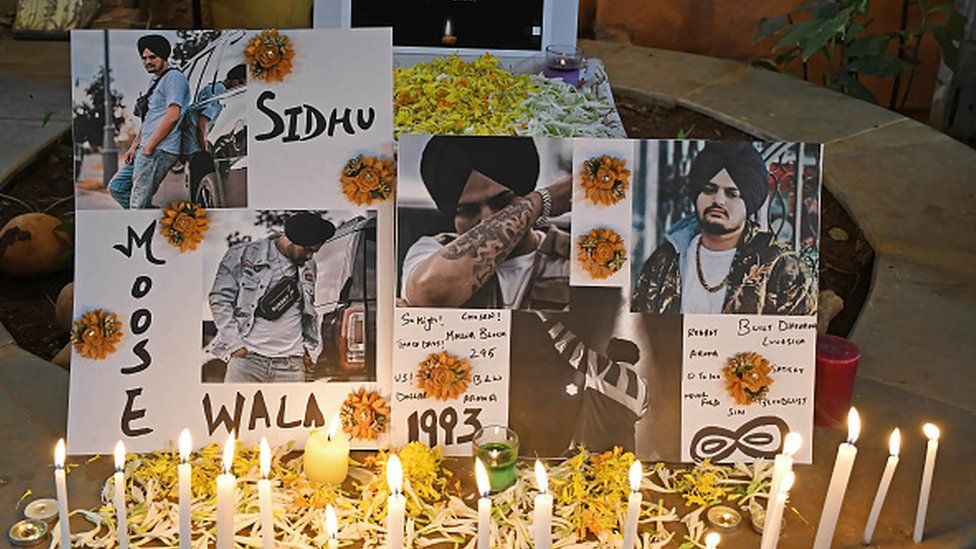

Sidhu Moosewala through Instagram

Sidhu Moosewala through Instagram It has been more than a month since rapper Sidhu Moose Wala has been shot dead in the northern Indian condition of Punjab. But he is still making head lines.

Some of this is because of the way he died and the ongoing police investigation .

But his music is also continuing to make surf.

In June, Moose Wala’s last music SYL was taken out of YouTube in Indian after the government stuck a legal complaint. The particular posthumously released track talks about decades-long question over sharing river water between Punjab and the neighbouring state of Haryana, while also touching on some other controversial subjects like Sikh militancy.

It’s fitted that his heritage of asking difficult questions continues even with his death.

Inside a career spanning simply four years, Moose Wala wrote a number of powerful lyrics that will explored the history plus current state associated with Punjab. Critics say the state has an unsavoury side, involving the gritty gangster culture, corruption and increasing unemployment and his music spotlighted that.

Their fans see him as a man who was engaged with interpersonal realities. But exactly what set him aside from his contemporaries was that he also offered a divergent eyesight of how Punjabis understand themselves and his concepts were often considered unsettling and incendiary.

His appreciation for guns plus attempt to force listeners into complex or even uncomfortable conversations : like SYL : made him the subject of intense scrutiny.

“There is no doubt that he was a man of contradictions, ” says Harinder Happy, a research scholar who has researched Punjab closely. “But his style talked to the times and also to living in a post-modernist society where people have the right to assert their particular identity the way they realize it. ”

Moose Wala seemed to be deeply rooted to his home and village in a state where thousands are looking to immigrate in order to foreign shores in search of a better life.

Getty Images

“He was many things, yet above all he has been deeply connected with the ecology of his village, ” says Pritam Singh, professor of economics on Oxford Brookes University, who has followed Moose Wala’s music carefully.

The singer was created as Shubhdeep Sidhu in an upper-caste Jatt-Sikh family. After studying engineering, he moved to Canada, where thousands of Sikhs possess emigrated.

It was there that he began their music career, releasing his debut album PBX 1 in October 2018 under the stage name of Sidhu Moose Wala : or “Sidhu associated with Moosa”, his town.

The singer preserved a distinct hip-hop language, from clothes to style, which made him an instant hit in the global stage. Their music at the time seemed to be typically macho – as rap songs often is : and swaggered over the edge of violence. Unapologetically belligerent, he or she sang about his fondness for weapons, boasted about their caste and provided details of a put-down of his foes.

