There was a time when the beneficent smile of a dictator greeted you everywhere in Taiwan.

It’s a far rarer sight now as more and more of those likenesses, which once exceeded 40,000, are removed.

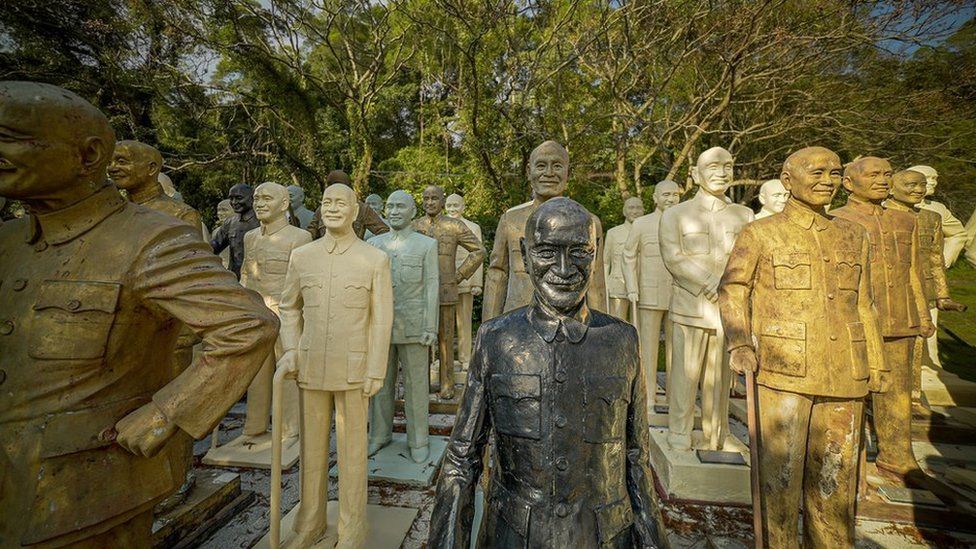

Some 200-odd statues have been stashed away in a riverside park south of the capital Taipei. Here, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek is standing, sitting, in marshal’s uniform, in scholars’ robes, astride a stallion, surrounded by adoring children, and in his dotage leaning on a walking stick.

A democratic Taiwan no longer seems to have room for its erstwhile ruler, who moved the Republic of China here after fleeing impending defeat at the hands of Mao Zedong’s communist forces.

The mainland became the People’s Republic of China, and Taiwan has remained the Republic of China. Both claimed the other’s territory. Neither Chiang, nor Mao, conceived of Taiwan as a separate place with a separate people. But that is what it has become.

Unlike Taiwan, China’s claims never waned. But almost everything else has changed on either side of the 100-mile strait. China has become richer, stronger and an unmistakable threat.

Taiwan has become a democracy and is in the middle of yet another election where its ties with Beijing are being tested. No matter the result of Saturday’s vote, its freedom is a danger to the Chinese Communist Party’s hopes of unification.

There are still those who see themselves, like Chiang, as Chinese – they look to China with admiration and even longing. On the other side are those who feel deeply Taiwanese. They see Beijing as yet another colonising foreign power, like Chiang and the Japanese before him.

There are also 600,000 or so indigenous peoples who trace their ancestry back thousands of years. And then there is a younger, ambivalent generation that is wary of questions about identity. They feel Taiwanese but see no need for Taiwan to declare independence.

They want peace with China, they want to do business with it but they have no desire to ever be part of it.

“I am Taiwanese. But I believe in the Republic of China,” says a woman in her 50s, wrapped in tinsel and Christmas lights, much like Elton John.

This is an uncommon response at an election rally for the Koumintang or KMT, the party Chiang led until his death in 1975. And this is their heartland – Taoyuan County – where tens of thousands have turned out to see their presidential candidate, Ho You-ih.

The KMT is proposing peace and dialogue with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), its old nemesis. Taiwan, it says, can prosper only when it talks to Beijing.

“We should be friends with the mainland,” the woman says, laughing. “We can make money together!”

Her name is impossible to hear over the deafening sound of patriotic rock.

There is a huge roar of approval as Chiang Wan-an, the great-grandson of Chiang Kai-shek and a rising star in the KMT, comes on to the stage.

“I like him very much, he’s very handsome,” says the woman in the tinsel. “I hope he will be president one day!”

The crowd is overwhelmingly those in their 50s or 60s, traditional KMT supporters with family or business ties to the mainland.

