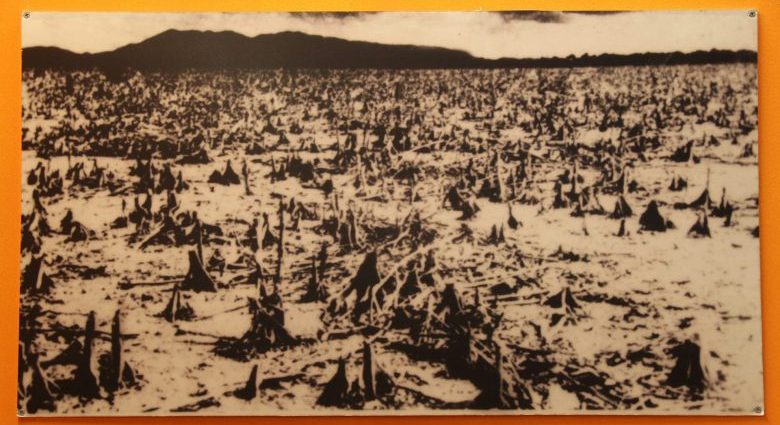

When the Vietnam War came to an end on April 30, 1975, it left behind a surroundings ruined by economic damage. Great stretches of coastal trees, when housing rich companies of fish and birds, lay in ruins. Trees that had lots of species on display were reduced to dried-out fragments and overgrown with aggressive grasses.

In the late 1960s, the term “ecocide” was coined to describe the US government’s use of pesticides like Agent Orange and burning weaponry like napalm to combat insurgent forces that used jungles and marshes as hiding places.

Fifty years later, Vietnam’s degraded communities and dioxin-contaminated grounds and waters also reflect the long-term natural outcomes of the battle. There have been little effort to repair these damaged landscapes or even examine the long-term effects.

As an ecological scientist and archaeologist who has been in Vietnam since the 1990s, I find the lack of attention and delayed healing work to be deeply disturbing. Although the battle spurred new international agreements aimed at protecting the environment during war, these attempts failed to convince post-war recovery for Vietnam.

These laws and treaties are also ineffective, despite the current conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East.

Daisy scissors and Agent Orange

The US second sent floor troops to Vietnam in March 1965 to help South Vietnam against revolution troops and North Vietnamese army, but the battle had been going on for years before then. The U.S. government turned to climate adaptation technologies to combat an obscure foe that was operating covertly at night and from hideouts strong in swamps and jungles.

Operation Ranch Hand, the most well-known of these, sprayed at least 19 million gallons ( 75 million liters ) of herbicides over South Vietnam’s 6.64 million acres ( 2.66 million hectares ).

The chemicals fell on forests, and also on rivers, rice paddies and villages, exposing civilians and troops. More than half of that spraying involved the Agent Orange, a defoliant, that was contaminated with dioxin.

Herbicides were used to remove leaf cover from forests, improve visibility along transportation routes, and obliterate crops suspected of providing guerrilla forces.

Scientists contacted President Lyndon Johnson about the campaign’s environmental effects and demanded a review of whether the US was using chemical weapons on purpose as soon as news of the damage from these tactics returned to the US. American military leaders ‘ position was that herbicides did not constitute chemical weapons under the Geneva Protocol, which the US had yet to ratify.

During the war, scientific organizations conducted research in Vietnam that discovered widespread destruction of mangroves, the loss of rubber and timber plantations, and the harm to lakes and waterways.

Due to the presence of TCDD, a particularly harmful dioxin, in Agent Orange, 2, 4, 5, and 5, one study in 1969 established a link between the chemicals. That led to a ban on domestic use and suspension of Agent Orange use by the military in April 1970, with the last mission flown in early 1971.

Rich ecosystems in Vietnam were also ravaged by incurable weapons and the clearing of forests.

By igniting barrels of fuel oil that were dropped from aircraft, the US Forest Service tested large-scale incineration of jungles. Particularly feared by civilians was the use of napalm bombs, with more than 400, 000 tons of the thickened petroleum used during the war. Invasive grasses frequently took over in hardened, infertile soils following these infernos.

1, 000 acres of land could be cleared each day using” Rome Plows,” massive bulldozers with an armor-fortified cutting blade. Enormous concussive bombs, known as “daisy cutters,” flatten forests and erupt shock waves that kill everything within a 3, 000-foot (900-meter ) radius, right down to earthworms in the soil.

