Picryl

PicrylShapurji Saklatvala does not seem to be the name that most people associate with record books. The child of a cotton merchant, a part of India’s extremely wealthy Tata clan, has really a story, as with any great old-fashioned tale.

At every turn, it seems that his career was one of continual struggle, rebellion and persistence. He shared both the title of his privileged cousins, nor their life.

In contrast to them, he would continue to lead the Tata Group, which is now one of the biggest business empires in the world and is the owner of renowned British brands like Tetley Tea and Jaguar Land Rover.

Instead, he emerged as a resolute and powerful politician who fought for India’s independence in the British Parliament, which was its coloniser, and yet clashed with Mahatma Gandhi.

But how did Saklatvala, born into a community of businessmen, follow a route so different from his family? And how did he establish himself as one of the country’s earliest Eastern MP? The answer is as difficult as Saklatvala’s connection with the his personal home.

Getty Images

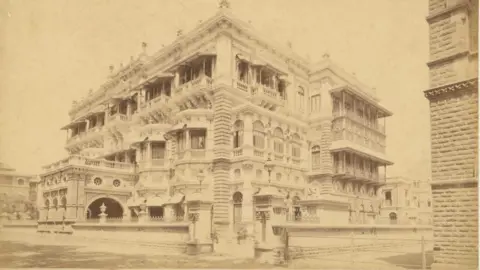

Getty ImagesSaklatvala was the brother of Dorabji, a cloth trader, and Jerbai, the youngest child of Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata, who founded the Tata Group. When Saklatvala was 14 years old, his family moved into Esplanade House in Bombay to live with Jerbai’s brother ( whose name was also Jamsetji ) and his family.

When Saklatvala was younger, his parents split up, and the younger Jamsetji rose to prominence as the primary father figure in his career.

” Jamsetji always had been particularly proud of Shapurji and saw in him from a very early age the choices of great possible, he gave him a lot of focus and had great faith in his abilities, both as a child and as a man”, Saklatvala’s child, Sehri, writes in The Fifth Commandment, a history of her parents.

But Jamsetji’s fondness of Saklatvala made his elder son, Dorab, resent his younger cousin.

” As boys and as men, they were always antagonistic towards each other, the breach was never healed”, Sehri writes.

It would eventually lead to Dorab curtailing Saklatvala’s role in the family businesses, motivating him to pursue a different path.

Saklatvala was also profoundly influenced by the destruction brought on by the bubonic plague in Bombay in the late 1890s, aside from family dynamics. He observed how the poor and working classes were disproportionately affected by the epidemic while those in the upper echelons of society, including his family, were largely spared.

During this time, Saklatvala, who was a college student, worked closely with Waldemar Haffkine, a Russian scientist who had to flee his country because of his revolutionist, anti-tsarist politics. Haffkine developed a vaccine to combat the plague and Saklatvala went door-to-door, convincing people to inoculate themselves.

According to Sehri,” their outlooks shared many things, and unquestionably this close association between the idealist older scientist and the young, compassionate student must have helped to form and crystallize Shapurji’s convictions.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHis friendship with the waitress Sally Marsh, who he would marry in 1907, was another significant influence. Marsh was the fourth of 12 children, who lost their father before becoming adults. Everyone in the Marsh family worked hard to make ends meet, so it was a difficult situation.

However, the well-heeled Saklatvala was drawn to Marsh, and during their courtship, he was given a taste of the hardships of Britain’s working class through her life. During her father’s school and college years, Sehri writes that the sacrifices of the Jesuit priests and nuns, under whose guidance he went, had an impact on her father.

So Saklatvala re-enters politics in the UK in 1905 with the intention of helping the underprivileged and the marginalized. He joined the Labour Party in 1909 and 12 years later, the Communist Party. He believed that only socialism, and not any imperialist regime, could end poverty and give people a say in governance, and that only the working class could do so in India and Britain.

Saklatvala’s speeches were well received and he soon became a popular face. He was elected to parliament in 1922 and would serve as an MP for close to seven years. During this time, he advocated ferociously for India’s freedom. His views were so fervent that a Conservative Party member from Britain viewed him as a dangerous “radical communist.”

During his time as an MP, he also made trips to India, where he held speeches to urge the working class and young nationalists to assert themselves and pledge their support for the freedom movement. He also helped organise and build the Communist Party of India in the areas he visited.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHis vehement opposition to communism frequently clashed with Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent strategy to defeat their shared adversary.

In one of his letters to Gandhi, he wrote,” Dear Comrade Gandhi, we are both erratic enough to allow each other to be rude in order to freely express oneself correctly,” and then went on to express his dissatisfaction with Gandhi’s refusal to support his” Mahatma” ( a revered person or sage ), and he proceeded to mince no words about his discomfort with Gandhi’s non-co-operation movement and his permission for people to refer to him as”

Although there was never a breakthrough, the two remained cordial and unwavering about their shared goal of overthrowing British rule.

Saklatvala was prohibited from visiting his country in 1927 because of his fiery speeches in India. In 1929, he lost his seat in parliament, but he continued to fight for India’s independence.

Up until his death in 1936, Saklatvala was a significant figure in British politics and the Indian nationalist movement. In a cemetery in London, he was cremated, and his remains were interred with those of his parents and Jamsetji Tata, bringing him once more together with the Tata clan and their legacy.