Did Shangri-La give birth to a new Quad?

The recently-concluded Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore was among the most high-stakes confabs in recent years, as multiple powers explored ways to avoid a full-blown New Cold War and armed confrontation between the US and China.

But with no sign of any immediate thaw between the two superpowers, new, inchoate security groupings are emerging on the margins.

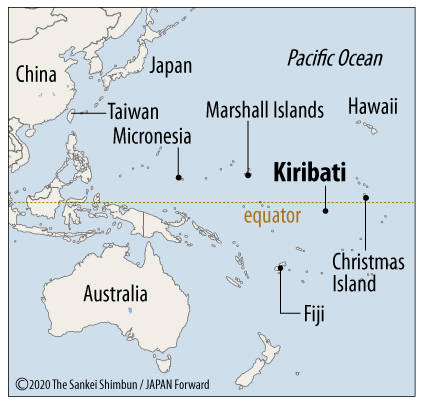

After months of intense anticipation, defense chiefs from the US, the Philippines, Australia and Japan held their first-ever quadrilateral talks on the sidelines of the Shangri-La forum, with Beijing’s maritime assertiveness in mind.

US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin, Japan’s Defense Minister Yasukazu Hamada, Australian Defense Minister Richard Marles and Philippine Acting Defense Secretary Carlito Galvez held an unprecedented meeting with huge symbolic and big operational implications.

Atop their agenda was proposed quadrilateral joint patrols in the South China Sea for later this year, which if held would mark a major milestone for America’s evolving “integrated deterrence” strategy to contain China’s rise in the region.

Although playing down the idea earlier this year, Washington seems increasingly open to new quadrilateral mechanisms beyond its existing “Quad” partnership with India, Australia and Japan, which by accounts has been beset by internal divisions over confronting Russia in the wake of the Ukraine conflict.

Over the weekend, yet another incident served as a stark reminder of rising geopolitical volatility in the Indo-Pacific. Following a rare joint sail by US and Canadian naval forces through the Taiwan Straits, Beijing responded with aggressive counter-maneuvers and strident diplomatic protests.

During a “routine” transit through the area, the US Navy’s 7th Fleet said the guided-missile destroyer USS Chung-Hoon and Canada’s HMCS Montreal reportedly came close to blows with a Chinese navy ship, which cut across the bow of the American destroyer on two occasions.

Just days earlier, the Pentagon released footage that showed a Chinese fighter jet performing a similar maneuver, albeit in the skies, against an American surveillance aircraft.

Rising tensions in the seas and the skies were mirrored by tough diplomatic exchanges between US and Chinese defense chiefs at the Singapore forum. For his part, China’s defense chief Li Shangfu warned against a “Cold War mentality” in a not-so thinly-veiled jab at the Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) alliance and Quad.

“In essence, attempts to push for NATO-like [alliances] in the Asia-Pacific is a way of kidnapping regional countries and exaggerating conflicts and confrontations, which will only plunge the Asia-Pacific into a whirlpool of disputes and conflicts,” the Chinese official warned while reiterating an uncompromising position on Beijing’s plans to “reunify” self-ruling Taiwan.

For his part, US defense chief Austin warned against any aggressive maneuvers against Taiwan while underscoring his vocal concerns over the virtual breakdown of military-to-military communication channels with China.

“I am deeply concerned that the PRC (People’s Republic of China) has been unwilling to engage more seriously on better mechanisms for crisis management between our two militaries,” Austin said during his speech in Singapore.

“The more that we talk, the more that we can avoid the misunderstandings and miscalculations that could lead to crisis or conflict,” he added.

The deadlock in Sino-American relations has likely forced Washington to reconsider its earlier apprehensions with new Quad groupings in the region.

Earlier this year, US Assistant Secretary of State Daniel Kritenbrink, during a regional tour in Asia, played down suggestions of a new Quad grouping, including by Philippine Senator Francis Tolentino, who has pushed for “own version of Quad” to check China’s ambitions in adjacent waters.

“I guess regarding what you called, a new Quad, I would say, ‘no.’ We’re not looking to establish a new quad,” Kritenbrink said in an online press briefing during his Manila visit last month.

“We’re not looking to establish any new formal mechanisms in the Indo-Pacific at this point,” the senior US diplomat said, adding how his country is “happy to assist with the ongoing modernization of the Armed Forces of the Philippines including in the maritime domain.”

Nevertheless, Kritenbrink left the door open for “opportunities in the future for such close allies as the United States, Philippines and Japan to look at ways that maybe we could expand our cooperation” amid growing discussions over a trilateral Japan-Philippine-US (JAPHUS) security grouping.

Following Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr’s consequential visit to the White House and the Pentagon last month, which saw the two treaty allies sign new bilateral defense guidelines, moves to forge de facto alternative quadrilateral groupings are accelerating.

Historically, Manila served as a venue for the two key moments in the birth of the original Quad. The first US, Australia, India, and Japan inaugural meeting took place on the sidelines of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) gathering in Manila in 2007. Exactly a decade later, the leaders of the four powers, wearing traditional Filipino barongs, held their first formal official-level discussions also in Manila.

Now, the US is overseeing the emergence of a new quadrilateral grouping, especially with the Philippines’ emergence as a new star ally in Asia under a more Western-friendly regime.

During the Shangri-La Dialogue, Philippine Defense Chief Carlito Galvez took an uncompromising position on the South China Sea disputes, signaling Manila’s hardening line against China’s assertiveness over its claimed features and islands.

“We view the 2016 arbitration award as not only setting the reason and right in the South China Sea, but also as an inspiration for how matters should be considered by states facing similar challenging circumstances,” Galvez said before his Indo-Pacific counterparts.

“President Ferdinand Marcos Jr has strongly emphasized his directive to safeguard every square inch of our territory from any foreign power… The UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea) and the 2016 arbitration are and will continue to be the twin anchors of our policies and actions in the West Philippine Sea and the broader South China Sea,” he added while emphasizing his country’s commitment to enhance maritime security cooperation with like-minded powers.

Last week, the Philippines, Japan and US held their first-ever joint coast guard drills in Manila Bay. Later this year, the US and its regional allies including the Philippines are expected to conduct potentially unprecedented quadrilateral joint patrols in the South China Sea.

Closer intelligence-sharing, expanded joint drills and arms transfers among the four allies are likely to follow, with Tokyo exploring its own visiting forces agreement with Manila, which has already hosted large-scale US and Australian military presences in the past decade.

In an official statement following the inaugural Philippine, US, Japan and Australia quadrilateral meeting in Singapore, Japan’s Ministry of Defense said that the four allies “discussed regional issues of common interest and opportunities to expand cooperation,” while vowing to double down on new and pre-existing cooperative agreements.

“It was an honor to meet with Secretary Galvez, Minister Hamada, and DPM Marles to discuss opportunities to expand cooperation across our four nations, including in the South China Sea,” Austin said in a tweet after the meeting. “We are united in our shared vision for advancing a free and open Indo-Pacific,” he added.

Follow Richard Javad Heydarian on Twitter at @Richeydarian