In the girl four fragile yrs, Yasmin has lived a life of uncertainty, unsure exactly where she belongs.

Born in the refugee camp within Bangladesh, she is not able to return to her our ancestors village in Myanmar. At the moment, a dingy room in India’s capital, Delhi, is home.

Like hundreds of thousands of Rohingya people – an ethnic minority in Myanmar – Yasmin’s parents fled the country in 2017 to flee a campaign of genocide launched by the military.

Many fled to neighbouring nations like Bangladesh and India, where they live as refugees.

5 years on, Rohingya Muslims – the world’s largest stateless population, according to the UN – remain in limbo.

Yasmin’s father, Rehman, was a businessman in Myanmar. As the military brutally attacked individuals, he became among 700, 000 Rohingyas who fled inside a mass exodus.

After walking for the, Rehman and his spouse Mahmuda made it towards the refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar, the in south-eastern Bangladesh that is close to the border with Myanmar.

Here the couple lived in cramped conditions. Food shortages were common and they lived away from rations from charitable organizations.

Per year after they reached Bangladesh, Yasmin was born.

The Bangladesh government has been pushing to get Rohingya Muslims to come back to Myanmar. Thousands of refugees have been moved to a remote island called Bhasan Char, which usually refugees describe as an “island prison”.

Rahman felt that leaving Bangladesh might help his kid have a better future.

And so within 2021, when Yasmin was just a few years old, the family crossed more than into neighbouring India.

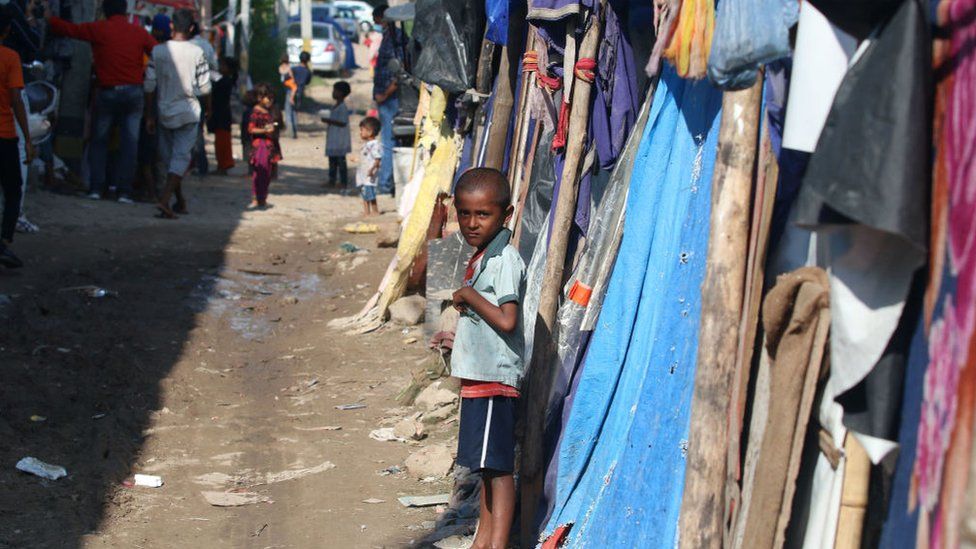

Estimates vary, yet refugee organisations think there are between 10, 000 and 40, 000 Rohingya refugees in India. Many have been in the country considering that 2012.

For a long time, the Rohingyas right here have lived the modest life appealing to little controversy. Yet after a federal ressortchef (umgangssprachlich) tweeted this month that the refugees will be provided with housing, facilities and police security, their presence in Delhi made refreshing headlines.

Getty Pictures

Hours later on India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government denied it had offered these facilities to Rohingya Muslims, instead describing them as “illegal foreigners” who ought to be deported or delivered to detention centres.

This apparent change of tone has left families like Rehman’s disillusioned and eager.

“The future of my kid seems bleak, inch he said, as he sat on a rickety wooden bed frame without mattress.

“The government of India doesn’t want us either… but I had created rather they killed us than deported us to Myanmar. ”

No country is willing to consume the hundreds of thousands of Rohingyas. Last week Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina told the particular UN High Commissioner for Human Legal rights, Michele Bachelet, which the refugees in her country must go back to Myanmar.

However the UN says its unsafe for them to do this because of the conflict within Myanmar. In Feb 2021, the Myanmar junta – that are accused of offences against the Rohingyas — took control of the nation in a military hen house.

Hundreds of Rohingyas have made perilous journeys by sea to countries for example Malaysia and the Philippines to escape the atrocities perpetrated by the zirkel.

The number of political refugees in camps within Bangladesh has grown in order to close to one million. Half of them are kids.

Like Rehman, Kotiza Begum also fled Myanmar within August 2017, walking for three days without any food.

