Every year, Chang Ke-chung journeys from his home in Taiwan to China to carry out a sacred duty.

He worships Mazu, a sea goddess with millions of followers in Taiwan and ethnic Chinese communities around the world. For them, a pilgrimage to Mazu’s home temple in Meizhou in southern China is an essential act of faith.

“We feel we are Mazu’s children, so it’s like we are accompanying our mother to visit her ancestral home,” said Mr Chang, who leads a Mazu temple in Taiwan.

“I’ve been to China so many times now that every time I go there, it’s like I’m home, I’m in my own country.”

Such sentiments delight Beijing but worry Taipei. They put Taiwanese worshippers at the centre of a political tug-of-war, especially with presidential and legislature elections coming up in just two weeks.

Many in Taiwan worship Mazu or other folk deities with roots in China. Religious communities in Taiwan and China share deep and emotional ties, often paying visits to each other’s temples or taking part in religious processions together.

Beijing, which claims self-ruled Taiwan as its own, hopes that this close-knit relationship will pay off in other ways – the more ordinary Taiwanese identify with China, the higher the chances of what it calls “peaceful reunification”.

So the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) allows and encourages Taiwanese temple groups to visit the mainland through its United Front Work Department, which tightly controls religious affairs and influence operations.

Beijing’s official rhetoric pushes for stronger ties. In September, authorities called for expanding religious exchanges in a drive for “cross-strait integrated development”.

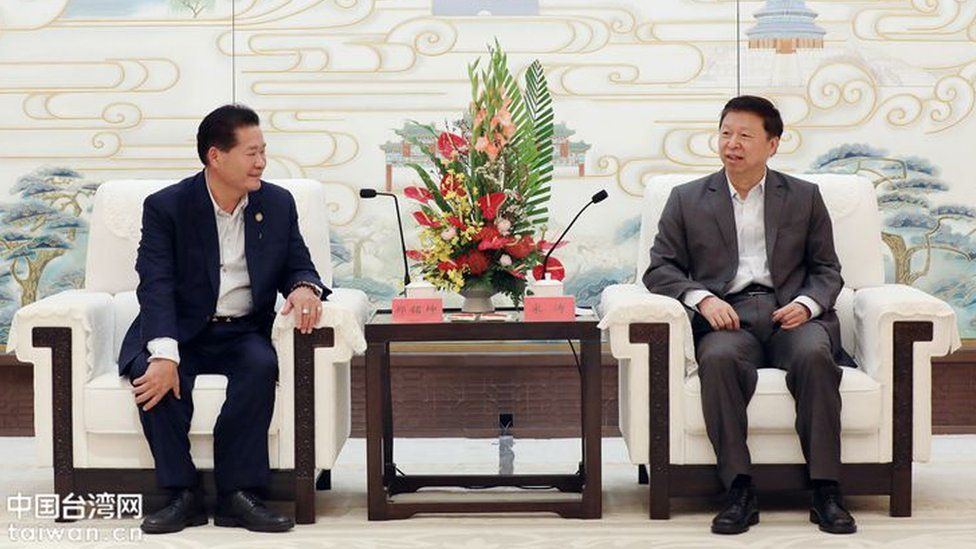

Chinese officials have personally welcomed these groups from Taiwan. In February, when prominent Taiwanese Mazu leader Cheng Ming-kun visited Beijing, he was hosted by Song Tao, the head of China’s Taiwan Affairs Office.

Mr Song called for “spiritual harmony” between China and Taiwan and more frequent exchanges to “jointly create a bright future for reunification”.

Some experts warn that China’s influence could go even deeper.

Most of Taiwan’s 12,000 temples are not officially registered and few release financial statements, making it difficult to track their funding sources. This opens them up to “potential PRC funding”, according to sociologist Ming-sho Ho. There have been calls for stricter regulation and financial scrutiny of temples.

It is no surprise that religion is now “part of China’s grand united front strategy on Taiwan”, says Chang Kuei-min, a religion and politics expert at the National Taiwan University.

“Beijing has used religious lineages to uphold the unification narrative. ‘Homecoming’ and ‘both sides of the Taiwan Strait are one family’ are central themes in cross-strait religious exchange events,” she said.

While Beijing welcomes all Taiwanese religious groups, it has paid particular attention to the Mazu community given their huge size, estimated to be about 60% of Taiwan’s population.

“On a basic level China is using Mazu’s maternal figure to attract [the] Taiwanese,” said Wen Tsung-han, a Taiwan folk religion expert. “You identify with your mother, you identify with Mazu. You identify with Mazu, you’ll then identify with China.”

Under the scanner in Taiwan

This relationship has long troubled the Taiwanese government.

