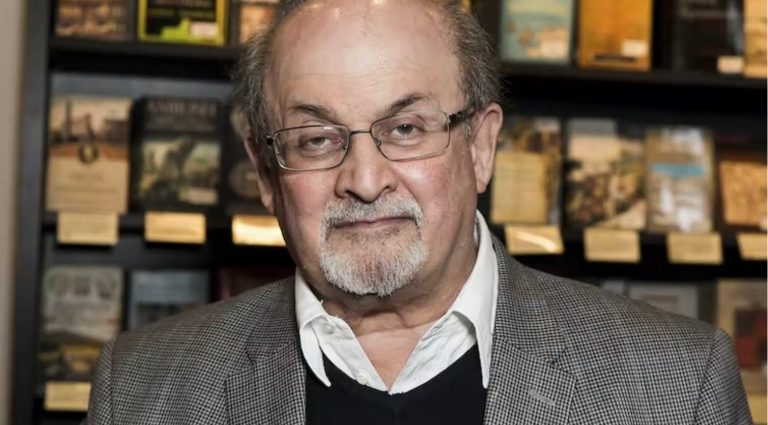

Author Salman Rushdie is in hospital along with serious injuries right after being stabbed by a man at an arts festival in Ny state on Fri. The following article was published on the 30th anniversary of the launch of The Satanic Passages.

One of the most questionable books in current literary history, Salman Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses, ” was published three decades ago this particular month and almost immediately set off angry demonstrations all over the world, a number of them violent.

A year later, in 1989, Iran’s supreme innovator, Ayatollah Khomeini , issued a fatwa , or even religious ruling, ordering Muslims to kill the author. Born within India to a Muslim family, but at that time a British citizen living in the UK, Rushdie was forced to go into protective hiding for the greater portion of a decade.

What was – and still is – behind this outrage?

The dispute

The book, “Satanic Verses, ” goes to the heart of Muslim religious values when Rushdie, within dream sequences, challenges and sometimes seems to mock some of the most sensitive tenets.

Muslims believe that the Prophet Muhammed was went to by the angel Gibreel – Gabriel in English – that, over a 22-year time period, recited God’s words and phrases to him. In turn, Muhammed repeated what to his supporters. These words had been eventually written down and became the verses and chapters of the Koran .

Rushdie’s book takes up these core beliefs. One of the main personas, Gibreel Farishta, has a series of dreams by which he becomes their namesake, the angel Gibreel . In these desires, Gibreel encounters an additional central character in manners that echo Islam’s traditional account from the angel’s encounters along with Muhammed.

Rushdie chooses an attention grabbing name for Muhammed. The novel’s edition of the Prophet is known as Mahound – an alternative name for Muhammed sometimes used throughout the Middle Ages by Christian believers who considered him a devil .

In addition , Rushdie’s Mahound puts his own words into the angel Gibreel’s mouth and delivers edicts to his followers that conveniently bolster their self-serving purposes. Even though, in the book, Mahound’s fictional scribe, Salman the Persian, rejects the authenticity of their master’s recitations, he records them as if they were God’s.

In Rushdie’s book, Salman, for example , attributes certain actual passages in the Koran that location men “in cost of women” plus give men the right to strike wives from who they “fear world of one, ” to Mahound’s sexist views.

Through Mahound, Rushdie appears to cast question on the divine character of the Koran.

Challenging religious texts?

For many Muslims, Rushdie, in his fictional retelling of the birthday of Islam’s key occasions, implies that, rather than God, the Prophet Muhammed is himself the origin of revealed truths.

In Rushdie’s defense, some college students have argued that his “irreverent mockery” is intended to learn whether it is possible to split up fact from fiction. Literature expert Greg Rubinson points out that Gibreel is not able to decide what is real and what is a dream.

Because the publication of “The Satanic Verses, ” Rushdie has argued that religious texts should be open to challenge . “Why can’t we debate Islam? ” Rushdie said in a 2015 interview . “It is possible to regard individuals, to protect all of them from intolerance, while being skeptical about their ideas, even criticizing them ferociously. ”

This view, however , clashes with the view of these for whom the Koran is the literal word of Lord.

After Khomeini’s death, Iran’s government introduced within 1998 that it would not really carry out his fatwa or encourage others to do this. Rushdie now comes from the United States and makes regular public looks.

Still, 3 decades later, threats against their life persist . Although mass protests have stopped, the themes and questions raised in his new remain hotly discussed.

Myriam Renaud is Affiliated Faculty of Contemporary Globe Religions, Union Institute & University

This article is republished from The Conversation under an Innovative Commons license. See the authentic article .