Getty Images

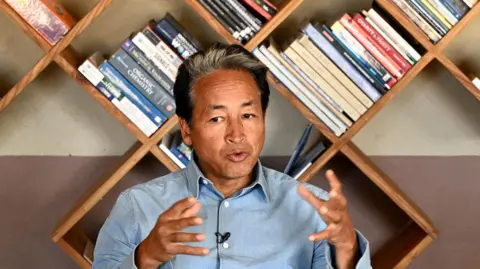

Getty ImagesAn American climate activist who ended a 16-day hunger strike this year claims that his fight to protect the ecology of his home, an icy, cool desert in the country’s northern region, is still far from over.

Sonam Wangchuk, 58, gained notoriety in India when Bollywood actor Aamir Khan portrayed a figure in the 2009 hit film 3 Stupid.

Additionally, Mr. Wangchuk has worked as an entrepreneur and expert for a long time. However, he has recently gained media attention for holding demonstrations against greater autonomy for residents of his native Ladakh, a hilly, cold plain bordering Pakistan and China.

Ladakh was part of Indian-administered Kashmir until 2019, when Prime Minister Narenda Modi’s government removed the state’s special status and split it into two federally governed territories – Jammu and Kashmir, and Ladakh.

Earlier this month, assembly elections were held in Jammu and Kashmir for the first time since the abrogation. But Ladakh continues to be a federal territory without legislative powers.

Individuals in Ladakh say this is cruel, and that they need their own staff. They worry about how quickly the region’s infrastructure is being expanded, which they claim is harming the region’s unstable environment.

Before beginning his hunger strike, Mr. Wangchuk and his supporters made the long journey from Ladakh to Delhi’s investment. They claimed that Ladakh’s greater independence under a constitutional provision known as the Sixth Schedule would help stop the abuse of natural assets.

After months of months of months of negotiations between locals in Ladakh and national government officials failing, they finally made their march on base.

At Delhi’s territories, the protesters were detained for days after which Mr Wangchuk began his hunger strike. He ended it on Monday, following the government’s promise that conversations may start immediately.

Mr. Wangchuk has made sure that the needs of the Ladakh people have remained a part of the popular media in India for weeks through his protests and interviews.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr. Wangchuk has a long record of challenging the status quo.

As a child, he studied for three years in Srinagar city (then the capital of Jammu and Kashmir state) where lessons were taught in English, Urdu and Hindi. In an interview, he recalled being the “butt of jokes” in class.

” In Srinagar, I was a silly child from Ladakh who could not communicate Hindi or English”, he said.

His observations in the 1980s led him to issue Ladakh’s educational program, which he claimed did not address local demands. He objected to the use of texts in an area where the majority of speakers Ladakhi speech were from English and Urdu.

” All the textbooks, even in early primary classes, came from Delhi. The examples included places of unknown cultures and settings like oceans, palm trees, monsoon rains, and ships, according to a statement on the website of a school he co-founded. These mysterious cases in foreign languages merely confounded Ladakhi children.

Since then, he has collaborated with local government and communities to make sure that the educational system meets the individual requirements of Ladakh’s kids.

His inventions have also been covered in the media.

Mr. Wangchuk studied electrical engineering after a family noticed his experiments with convex mirrors to brighten dark spaces and prepare meals.

In recent years, he has developed a low-cost clay house that maintains a temperature of 15C yet in -15C problems.

He also created an artificial flower in the shape of an snow stupa, a hemispherical structure typical of Buddhist cultures, to store rainwater for use in the late spring when farmers require it.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEarlier this year, Mr Wangchuk sat on a 21-day protest in the freezing cold “to remind the government of its promises to safeguard Ladakh’s environment and tribal indigenous culture”.

He was joined by thousands who fasted with him and held rallies.

When those demonstrations failed to produce the desired outcomes, Mr. Wangchuk walked to Delhi.

He has continued his demands in the money for the seventh schedule in Ladakh. This clause, which has been put into effect in the northern states of India, grants cultural populations exclusive authority to protect their interests in matters like natural resources and infrastructure. Ladakh has a lot cultural people.

” The sixth plan gives visitors not just a right but a duty to preserve their culture, forests, rivers and ice”, he told reporters.

Without legal protection, Mr. Wangchuk and his supporters claim that the brittle Himalayan ecology is in danger.

The government’s recent push to build up system in border areas raises these issues.

Ladakh, which edges both China and Pakistan, has a strategic significance for India.

The federal government has sanctioned many highways, power tasks and military-related facilities in Ladakh, which Mr Wangchuk says may damage the area, especially in the presence of consultation with local representatives.

” We do n’t oppose development. We want sustainable growth”, he said.

Special arrangement

Special arrangementAccording to Mr. Wangchuk and his supporters, Ladakh’s ecology means it ca n’t adhere to the development strategies of other Indian states. They claim that city dwellers are insensitive to the particular requirements of Himalayan regions.

” You do n’t get to see this in your cities but in Ladakh, there are proper winter, summer, and spring seasons, just like you read in books”, said Haji Mustafa, who had walked with Mr Wangchuk to Delhi.

Protesters have also voiced concerns that the locals did n’t get any benefit from the projects in Ladakh.

” Our natural resources are getting exploited. The unemployment rate is very high. Local businessmen are unhappy. So, who is this development for”? Mr Mustafa asked.

Tashi Gyalson, the leader of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, has received questions from the BBC.

Protesters vow to keep fighting until they have a say in what transpires in Ladakh.

Mr. Wangchuk expressed hope that a solution would emerge soon as the government agreed to resume discussions earlier this week.

” I hope the discussions will be conducted in mutual trust and will lead to a happy ending for everyone,” he said. And that I wo n’t have to march 1, 000 kilometers to the capital or sit on fast once more.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook