Delhi, BBC News

Srinagar, Kashmir

UGC

UGCShabir Ahmad Dar, a native of Kashmir-administered India, has been selling sarong blankets for more than 20 years.

In Mussoorie, a valley community in Uttarakhand, his clients enjoy wearing his intricately embroidered lightweight hats.

The blankets represent comfort to his customers. They serve as a metaphor for house, with its classic designs layered with background, and a sign of Dar’s Kashmiri personality.

The exact identity is currently perceived as a curse.

Users of a Hindu right-wing party, who were apparently angry about the shooting of 26 people at a popular tourist location in Kashmir last year, apparently attacked and harassed Dare along with another seller. Islamabad refutes the claim that India is to blame Pakistan for the assault.

As the men ransack their stall, which is located on a busy street, the men are seen thrashing and hurling abuses at Dar and his friend on a picture of the abuse.

They told us to leave town and not show our faces again, according to Salaam, and they blamed us for the assault.

He claims that there are still thousands of dollars value of his products. ” But we are too afraid to go back.”

Authorities on Wednesday made the three men their arrests and released them a few hours after after charging a good and asking them to “apologise” to Salaam and his partner as outrage unfold.

Dar and dozens of other Kashmiri jacket dealers, who have resided in Mussoorie for years, have already left by that time.

Reuters

ReutersSome survivors of the new Pahalgam attack, which was the most deadly to target civilians in recent years, claimed that the militants specifically targeted Hindu men, causing outrage and anguish in India, with politicians from all political parties calling for strict measures.

There have been more than a few reports of Kashmiri contractors and students facing abuse, denigration, and threats from right-wing organizations, as well as from their own classmates, customers, and neighbors. Online video of students being chased out of their homes and brutally beaten on the roads have exploded.

One of the victims, whose father was killed in the violent attack, made an appeal to the public on Thursday to refrain from attacking Muslims and Kashmiris. We just want harmony, she said, and we want peace.

However, health issues have forced some Kashmiris, like Dar, to flee their homes.

Ummat Shabir, a medical student in Punjab state, claimed last week that some neighborhood people had accused her of being a “terrorist who should be thrown out.”

She claimed that her classmate’s vehicle forced her to leave the same day because he discovered her to be a Kashmiri. We had no other choice but to return to Kashmir after three weeks. We had to leave.

Ms. Shabir is now residing in her home, but some people find it difficult to feel safe away.

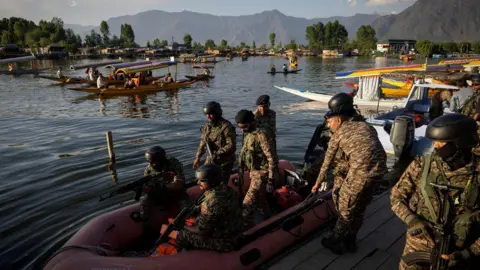

Safety forces in Kashmir have detained thousands of people as the search for the attackers of the attack next week progresses, shutting down more than 50 tourist destinations, dispatched more army and armed forces, and blown up some homes belonging to suspected militants ‘ families who they claim had “terrorist affiliations.”

The assault has sparked discomfort and anxiety among citizens, many of whom have referred to the actions as” collective abuse” against them.

Without going into detail about the evictions, Jammu and Kashmir Chief Minister Omar Abdullah said, “don’t let stupid people become collateral harm. Mehbooba Mufti, the former chief secretary, even criticized the evictions, warning the government to differentiate between “terrorists and residents.”

We are the first to bear the brunt of tension, according to the statement. Another pupil, who wanted to remain anonymous, told the BBC,” But we are still treated as defendants and expected to put our life on hold.”

Reuters

ReutersShafi Subhan, a blanket owner from the area’s Kupwara area who also worked in Mussoorie, claims that the reaction is much worse this day.

In his 20 years of operating it, Subhan claimed to have never been a victim of a common threat, not even after the Pulwama district terror attack in 2019 that resulted in the deaths of 40 paramilitary police officers.

Despite being hundreds of kilometers aside, Mussoorie still felt like home to him. It was where he found harmony. He claimed that he and his clients, who arose from all over the nation, shared an mental connection.

Folks always treated us well, and they always wore our clothing with such joy,” Subhan recalled. No single arrived to help on that day, though, because our acquaintances were attacked. The general public simply stood and watched. They were actually hurt, but physically it hurt them a lot more.

Peace has long been delicate in Kashmir back home. In the region under Indian control for more than three decades, an armed rebellion has persisted, killing thousands of lives, and both India and Pakistan claim the place in full but initiate separate elements.

Civilians who claim to be trapped in an endless purgatory that feels particularly suffocating whenever relationships between India and Pakistan come under pressure are caught in between.

Some claim that there have been major security and communication clampdowns in the region and waves of abuse and violence against Kashmiris in the past following military clashes between the countries.

EPA

EPAAuthorities point to improved facilities, tourism, and expense as indicators of greater stability in recent years, especially since 2019, when Article 370’s exclusive legal status was removed.

However, there are still arrests and safety measures, and critics claim that peaceful has been brought about by civil liberties and democratic freedoms.

Even though violence has declined in the last ten and a half years, visitors are always the target of fear, according to Anuradha Bhasin, managing director of the Kashmir Times papers. They must always provide evidence of innocence.

Kashmiris poured onto the streets, holding candlelight vigils and protest marches, as the news of the killings spread last week. A day after the attack, a complete shutdown was observed, and newspapers published black front pages. Abdullah formally apologised, saying that he had “failed his guests.”

Ms. Bhasin asserts that the Kashmiri backlash against these attacks is not new; however, there has also been similar demonization in the past, but on a smaller scale. No one there condones civilian killings because they are too well aware of the pain of losing loved ones.

She adds, however, that it’s unfair to impose the burden of proof of innocence on Kashmiris when they have already become victims of hate and violence. Many of the people who are already insulated from the rest of the nation would just become more afraid and feel alienated by this.

Reuters

ReutersBeing a member of India’s Muslim population, Kashmiris are “particularly vulnerable as they are seen through a different lens,” writes Mirza Waheed, a Kashmiri novelist.

The saddest part is that many of them will endure the humiliation and injustice, lay low for a while, and wait for this to pass because they have a life to live.

No one in Kashmir’s Shopian, whose home was bombed by security forces last week, is more familiar with Mohammad Shafi Dar, a daily wage worker there.

Five days later, he is still picking up the pieces.

Dar, who now resides with his wife, three daughters, and son, said,” We lost everything. We don’t even have cooking utensils, the statement goes.

He claims that his family is unaware of the location of their other 20-year-old son, whether or not he has enlisted in militancy or is even alive or dead. His parents claim that the college student left home last October and never came back. They haven’t spoken since then.

” Yes, but we have been punished for his alleged crimes.” Why”?