Ten years after becoming prime minister, Narendra Modi is aiming for a historic third term – what makes him India’s most prominent leader in decades?

Many voters feel things have got better since he took office in 2014, but will people who are struggling back him in the country’s general election?

In Mr Modi’s constituency in the northern city of Varanasi, saree weaver Shiv Johri Patel says he’s got many worries – but he’s clear who’s getting his vote.

“Mr Modi has done great work. We haven’t seen poor people getting so many welfare benefits under any other government,” he says.

Mr Patel says his sons can’t find jobs and local middlemen have cheated him out of a federal government welfare payment – but he doesn’t blame the prime minister.

“It doesn’t matter if I get what I’m owed or not, I will still vote for him,” he told the BBC.

Varanasi goes to the polls in the last round of voting before results day on 4 June.

At 73, Mr Modi remains a massively popular yet polarising figure, both in India and abroad.

Supporters claim he is a strong, efficient leader who has delivered on promises. Critics allege his government has weakened federal institutions; cracked down on dissent and press freedom; and that India’s Muslim minority feels threatened under his rule.

“Mr Modi has very staunch admirers and very strong critics. Either you like him or you dislike him,” says political analyst Ravindra Reshme.

Opinion polls have put Mr Modi comfortably ahead of rivals and his party is widely expected to form India’s next government. (Caveat: polls have been wrong before and voters can deliver unpleasant surprises – even for popular leaders).

He has set a tough target for his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) – winning 370 seats out of 543 in parliament, up significantly from 303 in 2019. This would mean not just retaining northern states the party swept last time but also gaining in traditionally tougher states for the BJP in the south.

Brand Modi

As he targets a supermajority, Mr Modi is his party’s biggest draw.

His face can be found everywhere – plastered on bus stops, billboards and newspaper adverts, or addressing televised election rallies.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

When India hosted the G20 summit last year, Delhi was awash with posters of him welcoming world leaders. The event is held according to a rotating presidency, but the publicity campaign made it seem as if it was due to Mr Modi’s efforts.

“Mr Modi turned it into a mega-event. In many ways, he has an understanding of what an event is about and how it should be used,” brand-building expert Santosh Desai told the BBC earlier this year.

Mr Modi and his team have an excellent understanding of branding and narrative-control – he is highly visible but rarely anywhere journalists or citizens can ask him tough questions. He has never held a press conference in India since becoming prime minister, while the interviews he gives are rare – and he is rarely challenged.

RK Upadhya, a political analyst, says to become prime minister, Mr Modi had to overcome an image of him in the media “as someone who was responsible for the Gujarat riots”. A Supreme Court-appointed panel later found no evidence that Mr Modi was complicit in the 2002 violence when he was the state’s chief minister. More than 1,000 people were killed, mostly Muslims.

“So I think when he came to Delhi, he wanted to show [the media]: ‘Look, I don’t need you. I can connect with people without you’,” Mr Upadhya says.

And connect he does: the septuagenarian is the world’s most-followed politician on Instagram, and has 97.5 million followers on X (formerly Twitter). And it’s not just digital – he also shares his thoughts in a monthly radio programme.

