ABC News/Luke Bowden

ABC News/Luke BowdenFor weeks, an unexpected statue sat in an oak-lined circle at the heart of Tasmania’s funds: a pair of severed metal feet.

For more than a century, a monument of renowned surgeon-turned-premier William Crowther had hung over the garden in Hobart. However, one May evening, it was severely damaged and had the words “what goes around” written on its rock bottom.

A morgue was reportedly broken into by Crowther, sliced opened an Indian president’s head, and stole his bone, causing a terrible struggle over the remaining body parts.

Tasmania was the center of coloniser attempts to obliterate Tribal people in Australia. Additionally, William Lanne, the soldier on the block, was hailed as the last person to arrive on the island, making his remains a bizarre trophy for white doctors.

Some view Crowther as a badly anti-American man of his day and his image as a significant portion of the government’s history, warts and all.

But for Lanne’s heirs, it represents imperial brutality, the dehumanising misconception that Tasmanian Aboriginal individuals are dead, and the scapegoating of the island’s history.

Tribal activist Nala Mansell says,” You walk around the city everywhere and you’d never realize Aborigines were here.”

The dismembered monument has now evolved into a symbol of a town and a country struggling to cope with its darkest chapters.

The death stay

Some sites capture the problem really like Risdon Cove, which the Palawa Aboriginal people refer to as piyura kitina.

A monument happily commemorates it as the first English colony to exist on what was then known as Van Diemen’s Land, nestled next to a creek.

BBC/Andrew Wilson

BBC/Andrew WilsonFor Australian Aboriginal individuals, though, this mountain on the outskirts of Hobart is “ground no for conquest”.

” It’s the first landing and not coincidentally the first massacre]of our people ]”, Nunami Sculthorpe-Green tells the BBC one overcast day.

Startled from their trance, local hen flakes, which piyura kitina is named after, sprinkle over the lush grass as we arrive.

A marsupial hurriedly travels towards limited candy trees. On May 3, 1804, the Mumirimina people, women, and children may have climbed the mountain and sung while they were kangaroo hunters.

They were met with muskets and guns.

The occurrences of that day- and the dying burden- are disputed. What is uncontested is that this marked the start of a determined campaign by English settlers to eradicate the initial Tasmanians, nine countries with up to 15 000 inhabitants.

Tribal citizens were hunted across the island during the war, and the victims were taken captive and transported to what have been referred to as death camps.

” If that happened anywhere in the world today, it would be referred to as cultural cleansing”, says Greg Lehman, a Palawa professor of history.

This article contains pictures of someone who has passed, so be warned to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

Lanne, who was kidnapped as a child, spent her last years living in his native land and serving as a favorite argue for his people.

Letters reveal that strong Hobartians had begun plotting even before he passed away from illness in 1869 at the age of 34.

There is no way that that young gentleman would be permitted to stay in a tomb. No way”, writer Cassandra Pybus tells the BBC.

She claims that the fraud of Aboriginal remains had long been tolerated, but in Tasmania, the number of unique citizens had slowed.

Lanne’s skull was used to refute long-since discredited theories about Tasmanian Aboriginal people, claiming that they were the only connection between people and Neanderthals, a distinct race so primitive that they did n’t even know how to make fire.

Before he was buried, his hands and feet would also be cut off and pocketed by surgeons. According to some researchers, his tomb was also robbed, and every bone in his body was removed.

Crowther never denied having part in the theft of Lanne’s bones; his supporters called the allegations a monster chase, but the city was horrified, and he was suspended from his honourable place at the doctor.

What transpired was particularly upsetting for First Countries people, who feared their spirits would just rest when they returned to their property.

But within two weeks, Crowther was elected to state legislature, and he’d quickly rise to become Tasmania’s top for an ordinary six months.

By comparison, Lanne’s bones appears to have wound up on the other side of the world at a UK college, and his people were quickly declared dead.

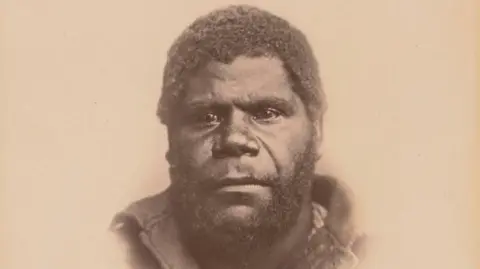

National Library of Australia/J. W. Beattie

National Library of Australia/J. W. BeattieExcept they were no.

While different groups, which some do not recognize as Aboriginal, claim their heritage is the work of a few women who managed to avoid being captured in the 1800s, Palawa people today claim their lineage is the product of a dozen women who survived.

However, for the past 150 years, Australian Aboriginal people say they have been fighting to get obvious, in the background pages and in everyday living.

The myth that they are dead is largely attributable to outdated perceptions of ethnic identity. Others claim that it was also a strategic decision to refuse Aboriginal people in Tasmania the rights and powder out their lifestyle.

The effect has been devastating. Some Palawa people claim to have been targeted for their Native American blood in one incident but denied their identity because of their white lineage the following.

Some people still believe that significant portions of their past have been lost or purposefully ignored.