The US also engaged in weather modification through Project Popeye, a secret program from 1967 to 1972 that seeded clouds with silver iodide to prolong the monsoon season in an attempt to cut the flow of fighters and supplies coming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail from North Vietnam.

In 1973, Congress finally passed a bipartisan resolution urging an international treaty to outlaw the use of weather modification as a means of war. That agreement became effective in 1978.

The US military contended that all these tactics were operationally successful as a trade of trees for American lives.

Despite the concerns of Congress, little was done to examine the effects of US military operations and technologies on the environment. There was no regular environmental monitoring, and research sites were difficult to access.

Recovery efforts have been slow

The US imposed a trade and economic embargo on all of Vietnam after Saigon was overthrown by North Vietnamese troops on April 30, 1975, leaving the nation both war-damaged and cash-strapped.

Vietnamese researchers described how they assembled small-scale studies. One found a dramatic drop in bird and mammal diversity in forests. By the early 1980s, 80 % of the forests in the A Li valley in central Vietnam had not recovered from herbicide exposure. In those areas, biologists discovered only 24 bird and five mammal species, which is significantly below what is expected for unsprayed forests.

Only a handful of ecosystem restoration projects were attempted, hampered by shoestring budgets. The most notable project started in 1978 when foresters began hand-planting mangroves near the Saigon River in Cn Gi forest, which had been completely destroyed.

In inland areas, widespread tree-planting initiatives in the late 1980s and 1990s finally took root, but they focused on planting exotic trees like acacia, which did not restore the original diversity of the natural forests.

Chemical cleanup is still being done.

For years, the US also denied responsibility for Agent Orange cleanup, despite the recognition of dioxin-associated illnesses among US veterans and testing that revealed continuing dioxin exposure among potentially tens of thousands of Vietnamese.

After persistent advocacy by veterans, scientists, and nongovernmental organizations led Congress to authorize US$ 3 million for the restoration of the Da Nang airport, the first remediation agreement between the two nations only came into existence in 2006.

The 150 000 cubic meters of dioxin-laden soil was treated in that project, which was finished in 2018, for an estimated cost of more than$ 115 million, mostly funded by the US Agency for International Development, or USAID. The cleanup required lakes to be drained and contaminated soil, which had seeped more than 9 feet ( 3 meters ) deeper than expected, to be piled and heated to break down the dioxin molecules.

Another significant hotspot is the contaminated Biên Hoà airbase, where local residents continue to consume high levels of dioxin through fish, chicken, and ducks.

Agent Orange barrels were kept at the base, which caused significant contamination to the soil and water as it moved up the food chain. It still accumulated in animal tissue as it continues to contaminate animal tissue.

Remediation began in 2019, however, further work is at risk with the Trump administration’s near elimination of USAID, leaving it unclear if there will be any American experts in Vietnam in charge of administering this complex project.

The laws preventing a future “ecocide” are complex.

While Agent Orange’s health effects have understandably drawn scrutiny, its long-term ecological consequences have not been well studied.

In addition to satellite imagery, which is being used in Ukraine to identify fires, flooding, and pollution, there are far more options available to scientists today than they did fifty years ago. These tools, however, cannot replace ground monitoring, which is frequently restricted or dangerous during conflicts.

The legal situation is similarly complex.

The Geneva Conventions for conduct during wartime were revised in 1977 to make it illegal to “widespread, long term, and severe damage to the natural environment.” Incendiary weapons were restricted by a 1980 protocol.

Yet oil fires set by Iraq during the Gulf War in 1991, and recent environmental damage in the Gaza Strip, Ukraine and Syria indicate the limits of relying on treaties when there are no strong mechanisms to ensure compliance.

An international campaign currently underway calls for an amendment to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court to add ecocide as a fifth prosecutable crime alongside genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and aggression.

Some nations have adopted their own ecocide laws. Vietnam was the first country to legally state in its penal code that “ecocide, destroying the natural environment, whether committed in time of peace or war, constitutes a crime against humanity.” Yet the law has resulted in no prosecutions, despite several large pollution cases.

Both Russia and Ukraine have ecocide laws, but neither have they prevented harm or held anyone accountable for harm during the ongoing conflict.

The Vietnam War serves as a reminder that failing to take into account environmental effects, both during and after the war, will have long-term effects. What remains in short supply is the political will to ensure that these impacts are neither ignored nor repeated.

Rutgers University professor of human ecology, Pamela McElwee

This article was republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.