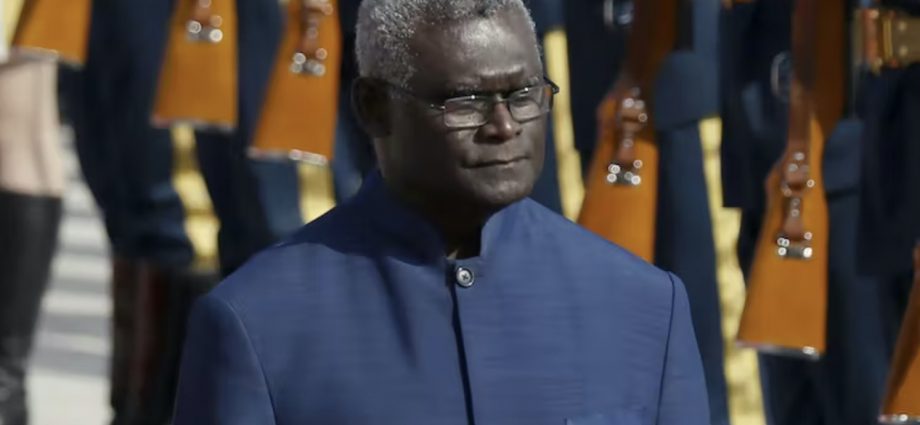

Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare will arrive in Australia on October 6 for talks with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. What should we expect from his visit?

Sogavare has had a tumultuous year, particularly as far as relations with Australia are concerned: in April, he signed a controversial security pact with China, the latter of which has been expanding its reach in the Pacific.

It was telling that one of Australian Foreign Minister Penny Wong’s first overseas missions after Labor won the May election was to the Pacific, including the Solomon Islands.

More recently, Sogavare blasted Canberra for making an “assault on our parliamentary democracy” and directly interfering in domestic affairs after the Australian government offered to help fund the upcoming election, to avoid postponing them to accommodate the 2023 Pacific Games.

Yet only a few weeks earlier, Sogavare also referred to Australia as the country’s “security partner of choice” and gave our PM a warm hug when they met. He even accepted the election funds after securing a one-year extension to his term in office. Support the 2023 Pacific Games – one of his top priorities – was banked too.

Sogavare is no stranger to political leadership — he’s been the prime minister of Solomon Islands four times since the mid-1990s. It’s a difficult job, and political allegiances in the island nation are fluid.

Sogavare has benefitted from generous Chinese aid and resource revenue. His Western friends worry that increasing Chinese investment could give China a strategic advantage and destabilize the delicate geopolitical balance in the region.

Of course, Honiara still benefits from generous aid from Australia and other donors. Australian assistance exceeds $150 million each year, in addition to defense cooperation. Sogavare has no intention of giving up diverse development investments; if he can, he’ll maximize all.

He’s a fiery orator and adept political operator. He regularly appeals to national pride, but when support wavers he can be assertive, even authoritarian. He switched the country’s recognition to China without waiting for advice from the Foreign Relations Committee, limited media scrutiny of his government, and withheld finances from unsupportive MPs.

A nationalist leader, Sogavare is wary of Australia and its motives. He fears Australia wants to control, not partner, with him. Feeling the political heat from the Australian government after his switch of recognition from Taiwan to China, he lashed out at Australia and others for undermining his government and failing to recognize its sovereignty.

A fractious relationship

His relationship with Australia has long been rocky. In 2006, when prime minister previously, he expelled the Australian High Commissioner over a dispute about a legal case against his attorney general.

Matters reached a low during a subsequent and related raid of his offices involving Australian police. He angrily threatened to chuck Australia out of the country. It’s unlikely Sogavare has forgotten or forgiven that chapter of history.

Nonetheless, times move on. At the departure of the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI) in 2017, Sogavare gave an emotional speech of gratitude for what the mission (and Australia) achieved.

He thanked Australia for police assistance late last year to help control rioting. The regional intervention brought calm, but Honiara still endured loss of life, looting and extensive property damage.

The inability of his police forces to control social unrest creates a political vulnerability. Sogavare signed the security pact with China to boost his response options for any future unrest and diversify aid and trade. This is in addition to the security agreement Solomon Islands has with Australia. The Chinese deal also benefitted government (and political) coffers.

Some believe the deal helped Sogavare fight off a motion of no confidence that followed the riots.

The Albanese government has acted quickly to calm the political waters stirred up by the Morrison government’s strong response to the China security pact and other festering irritants related to weak action on climate change and the AUKUS deal. One of the first bilateral visits Foreign Minister Wong made was to the Solomon Islands.

Like other Pacific leaders, Sogavare will leverage the tense geopolitical situation to his advantage. He’ll work to diversify, not deter, donor relations, even if at times it gets rather messy. To date the strategy has boosted assistance to Solomons by hundreds of thousands.

Harsh words thrown our way by Sogavare are not well matched by public sentiment. For the people of Solomon Islands, Australian engagement is welcome, including security assistance, generous aid, and the expanded labor mobility program.

Sogavare can be tough on Australia, but it’s a careful balancing act. He’ll want to maintain, even grow, labor market access, educational scholarships, and investments in Covid recovery and infrastructure.

There is mutual interest in keeping the region and the Solomon Islands stable.

For the upcoming visit, Australia will not apply pressure, but rather play the long game and advance an image of a patient and committed friend. The clear message will be that the door is open for dialogue and the relationship will endure beyond these tense times, and strengthen. Sogavare will likely also be measured and courteous as a guest of state.

There will be sweeteners. Australia will likely put additional offers of assistance on the table, which Sogavare will no doubt graciously accept. But that won’t bind him in the future. His attitude to Australia will remain prickly and wary.

The message from Sogavare is he’ll call the tune, even if it is discordant. The Solomon Islands’ opposition, and many back in his country, would prefer a less bellicose approach.

Like other regional leaders, Sogavare claims to be “friends to all, enemy to none.” That’s a nice way of saying: I can go elsewhere when pressured or need resources. But true friends take care not to undermine the foundations, integrity and longevity of a relationship.

This trip is an opportunity to strengthen the relationship through quiet diplomacy, with neither side shying away from critical issues of strategic interests, media freedom and climate action.

Meg Keen is Honorary Professor, Department of Pacific Affairs, ANU; Director, Pacific Island Program, Lowy Institute, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.