As rare earths from Myanmar travel around the world, they pass through many hands.

The most destructive mining is for heavy rare earths, which are critical to make powerful magnets heat-resistant. Ores are trucked across the border from illicit mines in Myanmar to southern China, where state-owned companies buy them up in sacks by the thousands. Among them: Minmetals, China Southern Rare Earth, and Rising Nonferrous Metals.

Some 70 per cent of China Southern’s rare earth ores came from Myanmar, with the rest from recycling, Jiangxi customs official Liu Jingjing wrote in a paper. China Southern, among the world’s largest processors of heavy rare earths, has no active mining in China, according to Liu’s paper. A company post highlighted how it is “seizing overseas rare earth resources” and “opening up” imports from Myanmar.

Minmetals, another major producer, warned shareholders in recent annual reports that it relied heavily on imports, as its one major mining project in China didn’t produce enough. Rising Nonferrous, the third company, wrote on their website in 2020 that their trading subsidiary had won approval from Chinese customs to import Myanmar heavy rare earth ores.

All three companies did not respond to calls, emails and faxes requesting comment.

Those companies in turn supply three major magnet companies: Yantai Zhenghai Magnetic Material, JL MAG, and Zhong Ke San Huan, public agreements show. Rising Nonferrous also supplies Guangdong TDK, a joint venture with Tokyo-based TDK, one of the world’s largest manufacturers of cell phone, laptop, and hard drive components and a supplier of Apple and Samsung. TDK and the magnet companies did not respond to requests for comment.

As the ore is transformed into magnets, it is separated, refined and melted, according to interviews with miners and magnet engineers. Along the way, materials from different sources often get mixed, making it difficult to track any particular shipment of rare earths from Myanmar to a specific batch of magnets.

Chinese magnet makers often don’t know where their rare earths come from because many multinational companies don’t ask, an engineer at one company noted.

“There’s never been like, where do you get your rare earth?” said the engineer, declining to be named to speak candidly. “There should be concern, but there’s no concern within the industry.”

The magnet companies go on to supply intermediaries like components manufacturers and trading companies as well as big brands. The rare earths can pass through many more tiers of suppliers before reaching a consumer.

“The transparency in this industry is just so poor that the companies don’t know,” said Kristin Vekasi, a professor studying rare earth sourcing at the University of Maine.

Among global carmakers, GM, Volkswagen, and Mercedes said they expect suppliers to adhere to codes of conduct and due diligence, and Mercedes added that they were designing new motors to eliminate heavy rare earths. Ford said they conduct audits and request suppliers to identify sourcing.

Hyundai denied using rare earths from Myanmar, and Stellantis said that “to the best of Stellantis’ knowledge”, their rare earth supply chains only involve operations in China. Some auto parts makers, including Bosch, Brose and Nidec, also said they were assured by the magnet companies that their components were free of rare earths from Myanmar. Others, such as Continental AG and BorgWarner, said they expected suppliers to adhere to their codes of conduct.

However, only an order from the Chinese government could force companies to separate rare earths from Myanmar and China, according to Nabeel Mancheri, secretary general of the Rare Earth Industry Association. The group is trying to build a blockchain-based verification to link up international customers with the Chinese companies “upstream”.

“Nothing exists on auditing the Chinese supply chain,” he said. “Downstream players simply rely on whatever certificate they get from Chinese companies.”

Among electronics giants, Samsung said they did not tolerate rights violations or environmental damage but did not answer other specific questions about their suppliers. Toshiba, Panasonic and Hitachi did not comment on suppliers but said they would suspend working with businesses violating human rights.

Thyssenkrupp said it had “initiated measures” to find out more about the origin of the minerals for its magnet supplier. Other machinery manufacturers like Mitsubishi did not respond.

Among wind turbine manufacturers, Siemens Gamesa, which has projects in the United State and Europe, said it audits immediate suppliers and is preparing to trace those further upstream. It said “supplier feedbacks” showed only rare earths from China. Other wind companies, like Xinjiang Goldwind, did not respond.

But Klinger, the expert on illicit minerals tracing, said the only way for a company to be certain to avoid rare earths from Myanmar is to have their supply chain “entirely outside of Myanmar, China and potentially outside Southeast Asia”. She said there are cleaner ways to mine, but they cost more – a huge hurdle in the cutthroat world of commodities.

Mike Coffman, a congressman who pushed for the original US conflict minerals rules a decade ago, said he would like to see an expansion of the domestic supply of rare earths minerals, which is now before Congress. And US Senator John Cornyn, a Texas Republican, introduced a measure this year aimed at reducing US reliance on China for rare earths and other critical minerals.

However, alternatives are still a long way in the future. In 2022, the US and Australian governments both backed domestic rare earths projects with multimillion dollar financing, but facilities are years and tons of metals behind China’s current capacity.

Other countries with rare earths deposits are reluctant to mine them. Greenland’s parliament last year voted to halt a rare earth mining project, and efforts to develop a promising deposit in Sweden stalled because of local objections.

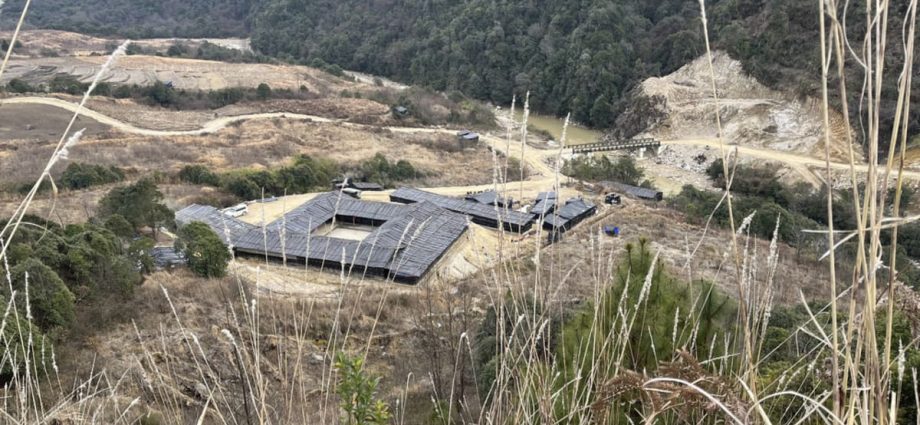

In the meantime, villagers still protest in one area in northern Myanmar where the black cardamom and walnuts grow – for now. Standing in the green mountains under a tree, a villager made it clear why they continue to raise their voices even when there’s been no recourse for others just a few mountains away.

“They are mining rare earth everywhere and we are no longer safe to drink water,” she said. “There is nothing to support the children. Nothing to eat.”