Reuters

ReutersPeople working in hospitals in Pakistan say they frequently face physical abuse, violence and verbal misuse, from adult colleagues, patients and their families.

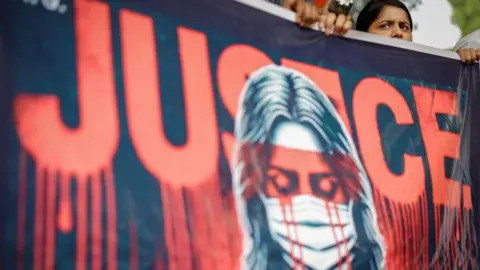

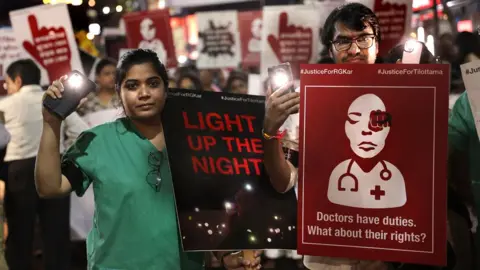

Following the rape and murder of a 31-year-old trainee doctor at work in an Indian hospital, more than a dozen female medics in Pakistan told the BBC they were worried about their own safety.

However, this is largely undiscovered because many people are too afraid to report crimes, while those who do are frequently told that no one will assume their claims.

The majority of the people we spoke to asked for anonymity out of respect for their “honor and respect ” in order to avoid losing their jobs.

A few months ago, a fresh physician came to Dr Nusrat ( not her real name ) in tears. A female physician had filmed the person through a hole in the wall while she was using the restroom and was using the footage to slander her.

“ I suggested filing a complaint with the FIA [ Federal Investigation Agency, which handles cyber crimes], but she refused. She stated that she did n’t want it to be leaked and reach her family or in-laws. Dr. Nusrat also mentioned that she is aware of at least three other instances where female doctors have been covertly filmed.

Dr. Nusrat just so happened to know a senior police officer who had spoken to the fraudster and warned him that he might face arrest for what he had done. The police agent ensured that the picture was removed.

“ Unfortunately, we could n’t take further action, but we got the hole covered so that no-one could do it again, ” says Dr Nusrat.

Different women shared their sexually harassing activities, including Dr. Aamna ( not her real name ), who was a native health officer in a state medical five years ago when she was targeted by her potent top doctor.

“ When he saw me with a folder in my side, he may try to bend over it, create inappropriate comments, and try to touch me, ” she says.

She filed a complaint with the doctor administration, but says she was met with indifference. I was informed that I had only been there for a short while, and I was asked what evidence I had of this abuse. They said,’ We’ve been unable to resolve this man in seven decades- nothing will change, and no-one did feel you’. ”

Dr. Aamna claims she is aware of different people who have managed to capture videos of intimidation, but little happens: the harasser is simply moved to another hospital for a few months before returning.

She had to finish her position before she could become a doctor, but she made the move right away.

Her history is alarmingly prevalent, according to evidence gathered by the BBC.

The root of the problem lies in a lack of trust and accountability, according to Dr Summaya Tariq Syed, the chief officers doctors in Karachi and nose of Pakistan’s second rape crisis center.

She claims she has been disappointed with how things are handled and that her 25 years of service have been a constant struggle against violence and deception.

She relates how, a few years back, when she was working in a distinct role, coworkers wanted her to alter what she had written in a post-mortem assessment report about a deceased person.

“They said, ‘Sign it or you have no idea what we’ll do to you’, ” but she refused. Given the top position of one of the persons involved, she says, no action was taken against them.

Another female physician at a Punjabi state hospital explains how difficult it can be for women to document abuse.

“The [hospital ] committees that do exist often include the same doctors who harass us, or their friends. So why would someone lodge a grievance and make things even more difficult for them? ”

No formal data is available about the attack against Pakistani female health workers. However, a review in the US National Institutes of Health in 2022 creates a disturbing picture. According to the survey, 95 % of Pakistani nurses have experienced working crime at least once during their careers. This includes abuse and risks as well as verbal and emotional abuse, from acquaintances, patients and medical visitors.

This contrasts favorably with a record in the Pakistan Journal of Medicine and Dentistry that estimates a 2016 study of Lahore’s public hospitals, which suggested 27 % of midwives had experienced physical violence. Additionally, it cites a study from Pakistan’s north-western Khyber Pakhtunkha province, which found that 52 % of female doctors and 69 % of nurses there had experienced some form of sexual harassment from other staff members.