“I am Chinese. Taiwan is just a small island. Look at China!” says one man in his 50s, excited about China’s recent spate of space launches. “Of course we should reunify – not now maybe, but one day we must reunify.”

There are few young people in the crowd – those who are don’t seem to be drawn to the KMT’s legacy.

“I’m not voting for the party, I’m voting for the candidate,” says Lin Chen-ze “I am Taiwanese, but I want peace. The [ruling] Democratic Progressive Party has been in power for eight years, it’s time for a change, and Ho You-ih is a good man. He is honest and efficient.”

The answers to a decades-old question – Do you see yourself as Chinese or Taiwanese? – are getting mixed up. For Beijing that is alarming. For Taiwan’s political parties, it is a delicate, new dance, where ideological certainties are being quietly shelved.

“It’s not right what they’ve done to these statues,” says Fan Hsun-chung, a sprightly, 94-year-old veteran, as he walks through the park full of Chiang’s statues.

Fan was 18 in 1947 when he left his home in Sichuan, deep in the mountains of southwest China, to join Chiang’s army. In early 1949, as the Chinese civil war turned dramatically against them, Fan’s unit was shipped to Taiwan to prepare for its use as a bastion.

Six months later Chiang, his government and a defeated army of close to a million men followed.

Fan thought he would return home soon. But after Mao took power, he couldn’t go home, or even write home. “So, I waited and waited, for decades.”

He didn’t see his hometown – far up a tributary of the mighty Yangtze river – until 1990. By then his family was long dead, many of them persecuted by the Communist Party for his actions as a “counter-revolutionary”. His mother and older brother, he learned, had starved to death during Mao’s industrialisation drive, which had triggered a famine.

Despite his seven decades in Taiwan, Fan says he never stopped feeling Chinese: “When we came here our country did not perish; we are still the Republic of China. Taiwan is a province, one of the smallest of more than 30 provinces.”

Not far from here is where Chiang himself lies in unquiet rest: inside a black marble sarcophagus, still unburied nearly half a century after his death.

“We were fighting for the unification of China,” Fan says. “We wanted China to be strong, unified and independent. That was our dream.”

For Chiang, Taiwan was only a stronghold from which to lick his wounds and pursue dreams of reconquering China. The man and his dream may be long dead, but his imprint is obvious.

Walk the streets of Taipei and you are surrounded by names from a bygone era in China: Nanjing East Road, Bei-ping North Road, Chang-an West Road. The language used for education and commerce is Mandarin, a dialect from northern China.

Taipei is a city of wheat noodles and dumplings, again northern fare. There are also plenty of excellent Shanghainese restaurants: a legacy of the exodus of much of that city’s business elite as the communists took power.

But Chiang’s legacy came at a huge cost. Any expressions of Taiwanese political identity were ruthlessly crushed. Many thousands were tortured, imprisoned and executed under Chiang, whose personality cult rivalled that of Mao, Stalin or Kim Il Sung. The period entered the history books as the White Terror.

The KMT and the CCP are “like identical twins with the same mindset”, says 86-year-old John Chen, a political activist. “They both have this idea that we are all part of Greater China.”

Chen is walking through the cell block of an old military detention centre on the south side of Taipei – a place he knows all too well.

In 1969, a military court tried and jailed him here. He had been married three weeks. He spent the next 10 years in Jing Mei, one of Taipei’s most feared prisons. His crime: taking part in a pro-Taiwan independence group while in medical school in Japan.

He shared the cramped cell with six other inmates. They had no bunks, only a squat toilet in the corner and a tap and a bucket to wash. They sweltered in the summer and froze in the winter. They were allowed out for exercise for just 15 minutes a day.

Chen, who was born under Japanese rule, speaks fluent Japanese, and admits to feeling more affinity with the ways of Japan than with those of mainland China.

“I don’t consider myself Chinese. I am Taiwanese,” he says.

Chen is among the many millions – the majority of the island – whose families emigrated from China. They largely came from Fujian in several waves starting in the early 1600s. They speak Taiwanese, a version of southern Fujian dialect, as different from Mandarin as English is from Portuguese.

To him, “Taiwan is already independent” and the future is bright.

“One day the Chinese Communist Party will collapse. And when it does, we can fully join the international community.”

He dismisses Beijing’s claims that Taiwan is part of China because they share a common culture and language.

“Where does that leave Tibet or Xinjiang? And if the Chinese nation is built on being Chinese or speaking Chinese, what about Singapore?”

