The headline-grabbing maritime boundary deal announced between Lebanon and Israel this week produced several winners and losers. Determining who is who is another matter.

Leaders in each country claimed victory after US President Joe Biden unveiled the agreement, while opposition groups on both sides accused their own governments of conceding national wealth. There are also questions about the deal itself and whether it will survive the political storms that are coming.

So, before finalizing the score, we must first identify what was, and remains, at stake.

The long-standing dispute was over a maritime border serving two key purposes: security, and delineation of the countries’ exclusive economic zones (EEZs).

On the security side, Israel clearly came out on top. Israel will maintain control over a line that starts 5 kilometers from the coast and stretches into territory that Lebanon considers its own. Lebanon tried to push this line south, but Israel resisted, concerned that a shift would give the Lebanese direct access to Israel’s north.

The tally on economics is more mixed.

Until the early 2000s, when Israel and Egypt began discovering gas reserves in their territorial waters, there had been little economic activity in the eastern Mediterranean. Once gas was found, Lebanon began conducting seismic explorations of its own, which hinted that it too had gas reserves that were commercially viable.

Exploration rights to the most promising Lebanese blocks – 4 and 9 – were awarded to the French oil giant Total in 2018.

Total drilled Block 4, off the coast of Beirut, in 2020, but came up dry. Total said it would not drill Block 9, whose southern border was disputed by Israel, without Israel’s consent – which in turn required having Hezbollah on board.

Not long ago, Hezbollah’s buy-in for a deal with Israel would have been inconceivable. But the free-falling Lebanese economy forced Hezbollah to bend.

Lebanon is a rentier state. Oligarchs use its resources to offer their partisans social services, including government jobs, health care and pensions. With the state going bankrupt, millions of Lebanese find themselves without a social safety net. Some have started to rely on Hezbollah’s services, which are also stretched to breaking point.

For instance, the Great Prophet Hospital, Hezbollah’s main health-care facility in Beirut, has been unable to cope with an ever-growing roster of patients. The hospital can barely keep the lights on, and medicine is in such short supply that those who live with chronic diseases, such as diabetes, have few options. Lebanon has already run out of affordable insulin.

As Lebanon falls apart, Hezbollah is being squeezed. Lebanon’s Shia, from whom it draws its support, are hurting, while the party – and its impoverished sponsor Iran – can do little to ease the suffering.

In the hopes of producing gas to help mitigate Lebanon’s economic disaster, Hezbollah sued for settlement of the maritime border issue to allow Total to dig up Block 9.

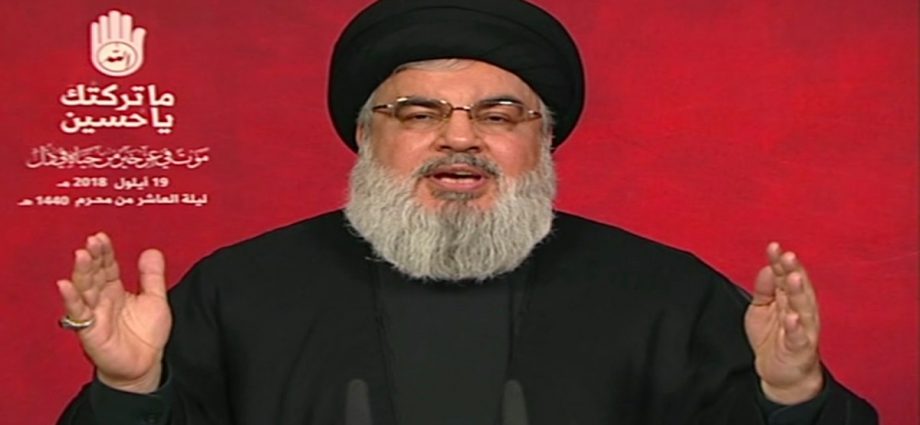

But before the party’s chief, Hassan Nasrallah, went on national television on the eve of the deal’s announcement to metaphorically drink the poison, he’d flown a couple of drones into Israeli airspace in the summer, presumably targeting Israel’s Karish gas field.

Nasrallah pretended that he had put Israel on notice: He would hit Karish if Israeli production began before a deal with Lebanon was reached. In other words, Hezbollah was threatening Israel with war to force a deal.

Everyone, especially Israel, knew Hezbollah couldn’t drag Lebanon into war in its current state. Yet Israeli officials likely believed they could extract some concessions from Lebanon, such as the demarcation of borders between them, both on land and at sea.

Hezbollah wanted a compromise, but not one that recognized Israel and demarcated borders in a way that would end all territorial disputes between the two sides. Hezbollah, after all, exists to fight Israel. Thus terrestrial border demarcation was taken off the table.

In its place came a maritime boundary that stopped 5km short of shore, leaving most of Block 9’s Qana field in Lebanese hands.

If gas is discovered in Qana, Lebanon will receive 83% of its revenue, while Israel will get 17%. In previous scenarios offered by the United States, Israel was given 45% of the disputed area.

While assessing Qana’s reserves has to wait until later stages of exploration, the Israeli Ministry of Energy predicts that Qana holds just US$3 billion worth of gas. With $68.9 billion in external debt, Qana’s potential won’t move the economic needle in Lebanon. Unless Qana proves to be a mega field, or unless other fields are suddenly discovered, Lebanon’s claim of economic victory in maritime talks over Israel will prove misplaced.

But if Qana surprises with big reserves, or if other fields with sizable amounts of gas are discovered, Israel would have shot itself in the foot by taking the US-brokered deal.

Moreover, the temporary nature of the deal could allow Israel to ask for reconsideration, or it could crumble completely. The deal itself is not a treaty between two countries, but a US document and deposit of maps with the UN (the second such deposit since 2009).

None of this went through a ratification process – at least not in Lebanon. In Israel, the cabinet voted but the Knesset did not, and an Israeli cabinet vote could be reversed by a future cabinet vote.

Finally, if Israel’s opposition leader, Benjamin Netanyahu, who trashed the deal during its run-up, becomes prime minister again on November 1, Israel could withdraw before it’s clear how much gas Qana holds, if any.

No matter how all of this plays out, this much is certain: Declarations of victory, by either side, are premature.

This article was provided by Syndication Bureau, which holds copyright.