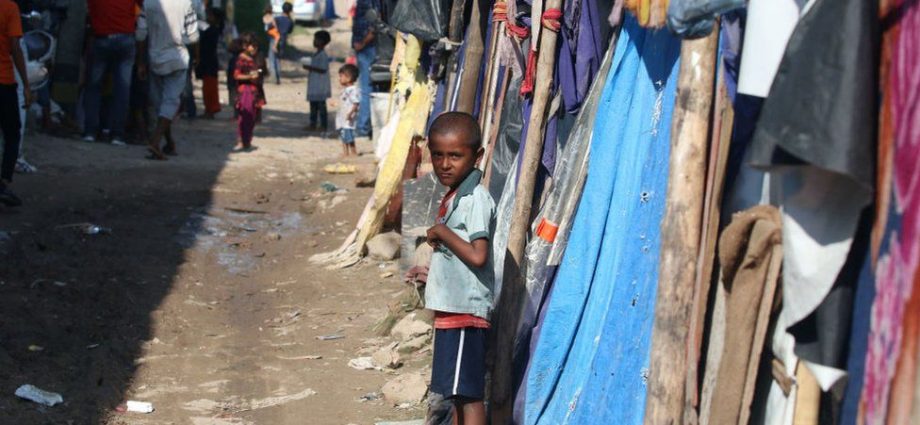

The lady and her 3 children live in just one room in a camping in Cox’s Bazar. They have a plastic-type material sheet as a roofing, which offers poor protection from rain during the monsoons.

The horrors of what the lady left behind in her homeland are still clean in her mind.

“The military entered our house plus tortured us. Because they opened fire, we all ran. Children were thrown into the water. They just slain anyone in their paths. ”

Like others in the camps, Kotiza is reliant on food rations from NGOs and charities, which are generally limited to the basics such as lentils and rice.

“I can not feed them the meals they want, I can’t provide them with nice clothes, I can’t get them proper medical facilities, ” the girl says.

Kotiza says she occasionally sells her rations to buy pens on her children to write with.

According to a recent EL assessment, cuts within international funding have added to the challenges for a population that will remains “fully dependent on humanitarian help for survival”.

The particular UN said the particular refugees continue to struggle to get nutritious food, adequate shelter and sanitation, and in order to work.

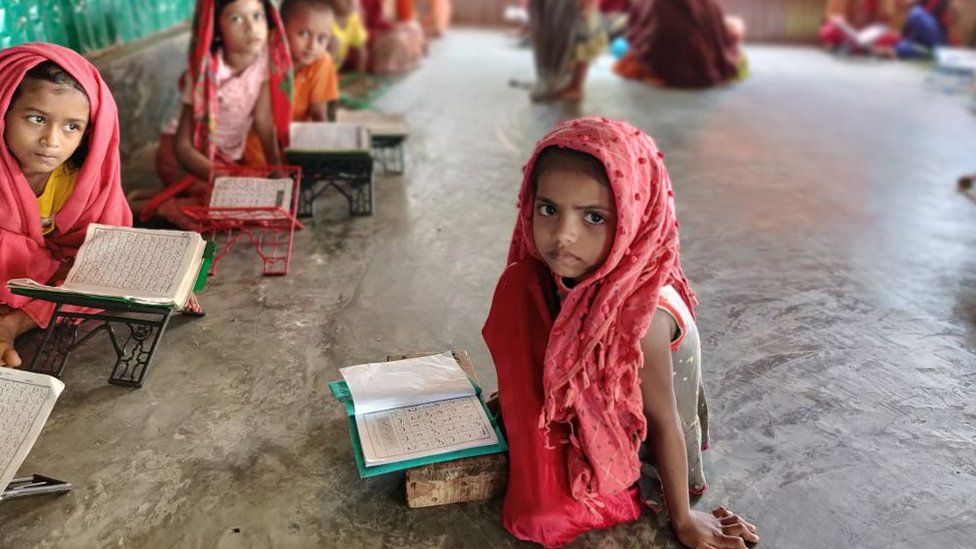

And training – one of Kotiza’s biggest priorities for her children – is also a big challenge.

There are concerns of a lost generation, who seem to aren’t getting good schooling.

“The children go to college everyday, but body fat development for them. We don’t think they’re getting a good education, ” Kotiza says.

Children living in camps in Cox’s Bazar are taught the particular Myanmar curriculum – the curriculum of their home country – rather than the one taught within schools in Bangladesh.

While advocates of the programme state it’s to prepare learners for a return to their own homeland one day, other people fear it’s a way to prevent the Rohingya asylum population from adding with Bangladeshis.

“If they are educated, they can have beautiful life. They can earn intended for themselves and live happily, ” states Kotiza.

Getty Images

It’s a sentiment discussed back in Delhi by Rehman, as he cradles four-year-old Yasmin in the arms.

“I dream of giving the girl a proper education plus a better life, yet I cannot, ”

As Rohingyas all over the world mark the 5th year since fleeing genocide, they nevertheless hope they will get justice – a case filed against the Myanmar military is still waiting around to be heard at the International Court associated with Justice.

Yet more than that they dream of being able to return house.

Until items are safe for them to do this, refugees like Rehman are pleading with all the world for more assistance and compassion.

“I am not here to take, I’m here in order to save my life. ”

-

-

24 August 2019

-