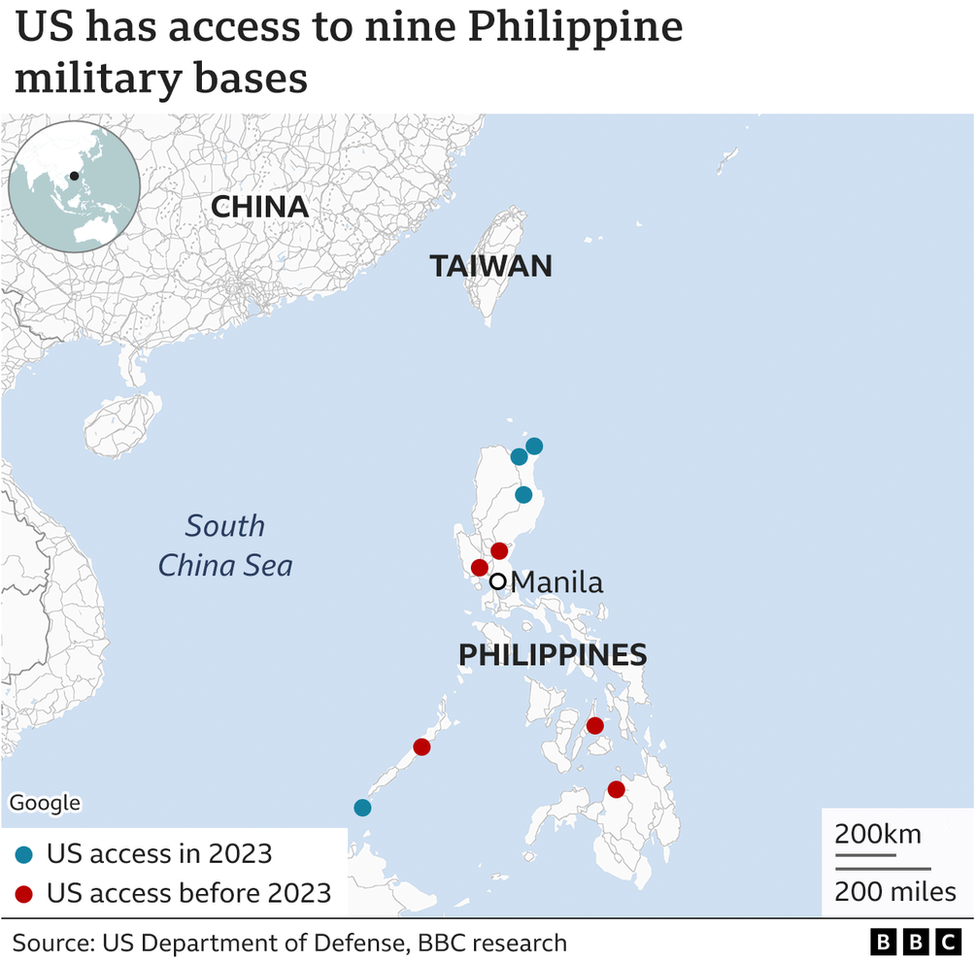

This is one of the four new bases in the Philippines that US troops can access as the two countries boost their military alliance. Two of the new locations are in the northern province of Cagayan and face Taiwan.

“This is not my call or the call of our people. It’s the call of our national leaders. We will abide by it. We may disagree with it, but really it’s all because we don’t want war,” says Mr Mamba.

“We are poor, and we have our local problems too. That is why any cause of uncertainty will be a bigger problem for all of us.”

Mr Mamba is worried that having two US bases in his province will make it a target. He had hoped to bring Chinese tourists to the region, or build a new international airport. Now he fears that Beijing may snub the Philippines when it needs their business more than ever.

“It is hard for us to choose between the two of them. Between a neighbour who has never been our enemy and an ally who has stood by us through so many difficulties. If they could be together, if only they could talk, if only there was middle ground for them to meet.”

Governor Mamba’s comments reflect a growing anxiety across parts of Asia. Will they be forced to choose between a long standing ally, the US, and their largest trade partner, China?

Back in Basco, in the capital of the tiny Philippine province of the Batanes islands, 21-year-old Ave Marie Garcia is helping travellers get flights to and from her home island of Itbayat.

She doesn’t keep an eye on the news – but she couldn’t fail to notice or hear about the latest military exercises.

“I don’t think the US is going to cause war with these military exercises. It’s just the US is trying to help the Philippine military to protect this island and to let the Chinese know that this region is protected,” she says as she jumps on her scooter to show us her favourite views and beaches.

Ave is one of 11 children and like many in the Philippines, her mother works abroad to send money back to the family.

Their ancestral home, a traditional stone cottage which has stood through the centuries, lies in ruins after an earthquake in 2019 – a reminder that life is fragile here.

Ave and her siblings were brought up by what she describes as her strict grandmother. But in Ave there are small signs of rebellion. Her long dark hair is dip-dyed blonde at the ends.

And yet, she is an Ivatan at heart. Her hope is to preserve her ancestors’ way of life, even if that means saying no to the United States. She believes there should be limits.

“I am worried about the future – for our future. I hope they won’t build structures here for the U.S military, I just want to leave it as it is. They are allowed to visit this place but they are not allowed to build something here that will cause anyone to invade us. For me it’s scary.”

The people here feel miles away from the politics and the bellicose rhetoric, and they try not to dwell on what could be, and enjoy what they have.

“An island life is a simple life,” Ave says. Each day, she and her family pray it will stay that way.