“Moose Wala could’ve lived anywhere he wanted. But this individual chose his community, his parents great people, ” Mr Happy says. “He not just held onto his village identity but also sought to elevate it, despite the complexities. ”

Mansa district, where Moose Wala’s village is located, is widely seen as a backward region – it has one of the highest farmer suicide rates in Punjab and high unemployment levels and a serious groundwater crisis.

“People have a tendency want to be identified with the region – they wish to leave and never come back, ” Mr Joyful explains. “But Moose Wala was different. He took pride in his roots great music urged audience to proudly acknowledge the village as home. ”

This is captured most strongly in Tibeyan De uma Putt (Son from the sand dunes), signifying the semi-arid scenery of the region. “We do not belong to noble families/ Brought-up within the village and townships/ I don’t have any presence of my own/ Yet, influential individuals fear me, ” the lyrics say.

Getty Images

Song right after song, Moose Wala evoked the draw of village existence, urging his listeners to embrace an agrarian lifestyle. Within Bambiha Boley, he or she highlighted the beauty of conventional folk music; in Never Fold, this individual turned to stories associated with Robin Hood-like folks heroes who swindled the rich to help the poor.

Mr Joyful says that Moose Wala came to embody the aspirations from the entire region, assisting people cope and take pride in their identification.

“And he had been accessible – anyone could meet your pet and he loved their fans. The vocalist often shot the majority of his videos in his village, featuring their family, which made him even more relatable, ” he provides.

Over time, Moose Wala’s music also became more socially, culturally and politically conscious.

The most iconic of these was 295 – a song about freedom associated with speech in India. The title refers to Section 295 from the Indian Penal Code, which penalises activities “intended to outrage religious feelings”.

Within 2020, his song on India’s good agricultural laws grew to become an anthem for protesting farmers. The lyrics to these songs – “This is none other than the Punjab, which takes revenge with an open challenge” – were hailed for embodying the ability of resistance, yet critics said these were problematic and glorified violence.

Getty Images

Moose Wala never really stopped becoming controversial – this individual continued to chuckle at his opponents and pose along with guns.

“But over time, he relocated away from casteist metaphors and his engagement with weapons became a lot more measured, ” Prof Singh says.

This particular thematic shift, he adds, is central to the singer’s character. “That’s because Moose Wala’s story is also one of personal evolution. And unless we all understand that, we are unable to understand why he was so popular. ”

The contradictions don’t finish there.

Both Prof Singh and Mister Harry point out that will unlike other artists, Moose Wala’s music lacked the lovemaking explicitness often related to hip-hop and especially rap and his music by no means objectified or denigrated women.

In Beloved Maa – the song dedicated to his mother – Moose Wala does not eschew overt sentimentality. Rather, he embraces this, Prof Singh states.

“It is impressive that a man who will be accused of being masochistic and violent is really saying ‘mother, We are like you’. And he captures the technicalities so beautifully — one moment he admits that he’s hot because the sun but also he is soft like her. ”

In his memoir, popular United states rapper JayZ wrote: “Rap is built to manage contradictions. ” Plus Moose Wala’s music almost always carried multiple meanings, from politics leanings to the messiness of identity plus questions that often escape simple explanations.

Mr Happy says that music was Moose Wala’s way to hold difficult conversations, to back and to assert their identity.

“His music’s most persistent subject matter has been what it means to be Punjabi and how identification cannot be a monolith. Every album, every single song, and every word is dedicated to showing this truth, ” he adds.

This inquiry into the Punjabi identity was also rooted in his insistence that life in Punjab was more than just assault and drugs. Simply by blending folk songs with slick beats and sounds, Moose Wala was able to create rhymes that tackled the lives of Punjabis in ways they will understood.

“It was this rural rootedness of his which usually resonated with people therefore deeply, ” Prof Singh says.

Over anything, Moose Wala, Mr Happy states, put forth an exciting idea that there was freedom available within music.

“And being controversial will be inevitable when you ask tough questions. ”