Nala points out that her Hobart school’s only brief instruction in Australian Aboriginal culture and history was in the form of a short lesson on boomerangs and didgeridoos, despite the fact that neither of her people used either.

There are no sites in the area that honor Indian people, aside from a walking trail named after Lanne’s wife and a head in her own right named after her.

According to Nunami,” The way they tell stories about Indian people… they want you to believe that it’s there very far away from where you are, and that it’s anything that happened a very long time ago.”

Unimpressed, the 30-year-old past student started Black Led Tours to fill the gap.

Black Led Tours Tasmania/Jillian Mundy

Black Led Tours Tasmania/Jillian Mundy” I realized that I was going to work in the same manner as Truganini used to lead her canines.” And I discovered that my kids had a drinking zoo at William Lanne’s death bed. Additionally, I learned that the Crowther memorial was right next to my vehicle stop.

” And I thought: does anyone know that this is straight below, where we live and where we work?”

A disputed tradition

When unveiling the image in 1889, the then-premier said Crowther was no” a great man”, but one who spent his time doing fine.

His incident was overlooked, but he was most famous for providing poor people with free health care until late.

That rankles Australian Indian people like Nala:” It’s merely a push in the guts.”

She spearheaded a new effort to remove the commemoration as the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre’s representative.

She says,” Having a memorial of Martin Bryant would be no different from having a memorial of him,” referring to the shooter who massacred 35 people in near Port Arthur in 1996.

However, some people, such as Jeff Briscoe, who lost the situation to stop the figure’s removal, think the sculpture has magnificent heritage value because it is the only state memorial that is “fundamentally funded by the public.”

It was a major monument at the time, and everyone was pleased with it. If a couple people’s views rule the world in 2024?

” It’s not as though he was shooting people; he might have been involved in a body’s amputation, but they all were.”

No imperial monument will be protected in Australia because they are lowering the bar so low.

BBC/Andrew Wilson

BBC/Andrew WilsonCassandra Pybus claims there is no denying that Crowther mutilated Lanne, citing letters he wrote. Yet, she had argued, like Mr Briscoe, that taking down the monument had set a dangerous law, because” everybody was prejudiced”.

She desired it to continue so that the website could be used to inform visitors about the treatment of the primary Tasmanians.

The monument’s fate divided also Crowther’s living heirs, with some officially supporting the calls for elimination, and others frightened by them.

The committee voted to reduce the monument in 2022, according to Hobart Lord Mayor Anna Reynolds, as a” devotion to telling the truth about our city’s record and as an act of peace with the Indian community.” This is the first of its kind in Australia.

They did it after a thorough assessment and with the help of the” passive majority”, she adds.

Ultimately, she says, the statue is a sign of how desperate Crowther was to repair his reputation, not his significance to the state: “] He’s ] not that important.”

Some became restless and imposed red tape themselves while the government worked through it.

ABC News/Luke Bowden

ABC News/Luke BowdenFor Lanne’s successors, their pleasure at the long-awaited collapse of the statue is tinged with pain. They believe that Lanne has been reduced to his demise.

” He had a whole life… and just as he advocated for our women’s rights, we will advocate for his story to be remembered and him to be respected for who he was,” Nunami says.

Time for’ truth-telling’?

The Crowther monument is hardly unique. There are still numerous other identical monuments or monuments across Australia that joke about massacres, use racist slurs, or honor alleged murderers.

Some, like Greg, believe removing or renaming them could be a natural starting point for the” truth-telling” the land needs, to balance with its First Peoples, the oldest living society on the planet.

” You’d believe that it was just a bunch of happy completely inhabitants and not-so-happy prisoners who jumped off the First Fleet… and bingo, there you’ve got present Australia, “he says.

Australia must have an honest partnership with the past in order for it to have an honest and strong relationship with itself.

But after a proposal for an Indigenous political advisory body was defeated at a referendum last year, any movement towards a national truth-telling inquiry has stalled – though many states are setting up their own.

A” truth-telling” process would be a controversial and unnecessary repeating of the past, views that a group of liberal politicians who also oppose a agreement still hold.

Folks want Aborigines to greet them in front of them and allowed us to our nation today. They request that we dance for them. They want us to tell them our speech. They do n’t mind if we put some of our paintings in the mall,” Nala says.

” But if you talk about … any type of profit for the Indian area, or taking up anything that was stolen from us, it’s a completely different ballgame.”

Nevertheless, she appears to be a part of the tide’s gradual turning.

” The Crowther statue … is the first moment I’ve always thought,’ Wow, white folks- they’re starting to get it’,” Nala says.

Blak Led Tours Tasmania/Jillian Mundy

Blak Led Tours Tasmania/Jillian MundyWhen the sculpture met its sudden end, the council was nevertheless deciding what to replace it with.

But some wanted the severed feet to stay in the square- as is- arguing they made a sardonic” interesting “and” serious” statement.

However earlier this week, the council plucked the ankles from their perch, to reunite them with the rest of the effigy, citing heritage law requirements.

However, according to Nunami, even the now-distant plinth greatly illustrates the story of Crowther and Lanne better than the statue ever did.

” We get to say we, as the public, learnt, we grew, and we changed the narrative of this place … Look here, we cut that down.”