Australia editor

With a pair of beautiful green tweezers in hands, Emma Teni is carefully wrestling a big and slender spider in a small plastic pot.

The spider-keeper makes fun of itself as it rears up on its back arms and says,” He’s posing.” She is attempting to do exactly what she is trying to do: using a tiny dropper, she can swallow the poison out of its claws.

Emma works from a small company known as the spider milk area. She milks or extracts the poison from 80 of these Sydney funnel-web ants on a normal day.

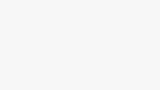

On three of the four rooms, there are floor-to-ceiling aisles full of the spiders, and a black veil has been pulled across to keep them calm.

The remaining walls is actually a windowpane. A young child gazes at it while Ms Teni is working, both fascinated and horrified. Little do they realize that the palm-sized insect she’s management may be fatal in a matter of seconds.

” Sydney funnel-webs are possibly the most dangerous spider in the world”, Emma says matter-of-factly.

This area at the American Reptile Park plays a crucial role in a government initiative that saves lives on a continent where it’s frequently joked that everyone wants to kill you. Australia is renowned for having such dangerous animals.

Spider child

While the quickest recorded dying from a Sydney funnel-web insect was a child at 13 days, the average is closer to 76 moments- and second support gives you an even better chance of surviving.

Nobody has been killed by an antivenom since it first started at the American Reptile Park because it has been so powerful.

However, the system relies on the public to either collect their egg sacs or catch the spiders.

In a van plastered with a large crocodile sticker, each year Ms Teni’s group drives all over Australia’s most popular city, picking up Sydney funnel-webs that have been handed in at drop-off points such as local clinical practices.

These spiders are incredibly dangerous because of two things, she explains: first, they have a very high level of poison, and they live simply in densely populated areas where they are more likely to encounter people.

Charlie Simpson, a plumber, is one of those people. He moved into his first house with his partner a few months ago, and the enthusiastic gardener has now found two Sydney funnel-webs. The vet took the second spider, and Ms Teni picked it up immediately after.

The 26-year-old claims that because their fangs are so large and powerful,” I had gloves on at the moment, but honestly I should have had set gloves on.”

” I]just thought ] I had better catch it because I kept getting told you’re meant to take them back to be milked, because it’s so critical”.

He makes up his joke,” This is calming my spider phobia.”

She insists that her crew isn’t telling Australians to” put themselves into threat” as one spider that was delivered to her in a Vegemite pot is offloaded.

Instead, they’re asking that if someone comes across one, they carefully get it rather than eliminate it.

It sounds counter-intuitive to say that this is the world’s most dangerous spider before [inviting the public to ] get it and bring it to us, she says.

However, Charlie says that spider is here today, and it will… successfully save someone’s life.

All of the spider her team collects find brought up to the American Reptile Park where they are catalogued, sorted by gender and stored.

Any women that are dropped off are enrolled in a breeding program that raises money for the number of ants that the general public donates.

The men, who are six to seven days more dangerous than the ladies, are milked every two weeks and used for the antivenom program, according to Emma.

The syringe she uses to remove the venom from the fangs is attached to a suction hose- essential for collecting since many venom as probable, since each spider provides just small amounts.

While a few drops are enough to kill, scientists need to milk 200 of these spiders to make enough to fill a vial of antivenom.

Emma, a marine biologist by training, never anticipated going out to spend her days milking spiders. In fact, she started off working with seals.

She would no longer have it in any other way, though. Emma, who is known as” spider girl,”” spider mama,” and even “weirdo,” as her daughter affectionately refers to her, loves all things arachnid.

Friends, family and neighbours rely on her for her knowledge of Australia’s creepy crawlies.

” Some girls come home to flowers on their doorstep,” exclaims Emma. It’s not unusual for me to find a spider inside a jar when I travel home.

The best place to be bitten?

The Australian Reptile Park’s activities only take the form of spiders. Additionally, it has been giving snake venom to the government since the 1950s.