One of the first public controversies happenedin 1987, when it emerged that a prominent Taiwanese Mazu temple group had quietly travelled to Meizhou while Taipei and Beijing had no formal contact. It sparked debate in Taiwan’s legislature and the temple, Dajia Jennlann, was criticised.

Travel restrictions between Taiwan and China eased as their economies grew more intertwined. Now, more than 300,000 Taiwanese devotees visit Meizhou every year, according to Chinese state media.

This has only made the Taiwanese government more suspicious, particularly under the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The DPP, which has ruled the island for the past eight years, insists that Taiwan is sovereign and not a part of China.

Unlike China, Taiwan is a democracy that allows religious freedom – so the government is reluctant to clamp down on the cultural exchanges. But it has stepped up warnings about Chinese influence ahead of January’s election.

The fear is that voters may be inclined towards political parties friendlier to Beijing, such as the DPP’s main rival, Kuomintang (KMT).

In March, the government said those participating in exchanges with China, including religious groups, should “safeguard Taiwan’s best interests”, and anyone caught “engaging in illegal behaviour in cross-strait exchanges” would be dealt with by authorities.

Last month, they banned a Chinese delegation from entering Taiwan for a procession that is a key event in the Mazu religious calendar. It followed concerns from activists and politicians over Beijing’s possible influence on the event.

As they come under greater scrutiny, temple leaders with close links to China insist they have done nothing wrong.

“We are not helping China do unification work, we are helping everyone to communicate… we play a role in cross-strait cultural exchanges so both sides can understand each other more,” Cheng Ming-kun said.

“Mazu is a peace goddess for both Taiwan and China… We are like brothers, with more exchanges you will have less tensions.”

Mr Cheng, who is vice-chairman of the Dajia Jennlann temple and chairman of the Taiwan Mazu Fellowship, characterised his temple’s activities in China as “simple religious exchanges”.

As for why he led a delegation to meet Mr Song in Beijing, he described it as a “rare” networking opportunity for Taiwanese businessmen who are Mazu believers.

When asked if his group received “benefits” from China, Mr Cheng repeated his answer about helping cross-strait relations.

Mr Chang Ke-chung, who leads the Mailiao Gongfan temple in western Taiwan, also denied it and added that his temple’s worshippers paid for their own trips.

But he said United Front officials would sometimes take part in their religious activities in China and mingle with Taiwanese delegates.

“They won’t talk about cross-strait issues,” he said. “When we chat with them it can be quite warm… [we talk about] why is there a need to fight, we are all one people.”

But Taiwan’s religious community does include others who are sceptical of China’s overtures.

“You can deduce that this is unification talk,” said Tan Hong-hui, who works at the Taoist Songboling Shoutiangong temple. “[In Taiwan] we wouldn’t normally say things like ‘blood is thicker than water’ or ‘one family across the Taiwan Strait’, but when you get to China you’ll hear these things.

“If you really say this is simply a cultural activity, I feel that you’re fooling yourself.”

Mr Tan said some temples avoid interacting too much with China, but are now worried about being tarred by the same brush.

“These [cross-strait religious] activities may be cultural in nature, but if the organisers have suspicious backgrounds, it may affect outsiders’ impression of temples.”

Treading a fine line

Even as it tries to combat Chinese influence, Taiwan’s DPP government risks turning away a significant voter base.

Temples are key civic spaces in Taiwan, with two-thirds of the population following folk religions, Buddhism and Taoism. Visiting local temples and taking part in religious events is a must for politicians, especially during election season. In the last presidential election, President Tsai Ing-wen made headlines when she visited a record 43 temples in a month.

The DPP government is already facing a backlash, analysts say. “Some in the religious community feel that the government is targeting them,” said Dr Chang, the religion and politics expert. “Some temples feel their religious motives have been misunderstood.”

Combined with Beijing’s influence, this has contributed to “a phenomenon where some members of these groups are more afraid and may be less trusting of the Taiwanese government”, she added.

For some worshippers, the scrutiny they’re subjected to smacks of hypocrisy.

“They accuse some of going across [to China] to be ‘unified’, but they also show up for temple events, they also take part in temple activities,” said Lee Chin-chen, standing outside the Songshan Ciyou Mazu temple in Taipei. “On one hand you want votes, but behind their backs you criticise them.”

Others like Wang Yu-chiao disagree, saying they are listening: “Everyone knows China will use some tactics to affect the election… they are hoping for Kuomintang to win. We need to be on alert.”

But at the same time “under the DPP Taiwan’s economy these past eight years hasn’t been good,” she added. “Both sides need to maintain exchanges [in general], I think they help Taiwan’s economy.”

“If you have weak self-confidence, then you would be scared of [being a target for] unification,” Mr Lee said.

“You cannot reverse these decades of exchanges, you cannot guard against it… You just need to strengthen yourself, if you become better then you won’t be so scared.”