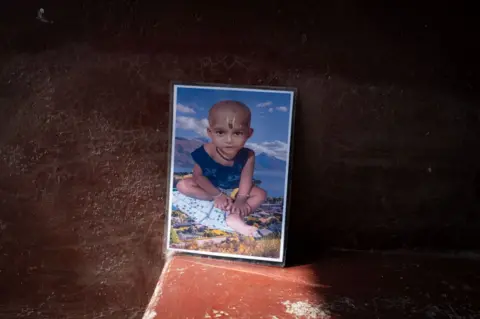

Swastik Pal

Swastik PalMangala Pradhan did not forget the day her one-year-old boy was lost.

It was 16 years earlier, in the cruel Sundarbans- a huge, terrible river of 100 islands in India’s West Bengal state. Her child Ajit, just beginning to wander, was full of life: playful, anxious, and wondering about the globe.

That night, like so many others, the household was preoccupied with their daily tasks. Raja had been fed breakfast and taken to the home by Mangala as she prepared the meal. Her father was out buying fruits, and her ailing mother-in-law rested in another area.

But little Raj, often eager to explore, slipped away undetected. Mangala shouted for her mother-in-law to observe him, but there was no reply. Minutes later, when she realised how peaceful it had become, panic set in.

” Where is my son? Has anyone seen my child”? she screamed. Neighborhoods rushed in to assist.

Desperation quickly turned to heartbreak when her brother-in-law found Ajit’s tiny body floating in the pond in the courtyard outside their ramshackle home. The little boy had wandered out and slipped into the water – a moment of innocence turned into unthinkable tragedy.

Swastik Pal

Swastik PalOne of 16 parents in the area immediately, Mangala, walks or cycles to two wooden preschools set up by a non-profit where they care for, feed, and teach about 40 kids who are dropped off by their parents on their way to work. According to Sujoy Roy of Child In Need Institute ( CINI), which built the creches,” These parents are the saviors of children who are not their individual.”

In this aquatic area, which is dotted with ponds and rivers, many children proceed to drown. The need for such care is essential. Every home has a water used for cleaning, washing, and also drawing drinking water.

Almost three children between the ages of one and nine years per day drowned in the Sundarbans area according to a survey conducted by the clinical research organization The George Institute and CINI for the year 2020. Incidents peaked in July, when the rain rains began, and between ten in the morning and two in the evening. The majority of children were unsupervised at the time because the caretakers were busy with responsibilities. Around 65 % drowned within 50m of home, and only 6 % received care from licensed doctors. Healthcare was in disrepair: there were few facilities and a lot of common health facilities were shut down.

Swastik Pal

Swastik PalIn reaction, villagers clung to old superstitions to keep rescued children. They spun the boy’s body over an individual’s mind, chanting devotions. They use stones to repel spirits and hit the water against the spirits.

” As a mom, I know the pain of losing a child”, Mangala told me. I don’t want any other mothers to go through what I did. These kids need my help to prevent swimming. We live amid so numerous problems anyway”.

Living in Sundarbans, apartment to four million people, is a daily battle.

Tigers, known to attack humans, roam dangerously close to and enter crowded villages where the poor eke out a living, often squatting on land.

People fish, collect sweet, and obtain lobsters under the constant risk of lions and poisonous snakes. From July to October, rivers and ponds swell due to heavy rains, storms whip the place, and rampaging lakes eat villages. Climate change is worsening this confusion. Here, there are approximately 16 % of the population aged one to nine.

Swastik Pal

Swastik Pal” We’ve often co-existed with liquid, unaware of the dangers, until horror strikes”, says Sujata Das.

Sujata’s existence was overturned three months ago when her 18-month-old child Ambika, drowned in the water at their mutual relatives house in Kultali.

An older aunt was busy at home, her children were attending their training lessons, and some of her family members had gone to the business. Her father, who typically works in the southern state of Kerala, was home that evening, repairing a hunting web at the local trawler. Sujata had gone to a nearby handpump to get water because a guaranteed ocean network at her house had not yet arrived.

Next, we discovered her in the water floating. It had rained, liquid had risen. We took her to a nearby doctor, who declared her dying. According to Sujata, this horror has taught us what we should do to stop calamities like this in the future.

Swastik Pal

Swastik PalSujata and other villagers have plans to use wood and nets to fence their water to stop children from scurrying into the liquid. She hopes that town ponds are where babies who are unable to learn how to swim. She wants to encourage neighbors to practice CPR so that they can give lifesaving assistance to freed drowning children.

” Kids don’t vote, but the political will to address these issues is often lacking”, says Mr Roy. ” That’s why we’re focusing on building local tenacity and spreading information”.

Over the past two decades, around 2, 000 people have received CPR education. A peasant revived a drowning baby before he was taken to the hospital last July, saving him. ” The real problem lies in setting up preschools and raising knowledge in the community,” he continues.

According to costs and regional beliefs, even basic solutions are challenging to implement.

Swastik Pal

Swastik Pal Swastik Pal

Swastik PalSuperstition about enragening liquid gods made it difficult for people in the Sundarbans to fence their ponds. In neighboring Bangladesh, sturdy playpens were introduced in patios to protect children, where drowning is the main cause of death for children aged one to four. But, conformity was lower- children disliked them, and villagers frequently used them for goats and ducks. ” This created a false sense of security, and drowning rates significantly increased over three times”, says Jagnoor Jagnoor, an injury epidemiology at the George Institute.

Eventually non-profits set up 2, 500 creches in Bangladesh, cutting drowning deaths by 88 %. In 2024, the authorities expanded this to 8, 000 areas, benefitting 200, 000 children periodically. Water-rich Vietnam focused on children between the ages of six and ten, using decades of mortality data to create policies and train success skills. This reduced swimming costs, particularly among children who are navigating the water.

Swastik Pal

Swastik Pal Swastik Pal

Swastik PalDrowning continues to be a significant global problem. In 2021, an estimated 300, 000 persons drowned- over 30 life lost every afternoon, according to the WHO. Almost half of them were under 29 and a fourth were under five. India’s information is sparse, actually recording around 38, 000 drowning deaths in 2022, though the real number is likely much higher.

In the Sundarbans, the unpleasant truth is ever-present. Kids have been given years to travel freely or to be tied with ropes and linen to stop wandering. Jingling bracelets were used to warn parents to their children’s movements, but in this cruel, water-surrounded scenery, nothing feels really safe.

Last summer, Kakoli Das ‘ six-year-old boy walked into an overflowing pond while handing a piece of paper to a neighbor. Unable to differentiate between the road and the ocean, Ishan drowned. He had seizures when he was a kid, and because of the risk of disease, he was unable to learn to swim.

” Please, I beg every family: gate your lakes, learn how to revive kids and tell them how to swim. This is about saving livelihoods. We may manage to wait”, says Kakoli.

The preschools offer a way to protect children from the consequences of water for the time being, serving as a beacon of hope. On a new day, four-year-old Manik Pal sang a cheerful lyric to remind his friends: I didn’t go to the water alone/ Unless my kids are with me/I’ll learn to swim and be afloat/And live my life fear-free.