The era of military rule is long over, and monuments across Taiwan commemorate the White Terror.

But Beijing’s persistent claims, some argue, are making a bristling, younger generation rethink how they see themselves.

Lōa Ēng-hôa began learning Taiwanese about five years ago. Now he only speaks in Taiwanese, or English, but refuses to speak in Mandarin.

To him it is the language of a colonial oppressor. He likens it to British people being forced to speak Italian because England was once part of the Roman Empire.

“When I was at elementary school, we would gather each morning and sing the [Republic of China] national anthem. And there were always some lazy students who didn’t bother singing, and I would shout at them ‘don’t you love your country!’ I really thought I was Chinese.”

He says it was only when he went to work in Australia and saw how it was dealing with its turbulent history, that he began to awaken to his identity.

Under KMT rule, school children were forbidden from speaking Taiwanese and punished if they did. Taiwanese parents made their children speak Mandarin, even at home, believing that it would help them get into university or find a good job.

Lōa says Taiwanese may not be banned but its ” ideological dominance” persists.

“And the most important thing is that we are still denied the right to be educated in Taiwanese – 80% of people are ethnically Taiwanese, but we don’t have the right to be educated in our own language. How ridiculous is that?”

For young people like him, the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which once called for Taiwanese independence and whose success grew out of anti-Beijing sentiment, is not going far enough.

The DPP was once a ragtag outfit that struggled to win local elections and parliamentary seats. Taiwanese was the language of its rallies. Now, it’s the party of power. It has ruled for 16 years in total, including the last eight.

Now its young supporters speak fluent English and are passionate about the environment and LGBTQ rights, more so than any urgent need for formal Taiwan independence.

At a recent rally in Taipei, the DPP’s vice-presidential candidate, Hsiao Bi-khim made her first big public address. Young and charismatic, she was a big hit with the crowd.

In Beijing, she is loathed: born in Japan to an American mother and Taiwanese father, Hsiao’s most recent job was as Taiwan’s de-facto ambassador to the United States. China’s state media has been busy spreading rumours that she can barely speak Mandarin, which is untrue.

But China fears the rise of politicians like Hsiao, who have almost no family ties to the mainland, and see Taiwan as closer to Tokyo and Washington than Beijing.

Beyond the DPP, this is the first election where all three presidential candidates are of Taiwanese descent. None are from families that came to Taiwan with Chiang in 1949. The KMT’s Hou is the son of a market trader from southern Taiwan who climbed through the ranks of the police force to head the national investigation bureau.

Today, the DPP no longer talks about the need for formal independence and the KMT speaks of dialogue with Beijing, but sidesteps the subject of unification, or whether Taiwan is part of China.

Both are now embracing Taiwan’s peculiar “status quo”- it elects its own leaders, but it is not considered a country.

At the KMT rally, the woman in tinsel summed it up bluntly: “This is the mountain protecting us. Without the Republic of China [status], Taiwan is finished. Taiwan can’t be independent. Independence means war.”

This is what experts call “strategic ambiguity”. So far it has satisfied everyone, including Beijing. But that is not how people define who they are.

“We are all Taiwanese today regardless of where our grandparents came from. We inter-marry and mix Taiwanese and Mandarin when we speak to each other,” say a group of hikers on a trail near Taipei.

When they travel abroad, they say they are from Taiwan. “We do not want people to think we are from China.”

That is a problem for Beijing – because they are deciding what they want to be.

And that runs counter to the CCP’s message – a unified China under the rule of the Communist Party. It’s a message that has been delivered to Tibetans, Uyghurs, Mongols – and Hong Kong.

Not everyone feels Taiwanese, or exclusively Taiwanese, but more and more young people seem to lean this way, polls suggest.

Even in this new Taiwan, Chiang’s family name counts. Many here say they would like to see the KMT nominate his great-grandson in 2028. And Hsiao has been touted as a contender for the DPP.

Either could win, but the challenge for China is that the Taiwanese will decide.

Young voters say all they care about is peace: “I have two younger brothers and I am very worried they will end up fighting in a war with China,” says 21-year-old Shen Lu at the KMT rally.

Like their most powerful allies, few Taiwanese talk of independence because that feels impractical, even impossible. But peace has become a refrain for keeping what they have – whatever they might choose to call it.

“I am Taiwanese but the most important thing for my generation is peace,” Shen says. “I don’t want unification. I want the situation to stay as it is now. We should keep it like this forever.”