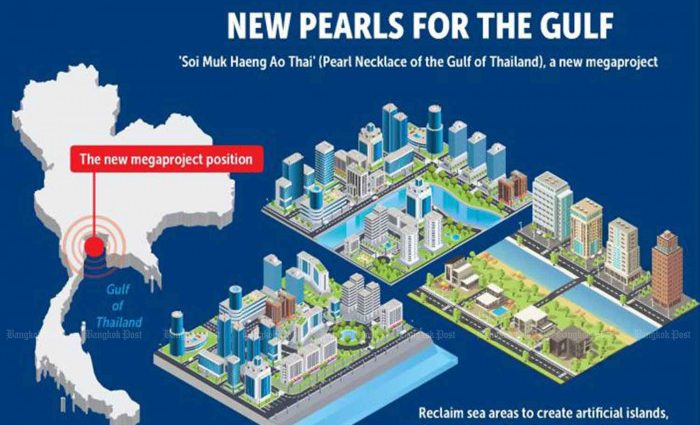

The Pheu Thai Party’s plan to build a seawall comprising nine artificial islands in the Gulf of Thailand, which would stretch from Bang Khunthian district in Bangkok to Chon Buri, has drawn protests from critics, many of whom are concerned about the project’s impact on the environment.

The plan was one of the ideas floated by former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra at his high-profile dinner talk, “Vision for Thailand 2024”, which was held in Bangkok on Aug 22.

According to Plodprasop Suraswadi, a former deputy prime minister who is now serving as the chairman of Pheu Thai’s environment policy committee, the seawall will help protect Bangkok and its surrounding provinces in the Central Plains from flooding caused by rising sea levels.

In addition, he said, the islands could be developed into green, smart communities that are powered by wind turbines and solar panels, providing more space for residents and business.

PHEU THAI’S PLAN

Mr Plodprasop said Pheu Thai has been studying various flood prevention measures, including the seawall project, to protect the capital and its surrounding areas for a long time.

The project was even listed as a government priority scheme by the Yingluck Shinawatra administration, he said.

According to the project’s blueprint, each island will have an area of about 50 square kilometres.

The islands will be located about one kilometre off the coast in the Gulf of Thailand and linked to each other by a series of dikes. A bridge will also be built to connect the islands to the mainland.

Viewed from above, the islands will form the letter of the Thai alphabet, “Ko Khai”.

The project is likely to be carried out by private investors, who will be granted a 99-year concession to develop the islands for various purposes, Mr Plodprasop told the media.

At the end of the concession, however, the islands will be handed over to the state.

“The whole country will benefit from the project, as it will not only protect the capital and other provinces in the Central Plains from flooding, but also stimulate the economy,” he said.

Mr Plodprasop said that if approved, the project will be the country’s most expensive project to date. It will also take more than 20 years to finish, he said. As such, a strong political commitment is needed if the project is to succeed, he said, adding if the project is approved by the government, it would become an enormous boon for the economy.

Similar projects in the United Arab Emirates, the Netherlands, Hong Kong and Singapore could be studied as a model for Thailand’s biggest land reclamation project, he said.

Mixed reactions

Petch Manopawitr, a member of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), said land reclamation projects go against the growing trend of using nature-based solutions to limit the impact of climate change.

Physical construction won’t win against nature, so governments across the world are turning to nature-based solutions, which focus on improving local ecosystems and optimising existing infrastructure to deal with the adverse effect of rising sea levels, he said.

Bangkok, which is located on a low-lying plain that is prone to seasonal flooding, especially during the rainy season, would benefit from improved city planning, he said.

For example, the capital needs more water retention zones in public parks and the city’s canals need to be dredged and deepened to increase their capacity, he said.

“It is a pity that a lot of good proposals put forth by civil society groups have gone nowhere because of the lack of political support,” said Mr Petch, adding when it comes to environmental issues, government officials often bet on the wrong horse.

“For instance, whenever the North gets flooded, politicians would rally behind the proposed Kaeng Suea Ten Dam in Phrae, despite many studies concluding that the project is not worth investing in.

“They believe the dam will be the silver bullet that ends all of the problems, often making outrageous claims about the project’s benefits for the people,” he said.

The IUCN member said long stretches of the coastline in the Gulf of Thailand contain mangrove forests, which are not only home to countless juvenile marine animals, but also productive fishing grounds for local fishermen.

Furthermore, these mangrove forests are regarded by the Bird Conservation Society of Thailand as crucial nature reserves, as they are important transit points for many migratory birds. “Any mega-construction in the area will destroy their natural value,” Mr Petch said.

Meanwhile, Thon Thamrongnawasawat, deputy dean of Kasetsart University’s Faculty of Fisheries, doubts if the project will ever be realised.

“It is not an easy undertaking, as this megaproject requires a huge budget,” he said.

Not a novel idea

Mr Thon said that the proposal is similar to the previous government’s plan to build a maritime link across the Gulf of Thailand to link Chon Buri to Prachuap Khiri Khan, which has yet to go anywhere.

He also raised concerns about the government’s plan to use land reclamation projects abroad as a model for the seawall project. “Different countries have different landscapes and geographical features. What was successfully done in the Netherlands might not be applicable in Thailand,” he said.

In Singapore, for instance, the project could be carried out with minimal impact to society because the new islands are situated in a maritime reserve.

Banjong Nasae, chairman of the Rak Thale Thai Association, said the project would have a big impact on the region’s biodiversity.