NASA’s DART-game victory hasn’t gotten the attention or respect it deserves.

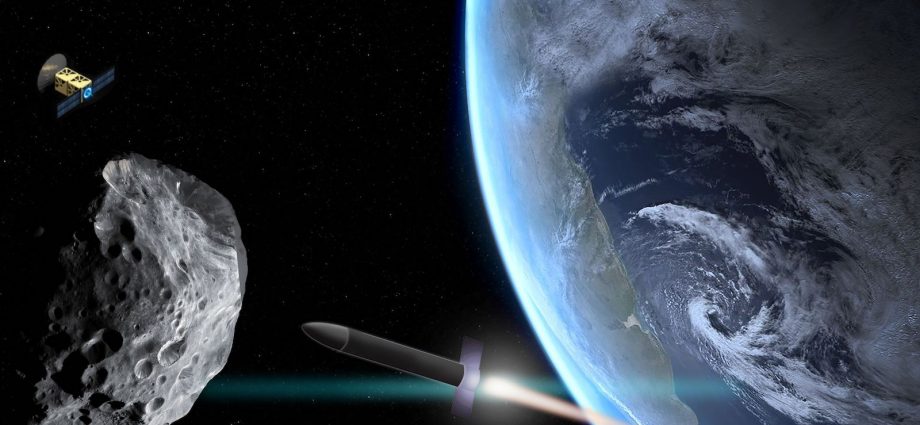

Even the news media reports on the agency’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test have been fragmentary. On September 26 the media weighed in on NASA’s successful crashing of a golf-cart-sized spacecraft into an asteroid. News organizations also covered NASA’s October 11 announcement that the crash had achieved its goal of knocking the asteroid off course.

But that’s it. So far, this story has been a two-day wonder. It hasn’t been treated as an event whose implications deserve further exploration. Pundits haven’t been opining about its meaning.

That seems strange because this feat is arguably as important as the 1969 landing of a man on the moon. Not to take away anything from that historic NASA achievement, but the moon poses no threat to anyone on earth, save for the occasional rip tide. Asteroids pose threats.

The six-mile-wide Chicxulub Asteroid that hit the Yucatan Peninsula 65 million years ago wiped out 70% of all species on earth, including the dinosaurs. In 2013, an asteroid exploded over the Russian city of Chelyabinsk, creating a shockwave that injured 1,500 people and destroyed 7,200 buildings across six cities.

Being able to stop one of these babies from reaching earth is huge.

The moon landing prompted some major philosophizing in the media. I remember it well. As the greenest of greenhorn reporters at the Wall Street Journal, just two months out of college, I was assigned to make phone calls to philosophers around the world, asking them to hold forth on the event’s meaning. And hold forth they did. Where are the philosophers holding forth about DART?

What astronaut Neil Armstrong said when he touched down on the moon – “That was one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” – captured people’s imaginations. The same can’t be said, alas, for NASA administrator Bill Nelson’s October 11 declaration that knocking the asteroid off course was “a watershed moment for planetary defense and a watershed moment for humanity.”

Yet he was right. The ability to ward off an asteroid strike is potentially life-changing for earth and its inhabitants. The success of this audacious and in some ways outlandish mission also reminds us not to give up on bold new technological solutions to big problems. As balance to my recent column that called solving climate change “the techno-optimist’s dilemma,” I’m willing to concede that DART looks like a techno-optimist’s triumph.

There are, to be sure, reasons why DART has been underappreciated. Speciesism –our human tendency to be especially interested in what others of our human species do – is part of it. We naturally find what a man does in space more gripping than what a machine does.

It’s also true that the end of a story is more satisfying than the beginning. What NASA achieved in 1969 was the fulfillment of a promise, President John F Kennedy’s 1962 vow to put a man on the moon by the end of the decade. What NASA achieved with DART is just the start of something. For the planet to be truly safe from asteroid strikes, much still needs to be done.

After all, this was just a test. Dimorphos, the asteroid DART knocked off course, wasn’t headed for earth. It was only 525 feet in diameter, less than 2% the width of the asteroid that did in the dinosaurs.

Still, it was big enough to cause billions in damage and take countless lives had it somehow struck the earth. The spacecraft that hit Dimorphos, which was going 14,000 miles per hour, shortened the asteroid’s orbit time around another asteroid, Didymos, by 32 minutes or about 4%. That looks like enough to have prevented a strike had Dimorphos been headed our way.

Years of observation of Dimorphos lie ahead. There’s a lot to be learned yet about the effects of this crash.

Scientists will also look at whether there’s a more effective way of targeting asteroids than crashing a spacecraft into them. One idea is shooting ion beams at them.

Perhaps the most important to-do is the hoped-for 2028 launch into space of a special telescope. It will provide far more information about earth-threatening asteroids and allow far more time to work on missions to combat them.

And then there’s the inevitable international dialogue. If the goal of this device is to protect the planet, the rest of the planet will likely want to have a say in its use. That’s especially likely if it turns out there are unanticipated consequences to knocking asteroids off course.

Don’t be surprised if the project has its detractors. Some will object to tampering with the movement of celestial bodies. It’s too dangerous, they’ll say; let nature take its course.

But homo sapiens is part of nature and it’s in our species’ nature to tamper with nature. We’ve been doing it for millennia, changing the course of rivers, breeding plants, domesticating animals, rearranging genomes.

Not everything that can be done should be done, to be sure. But just as every action has consequences, intended and unintended, so does every inaction. Technologies that can save large numbers of lives shouldn’t be ruled out simply because they seem like unnatural exercises of godlike powers.

Let’s give DART the attention and respect it deserves.

Former longtime Wall Street Journal Asia correspondent and editor Urban Lehner is editor emeritus of DTN/The Progressive Farmer. This article, originally published on November 1 by the latter news organization and now republished by Asia Times with permission, is © Copyright 2022 DTN/The Progressive Farmer. All rights reserved.

Follow Urban Lehner on Twitter: @urbanize