According to the World Health Organisation, as many as 140, 000 people die across the world from snake bites every year, and three times that many are left disabled.

However, thanks to Australia’s successful antivenom program, those numbers are much lower: between one and four people are hired each year.

When Billy Collett, the park’s operations manager, removes a King Brown snake from its storage locker, he reaches it to the table in front of him.

With his bare hands, he secures its head and puts its jaws over a shot glass covered in cling film.

As yellow venom drips down the bottom, Mr. Collett describes them as being “very uninclined” but once they go, you just see it pouring out of the fangs.

That would kill everyone in the room five times, perhaps more, according to the statement.

Then he switches to a more reassuring tone:” They’re not looking for people to bite. We’re too big for them to consume, and they don’t want to eat us because they want to squander their fury. They simply want to be left alone.

” To get bitten by a venomous snake, you’ve got to really annoy it, provoke it”, he adds, noting that bites often occur when someone is trying to kill one of the reptiles.

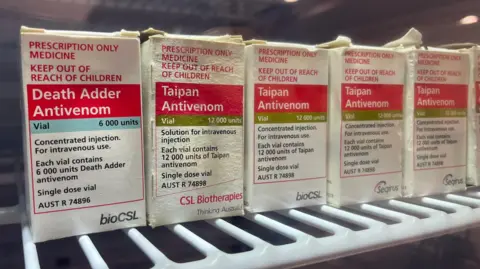

In the corner of the room, where Mr. Collett is collecting the raw venom is kept, is a fridge. It has packages titled” Eastern Brown,”” Taipan,”” Tiger Snake,” and” Death Adder.”

The last of these is the second-most venomous snake in the world, and the one that’s most likely to bite you here, in Australia.

This venom is freeze-dried and sent to CSL Seqirus, a lab in Melbourne, where it is transformed into an antidote in a procedure that can take up to 18 months.

The first step is to create what is known as hyper-immune plasma. In the case of snakes, controlled doses of the venom are injected into horses, because they are larger animals with a strong immune system.

Rabbits, which are immune to the toxins, are fed with the poison from Sydney funnel-web spiders. The animals are given increasing amounts of antibodies as they grow. In some cases, that step alone can take almost a year.

The supercharged plasma of the animal is taken from the blood, and the antibodies are extracted before being bottled and given to the patient.

CSL Seqirus distributes 7, 000 vials annually that include antivenoms from box jellyfish, snakes, spiders, stonefish, and box jellyfish. They are valid for 36 months. The challenge then is to ensure everyone who needs it has supplies.

Dr. Jules Bayliss, who leads the CSL Seqirus team’s antivenom development team, describes it as” an enormous undertaking.”

” We want to see them in the major rural and remote areas that these creatures are most likely to be in,” says the company.

Vials are distributed depending on the species in each area. Taipans, for instance, are found in northern regions of Australia, so there is no need for their antivenom in Tasmania.

The Royal Flying Doctors, who visit some of the country’s remote communities, as well as the Australian navy and cargo ships for sailors who are at risk of sea snake bites, receive antivenom as well.

Papua New Guinea also receives about 600 vials a year. The Australian government once had a land bridge connection with Australia, and the two countries shared many of the same snake species. If you want to practice snake diplomacy, visit the country.

Because of the number of snake bites and deaths they have, according to CSL Seqirus executive Chris Larkin,” we probably have the most impact in Papua New Guinea, more so than Australia,” Larkin says. To date, they reckon they’ve saved 2, 000 lives.

Mr. Collett makes fun of the nickname “danger noodles” that his serpentine coworkers occasionally receive, a classic Australian way to make light of something that causes nightmares for so many visitors.

However, Mr. Collett is clear that visitors should not be turned off by these creatures.

” Snakes aren’t just cruising down the streets attacking Brits- it doesn’t work like that”, he jokes.

Australia is the best place to be if you’re going to get bitten by a snake; we have the best antivenom. It’s inexpensive. The treatment is unreal”.