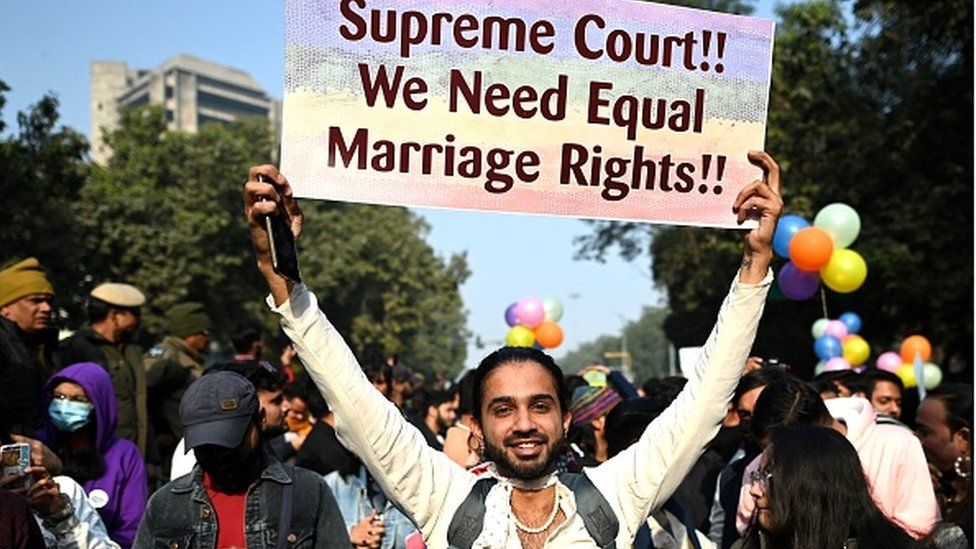

On Tuesday, India’s Supreme Court will start hearing final arguments on a number of petitions seeking to legalise same-sex marriage. The court has said the hearing will be “livestreamed in public interest”.

With same sex couples and LGBTQ+ activists hoping for a judgement in their favour and the government and religious leaders strongly opposing same sex union, the debate is expected to be a lively one.

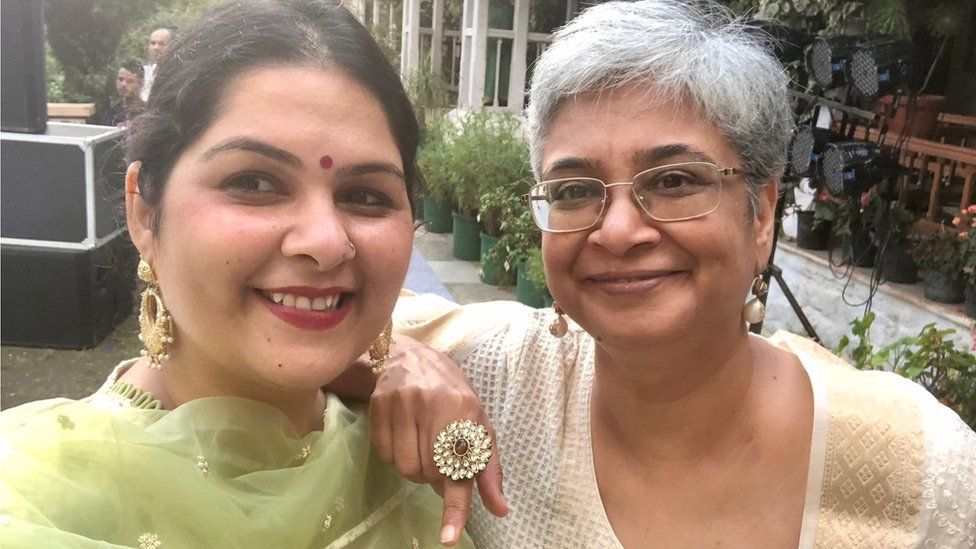

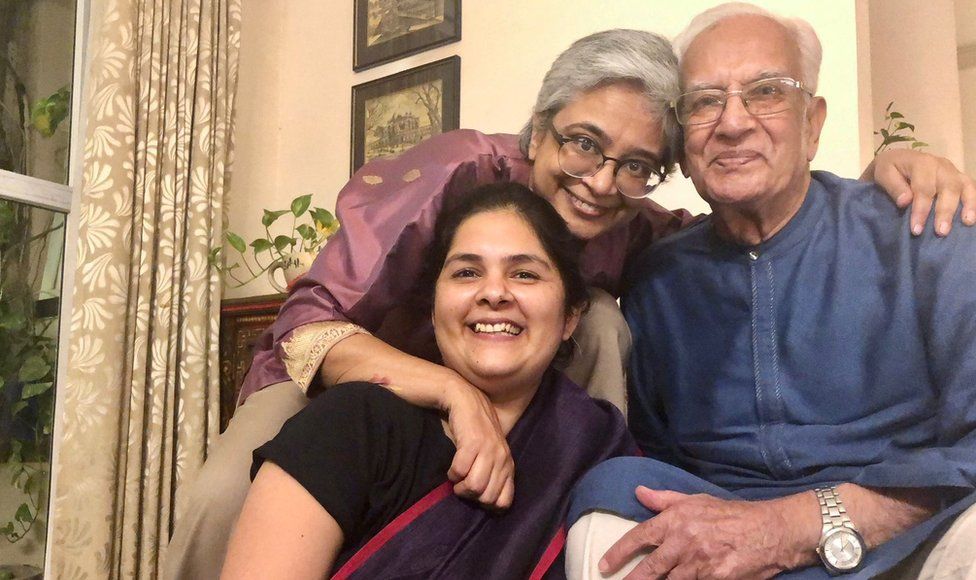

Among those keenly watching the proceedings would be Dr Kavita Arora and Ankita Khanna, a same sex couple who’ve been waiting for years to tie the knot.

For Kavita and Ankita, it wasn’t love at first sight. The women first became co-workers, then friends, and then came love.

Their families and friends readily accepted their relationship, but 17 years after they met and more than a decade after they started living together, the mental health professionals say they are unable to marry – “something most couples aspire to”.

The two are among nearly a dozen and a half couples who have petitioned the Supreme Court to allow same sex marriage in India. At least three of the petitions have been filed by couples who are raising children together.

Chief Justice DY Chandrachud has called it a matter of “seminal importance” and set up a five-judge constitutional bench – which deals with important questions of law – to rule on it.

The debate is important in a country which is home to an estimated tens of millions of LGBTQ+ people. In 2012, the Indian government put their population at 2.5 million, but calculations using global estimates believe it to be at least 10% of the entire population – or more than 135 million.

Over the years, acceptance of homosexuality has also grown in India. A Pew survey in 2020 had 37% people saying it should be accepted – an increase of 22% from 15% in 2014, the first time the question was asked in the country.

But despite the change, attitudes to sex and sexuality remain largely conservative and activists say most LGBTQ+ people are afraid to come out, even to their friends and family, and attacks on same sex couples routinely make headlines.

So a lot of attention is focussed on what happens in the top court in the coming days – a favourable decision will make India the 35th country in the world to legalise same sex union and set off momentous changes in society. A lot of other laws, such as those governing adoption, divorce and inheritance, will also have to be rejigged.

Ankita and Kavita say they hope it will happen, because that will make it possible for them to marry.

Ankita, a therapist, and Kavita, a psychiatrist, together run a clinic that works with children and young adults with mental health issues and learning disabilities.

On 23 September 2020, they applied to get married.

“We were at that stage in our relationship where we were thinking about marriage. Also, we were tired of fighting the system each time we wanted something done – such as get a joint bank account or a health insurance policy, own a house together, or write a will.”

One incident that proved “a catalyst” was when Ankita’s mother needed an emergency surgery but Kavita, who had accompanied her to the hospital, says she couldn’t sign the consent form “because I couldn’t say I was her daughter, nor could I say I was her daughter-in-law”.

But on 30 September, when they went to the magistrate’s office in their area, seeking to solemnise their marriage, they were turned away.

The couple then petitioned the Delhi high court, seeking legalisation of same sex marriage – and a direction to the authorities to register their wedding.

After a number of similar petitions were filed by same-sex couples in the Supreme Court and across high courts in India, the top court in January bunched them together and said it will deliberate the “important” issue.

In their petition, filed through senior lawyer Menaka Guruswamy, Ankita and Kavita say “what we seek is not the right to be left alone, but the right to be acknowledged as equals.”

The Indian constitution, their petition adds, gives all citizens the right to marry a person of their choice and prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and their petition should be allowed since “constitutional morality is above social morality”.

“I’m very optimistic and have great faith in the judiciary,” Ms Guruswamy, whose team is representing six same-sex union cases in court, told the BBC.

Some of her optimism come from reading the December 2018 judgement that decriminalised gay sex – “the thing that struck me most was that the court emphasised the right to choice of partner and that makes me very optimistic”, she said.

While striking down the colonial-era law, the judges also said that “history owed an apology to LGBT people and their families for the ignominy and ostracism they have faced”.

But considering the opposition to same sex marriage from the government and religious leaders, Ms Guruswamy has a tough fight on her hands.

The Indian government has urged the top court to reject the petitions, saying that a marriage could take place only between a man and a woman who are heterosexual.

“Living together as partners and sexual relationships by same sex individuals … are not comparable with the Indian family unit concept of a husband, a wife and children,” the law ministry argued in a filing in the court.

It added that the court cannot be asked “to change the entire legislative policy of the country deeply embedded in religious and societal norms” and that matter should be left to be debated in the parliament.

In a rare show of unity, leaders from all of India’s main religions – Hindu, Muslim, Jain, Sikh and Christian – also opposed same sex union, with several of them insisting that marriage “is for procreation, not recreation”.

And last month, 21 retired high court judges also weighed in on the subject. Legalisation of same-sex marriage would have a “devastating impact on children, family and society”, they wrote in an open letter.

The judges added that allowing same-sex marriage could increase incidence of HIV-Aids in India and expressed concern that it could “negatively affect the psychological and emotional development of children raised by same-sex couples”.

But last weekend, the petitioners received a major boost when Indian Psychiatric Society (IPS) – the country’s leading mental health group which represents more than 7,000 psychiatrists – issued a statement in their support.

“Homosexuality is not a disease,” the IPS said in a statement, adding that discrimination against LGBTQ+ people could “lead to mental health issues in them”.

The IPS statement carries some heft – in 2018, the organisation had released a similar statement supporting decriminalising gay sex and the Supreme Court had referred to it in their judgement.

I ask Ankita and Kavita what they think will happen in court?

“We know that the constitution was framed to allow for equality and diversity and our faith in judiciary and constitution is unwavering,” says Ankita.

Adds Kavita: “We knew there would be opposition, we knew this wasn’t going to be a cakewalk. But we chose to undertake this journey, this is what we started, let’s see where it takes us.”

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC: