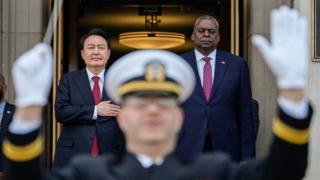

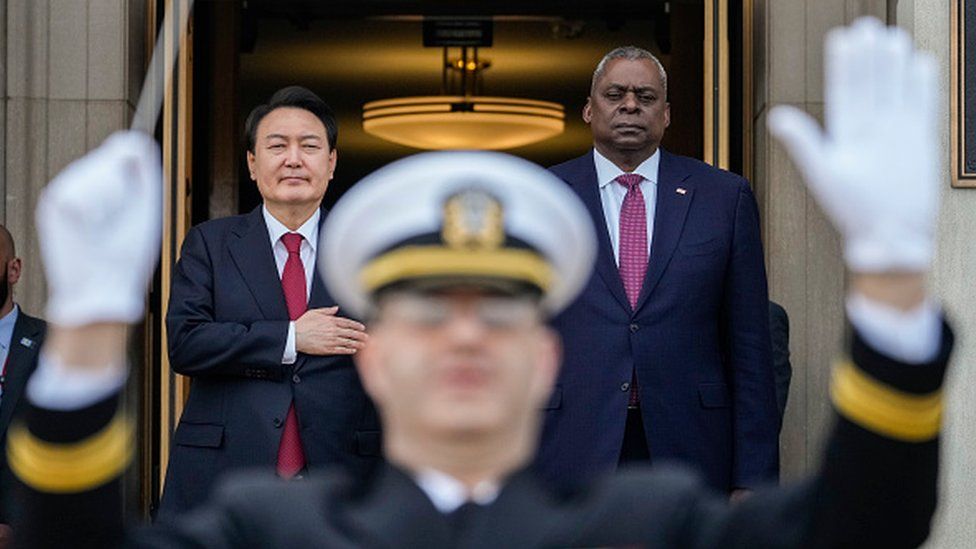

On Sunday, when South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol hosted US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin at his home for dinner, he urged Mr Austin to be vigilant against any type of North Korean attack, including surprise assaults “resembling Hamas-style tactics”.

Ever since Hamas launched its brutal cross-border attack on Israel on 7 October, South Korean politicians and defence chiefs have invoked comparisons between that and what Pyongyang might do to the South.

Last month the Chair of South Korea’s Joint Chiefs of Staff also said that if Pyongyang was to wage war on the South in the future, there was evidence to suggest “it could follow a similar pattern to the Hamas invasion”.

But is South Korea really at risk of a similar attack, or has the conflict merely given it a reason to beef up its defences and get tougher on North Korea?

Like Israel, South Korea lives next door to an enemy which has frequently threatened to annihilate it.

Hamas’s assault on Israel, where rockets were fired into its territory as guerrilla fighters invaded, is a prime example of what is known as hybrid warfare. Ryu Sung-yeop, a research fellow at the 21st Century Military Studies Institute, noted that this is something North Korea has traditionally been very good at, adding that if it were to engage in an hybrid war, Seoul would suffer.

While Hamas fired 5,000 rockets into Israel in the early hours of 7 October, Pyongyang’s artillery could fire an estimated 16,000 rounds an hour. To combat the threat, Seoul is developing its own missile defence system, similar to Israel’s Iron Dome.

And just like what Hamas has done in Gaza, the North is also thought to have built a network of underground tunnels, some running under the Demilitarised Zone (DMZ), which could be stocked with weapons and used in a potential invasion.

How real is the threat from the North?

The threat of North Korea has been omnipresent in the South for decades, and current tensions between the two Koreas are especially high.

However its last significant attack came 13 years ago, when soldiers shelled a South Korean island, killing two marines and two civilians.

Security experts say that North Korea’s strategy has evolved since then, meaning its goal in a conflict would no longer be to breach the border, but to destroy the capital Seoul.

“While Hamas mainly relied on short range rockets, North Korea has a much bigger range and variety of artillery. Its strike capability is many more times that of Hamas,” Hong Min, the Director of North Korean Research at the Korea Institute for National Unification, said.

In recent years, Pyongyang has focused on improving and increasing its arsenal of nuclear weapons, claiming to have developed short-range ballistic missiles capable of carrying tactical nuclear weapons. This means North Korea now has no reason to use similar tactics to Hamas, which is a militant group, according to Cho Seong Ryul, a former defence advisor to the government. “North Korea is a sovereign country, with its own army and nuclear weapons.”

Mr Cho, now a military studies professor at Kyungnam University, also argued that North Korea had “no incentive to go to war right now,” given that they already have an independent state.

Furthermore South Korea and the US have repeatedly made it clear that any attack on the South would result in the end of the Kim regime, and Kim Jong Un’s top priority has always been his regime’s survival.

Even so, the attack on Israel has led the conservative government in South Korea to question whether security along the border is as tough as it could and should be. The administration has taken a hard line on North Korea, prioritising military strength and the threat of retaliation over dialogue and engagement.

Specifically, it has criticised a military agreement, signed by the North and South in 2018 under the country’s previous administration, which was intended to prevent cross-border skirmishes and attacks.

The deal created a no-fly zone, prohibiting both sides from operating military aircraft or surveillance equipment near the border. South Korea’s recently appointed defence minister, Shin Won-sik, has now proposed scrapping the agreement, in order to have surveillance drones monitor the North.

“The 2018 military agreement has greatly limited our surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities,” Mr Shin said in the wake of Hamas attack. He added that if Israel had kept a better eye on its border with Gaza, it could have reduced the number of casualties.

Although North Korea has breached the deal several times since 2018, the number of skirmishes has reduced, leaving some experts to suggest that getting rid of it would inflame tensions and make an attack more likely. “Scrapping the agreement may slightly improve real-time monitoring close to the border, but not in a significant way”, Hong Min, from the Korea Institute for National Unification, noted.

Mr Hong said the focus should be instead be on preventing the North from attacking in the first place.”At this point there is nothing any country can do to completely protect against all of North Korea’s arsenal if, like Hamas, it decides to launch everything all at once.”