Ryu noted that given the intensifying US-China rivalry, it was in Beijing’s interests for Washington to be tied up in North Korean military threats.

“While Beijing does not deliberately incite instability and conflict on the Korean peninsula, instability on the peninsula – falling short of actual military conflict – would serve Beijing’s interests by diverting the attention and resources of the US and its key allies such as Japan,” he said.

“How much Beijing prioritises the Korean peninsula over other issues such as its rivalry with the US and Taiwan is questionable. Hence it is doubtful if and to what extent Beijing will actually play a constructive role in constraining the North’s provocative behaviour,” Ryu said, adding there was also no guarantee Pyongyang would heed Beijing’s advice or suggestions.

The international community has repeatedly urged China to help to stop North Korea’s military aggression, but Beijing has often hinted that it does not have the required influence over Pyongyang.

“Good relations between China and North Korea and China’s influence on North Korea are two different concepts,” Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning said in September when asked about Seoul’s request for Beijing to do more to rein in Pyongyang.

In an interview with The Telegraph last month, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol said China had an important role to play in regional stability, and he believed China’s alignment with North Korea and Russia would not serve its interests.

Daniel Russel, who served as US assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific Affairs under former president Barack Obama, said Beijing’s “standoffishness” towards the closer alignment between Russia and North Korea was because it did not want to be held accountable for the “misbehaviour of a partner nation”.

“Beijing does not want to pay a price or be held responsible for provocative behaviour by North Korea that China has no control over,” said Russel, who is now vice president of the Asia Society Policy Institute.

“Beijing offers rhetorical and other forms of support to Russia and North Korea where it essentially costs China nothing, but baulks at overt support for their behaviour when it risks retaliation or international condemnation,” Russel said, citing as an example China’s denial of having provided arms for Russia’s war against Ukraine.

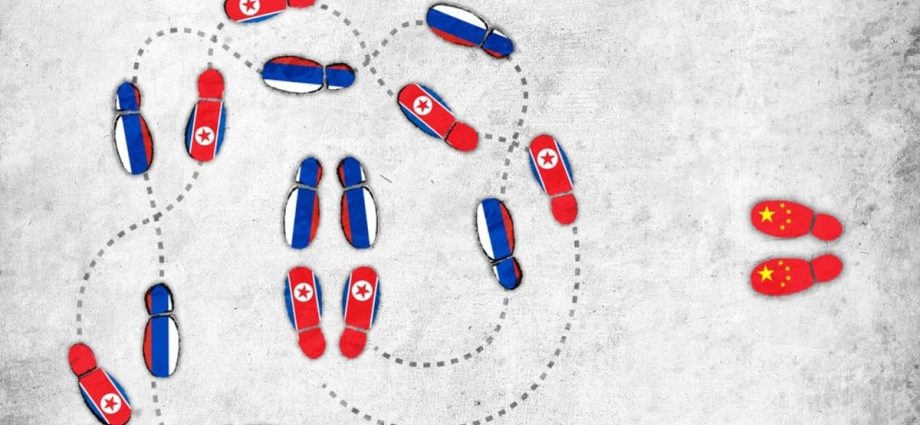

Russel added that China might also be wary of Russia and North Korea’s growing alignment because it could weaken Beijing’s leverage over Pyongyang.

“North Korean leaders have long tried to play one major power off against another, and Kim’s opportunistic embrace of Vladimir Putin is the latest example. Kim is attempting to gain leverage over Beijing – or weaken Beijing’s leverage over him – by showing that he has options other than China,” he said.

Kim told Putin that relations with Russia were the “very first priority” for his country when the pair met in September, prompting speculation about whether Pyongyang had pivoted from Beijing to Moscow.

But he appeared to want to assure Xi that North Korea’s relations with China were “as close as usual”, as he wrote in a letter to the Chinese leader a week after his meeting with Putin.

Deputy Foreign Minister Pak, the first and most senior North Korean official to visit China after the COVID-19 pandemic, vowed during his trip last week to deepen ties to “safeguard common interests”. His visit prompted speculation of paving the way for in-person talks next year between Xi and Kim, who have not met since 2019.

Yun Sun, director of the China Programme at the Washington-based Stimson Centre think tank, doubted that there had been a priority shift in North Korea’s policy.

“China is the single largest supporter of the North Korean economy through aid and trade. It also carries much more influence than Russia does regionally and globally today,” she said.

This article was first published on SCMP.