Tibetan educational sociologist Gyal Lo can speak Mandarin Chinese fluently – but he would rather not.

He has spent the last few years telling the world about Beijing’s sweeping educational reforms in Tibetan areas, and would prefer not to use the language of people he identifies as colonial oppressors.

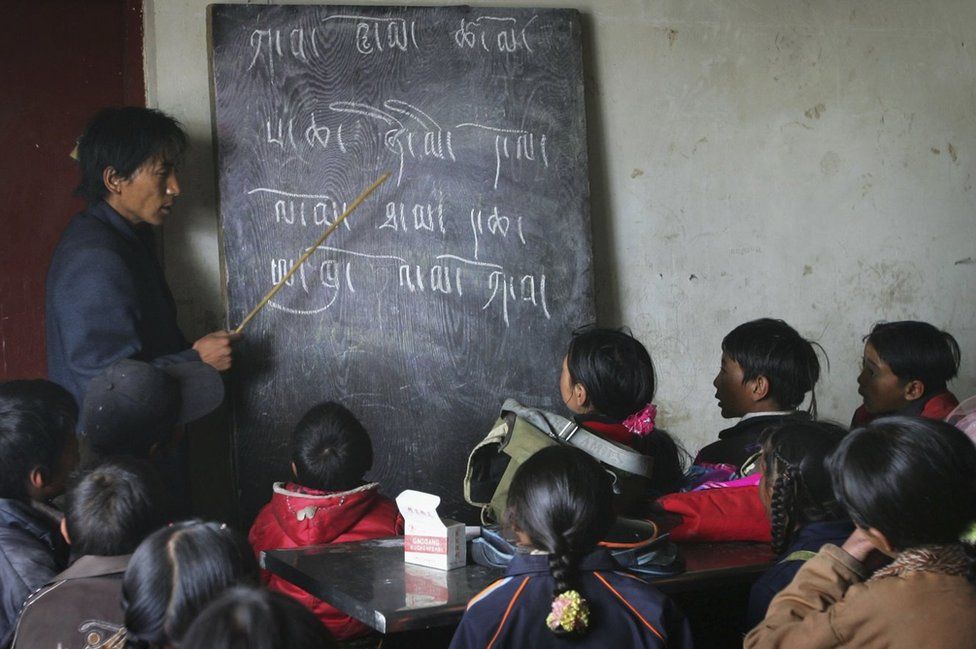

China has expanded the use of boarding schools – for children as young as four – and replaced Tibetan as the main language of tuition with Chinese.

Beijing says these reforms give Tibetan children the best possible preparation for their adult lives, in a country where the main language of communication is Mandarin Chinese.

But Dr Gyal Lo disagrees – he believes Beijing’s real aim is to undermine the Tibetan identity, by targeting the very youngest in society.

“They’ve designed the curriculum that produces a population that will not be able to practise their own language and culture in the future,” he said.

“China is using education as a tool to minimise Tibetans’ social capacity. No one will be able to resist their rule.”

Overseas human rights organisations have for decades been highlighting alleged abuses carried out by China in Tibet – but not much over recent years.

The focus has shifted to Beijing’s treatment of Muslim Uyghurs, in China’s north-western region of Xinjiang, and the pro-democracy protest movement in Hong Kong.

But activists say Chinese officials have been busy in Tibet too.

Over recent years, the Chinese government has closed village schools – and private ones teaching Tibetan – and expanded the use of boarding schools.

These have been in operation for many decades in a number of Chinese regions that are thinly populated – but in Tibetan areas, they appear to have become the main means of education.

Campaigners estimate that 80% of Tibetan children – perhaps one million pupils – are now taught in boarding schools, from pre-school-age onwards.

You can listen to the radio documentary, Educating Tibet, on BBC World Service Assignment here.

In a statement to the BBC, the Chinese embassy in London said this policy was necessary.

“Due to a highly scattered population, children have to travel long distances to get to school, which is very inconvenient,” it said.

“If schools were to be built in every place the students live, it would be very difficult to ensure adequate teachers and quality of teaching. That is why local governments set up boarding schools.”

But opponents say this kind of schooling creates psychological trauma for children who are forcibly separated from their families, who are pressured to send their children away.

“The most challenging aspect of my life was missing my family,” said one Tibetan teenager, who attended a boarding school for several years, until she was 10.

She has since fled Tibet and now lives in India. The BBC spoke to her after making contact through a campaign group.

“There were many other children who missed their families and cried too,” she said. “Some of the younger ones often woke up in the middle of the night crying, and would run to the school gate.”

The BBC spoke to other Tibetan exiles who had heard similar complaints from their relatives still living back home.

Dr Gyal Lo has his own story, about two of his grandnieces, who were sent away to boarding school when they were just four and six.

After observing them at a family dinner, he realised that they felt awkward speaking their mother tongue.

“The way they were sitting there made me think they weren’t comfortable sharing the same identity as their family members. They were like guests,” he said.

It prompted the sociologist, who was then working at the Northwest University for Nationalities in Lanzhou, to visit 50 Tibetan boarding schools to see if other children were the same. They were.

Dr Gyal Lo compares these boarding schools to those that were once operated in the United States, Canada and Australia.

Native children were taken away from their families in a process of assimilation that has now been discredited.

“These kids are completely cut off from their cultural roots, and the emotional connection between their parents, their families and their community,” he said.

The second major change to the education system concerns the Tibetan language, a rich oral and written tradition going back more than one thousand years.

China has replaced Tibetan as the main language of tuition with Mandarin Chinese.

The Chinese embassy said ethnic minorities in China had “the freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages”.

But the student the BBC spoke to said only Chinese was encouraged at her school.

“All the classes were taught in Chinese, except for the Tibetan language class. Our school had a big library, but I didn’t see any Tibetan books there,” she said.

This policy appears to run contrary to international human rights law, according to Professor Alexandra Xanthaki, a UN special rapporteur on cultural rights.

She said parents had the right to send their children to a school that used the language of their choice.

“This means that just one or two hours where it’s being taught as a foreign language is not enough,” she said.

Just over a year ago, Prof Xanthaki and two other UN rapporteurs wrote a letter to China detailing a series of complaints about its educational reforms in Tibet.

The letter suggested China was trying to “homogenise” ethnic minorities, so they would become more Chinese, with Mandarin seen as the vehicle to achieve that goal.

Dr Gyal Lo remembers an argument he had with the vice-president of a university in Yunnan province, where he went to work after Lanzhou. It illustrates how Chinese is valued above other languages.

“He came to my office one day and said, ‘you’re producing Tibetan articles, but not Chinese articles’,” recalled the sociologist.

“It made me uncomfortable and angry. I told him I don’t want produce Chinese articles.” The administrator turned red and stormed out.

Shortly after that incident, in 2020, Dr Gyal Lo fled China and now lives in Canada, from where he campaigns to highlight the educational changes taking place in Tibet.

Beijing is vigorously resisting the narrative put forward by activists like him. It has launched a propaganda campaign to convince the world that its reforms are beneficial.

It has also tried to discredit those who say otherwise. Prof Xanthaki was accused by China of spreading fake news. Dr Gyal Lo has been targeted too. His authority to speak on this issue has been questioned in Chinese state media.

Despite that, he remains undeterred, if pessimistic about the future for Tibetan language and culture, and the region’s young people.

“Our children are becoming an alienated generation. Many will not be able to fit in either Chinese society or Tibetan society.”

-

-

20 April 2023

-

-

-

25 August 2023

-