A doctor at a government hospital lured a caregiver to his dormitory, where he was n’t alone; there were two other doctors there as well, according to Dr. Syed, in Karachi in 2010. The caregiver was raped, and she jumped off the roof, where she was a coma for about a fortnight. She was so upset. “Nothing that happened was lawful. But she made the decision to ignore the situation. ”

Dr. Syed believes that patients are frequently blamed in world, and that if the nurse had reported it,” the blame would had fallen on her.”

She claims that patients, their friends, and families also suffer harassment and threats from her staff when they handled bodies in the mortuary next year. She cites instances of victims of public abuse.

Two people were forced to defend themselves from blows from a victim of attempted murder because I had warned him never to record video. ”

She filed a complaint with the officers, and she is currently awaiting the outcome of the legal process. Staying silent will only reinforce the perpetrators, according to the statement. ”

Another female doctors likewise describe a lack of safety as a problem, particularly in state-run facilities, where they say people can walk in unchecked. At least three claimed that the attackers were regular folks who had a drink-intention history. Alcohol consumption is generally prohibited in Pakistan.

According to Dr. Saadia ( not her real name ), some of her coworkers at a significant state hospital in Karachi have been subjected to numerous sexual harassment allegations. “It’s often people under the influence of drugs wandering into the doctor, ” she says.

A drunken person started harassing a coworker one evening as she was heading to another hospital. Another day, a distinct dentist was attacked. There were no safety personnel present, but some other physicians managed to remove the patient. ”

According to nurse Elizabeth Thomas, it’s common for drunken patients to try to reach them. “We feel terrified, uncertain whether to treat the person or defend ourselves. We feel absolutely vulnerable. Additionally, there is no safety personnel available to assist us. ”

According to Dr. Saadia, they are unsure whether someone who is sweeping the floor or posing as a patient on the street is truly staff.

Looking back at her time at a state hospital in Punjab five years ago, Dr Aamna says: “ In rural areas, forget about protection; they don’t perhaps have appropriate lighting in the corridors. ”

There are 1,284 state institutions in the country, according to the Pakistan Economic Survey 2023. Physicians claim that safety measures are exceedingly inadequate.

According to healthcare professionals, many either lack CCTV cameras or have too few, and those that do frequently do n’t work as intended. They claim that attacks on health workers have become a common practice because thousands of patients and their families visit these facilities every day.

Dr. Saadia describes how she once had to cover after a victim’s equivalent attacked her because she waited for the results to appear before giving an treatment.

He yelled at me as he approached him because he was high. I was forced to close the entrance. He threatened me, saying, ‘Give the injection then, or I’ll remove you’. ”

Some of Pakistan’s care workers come from majority non-Muslim areas, which can make them susceptible in other way, says Elizabeth Thomas.

“ I know some midwives who are harassed, and if they don’t agree, they’re threatened with accusations of heresy. If a caregiver is beautiful, they’re usually told to change their faith.

We are always left wondering how to respond because they might falsely accuse us of blasphemy if we do n’t do what they want. This has happened to caregivers. ”

On top of the misuse, female specialists describe enduring much, demanding swings with a lack of simple services.

“During my home work, we went through days when, during a 30-hour move, we did n’t possess a place to sleep in. We would go outside and rest in a colleague’s vehicles for 15 days or so, ” says Dr Saadia.

“ When I was in the disaster hospital, there was no bathroom. We had n’t go to the washroom during 14-hour transitions. Even when we were bleeding, we had n’t apply a toilet. ”

She claims that hospital staff did n’t have time to use the restrooms because they were located in other blocks.

EPA

EPAThe BBC contacted the local health officials in the four provinces where these women have made comments, as well as the Lahore regional health coordinator, but they were unsuccessful in responding.

Since the apprentice physician was raped and killed in India, female doctors in Pakistan have been debating ways to ensure their own safety.

Dr. Saadia claims that it has had a profound impact on her and that her program has changed: “ I no longer go to dark or lonely places. I used to take the stairs, but then I feel safer using the weights. ”

Elizabeth Thomas claims that it has also shaken her. “ I have a seven-year-old girl, and she often says she wants to become a dentist. But I keep wondering, is a doctor protected in this state? ”