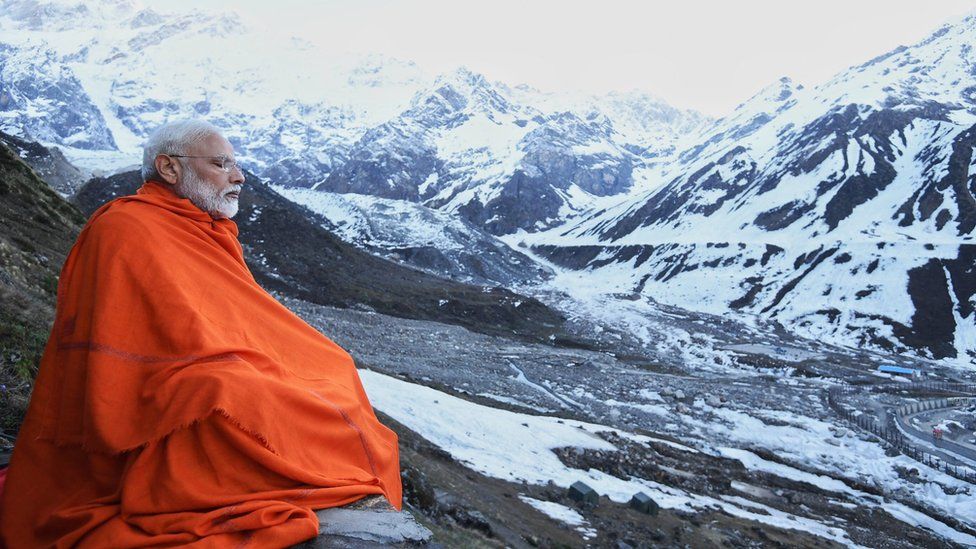

Almost all of his public interactions come across as carefully choreographed. Over the past decade, he has been photographed inaugurating countless projects, meeting supporters, snorkelling, and even meditating in a cave after the 2019 election campaign.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

Never one to miss an opportunity to connect with people directly, Mr Modi reached out to younger Indians recently, spending time with top gamers on camera and presenting awards to popular influencers.

At a recent rally in Kerala state he drew cheers when he spoke briefly in Malayalam, the local language.

“In a lot of things that Mr Modi does and which the media projects, there is a lot of symbolism involved. Where he spends every vacation, where he spends every festival – it’s with the armed forces at the border or in remote locations or with underprivileged people,” says political analyst Sandeep Shastri.

Foreign visits, including routine ones, are amplified by domestic media and celebrated at home. He addresses huge diaspora-led rallies abroad, images of which are repeatedly played on domestic TV as evidence of his global popularity. But the visits are rarely analysed by India’s mainstream media in terms of outcomes.

Divisive politics

Back in Varanasi, not everyone is so impressed. Little has changed in Lohta, a Muslim-dominated neighbourhood, where we saw overflowing drains and crumbling infrastructure.

Nawab Khan, who lives in Lohta, says weavers like him have become poorer in the past 10 years.

“The only way to prosper is to be a BJP supporter, or else you are left to struggle. Those who buy sarees have become richer, and those [predominantly Muslims] who make them have become poorer,” he alleges.

The BJP’s Dileep Patel, who is in charge of 12 parliamentary seats including Varanasi, dismisses persistent allegations about Muslims being sidelined, or the government discriminating against them, and says welfare schemes are distributed fairly.

He blames opposition parties for “frightening our Muslim brothers and sisters” before Mr Modi came to power in 2014.

“But since then, they don’t feel scared and their trust in the BJP is rising day by day,” he claims, mentioning the criminalisation of triple talaq, or the practice of “instant divorce”, as a move particularly appreciated by Muslim women.

Yet, in the past 10 years, there have been numerous attacks on Muslims by right-wing groups, many of them deadly, and anti-Muslim hate speech has soared.

“When India and Pakistan were partitioned, our ancestors rejected Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s [founder of Pakistan] call and stayed in this country. We have also given our blood to build this country. Yet we are treated as second-class citizens,” says Athar Jamal Lari, who is contesting against Mr Modi in Varanasi.

And in recent weeks, some of that feeling has appeared to bubble to the surface as the BJP’s campaign has shifted from the government’s track record to shrill rhetoric against Muslims.. Mr Modi himself has been accused of using divisive, Islamophobic language, especially at election rallies, although he denies this.

But the communal pitch suggests the BJP may be less confident than it was a few weeks ago.

Political analyst Neelanjan Sircar says the party may be trying to shore up its supporters in states like Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, where Hindu-Muslim polarisation has paid off in the past. This is especially important for revving up its young mobilisers, who might also be affected by issues such as unemployment.

The party also seems nervous about there not being an overwhelming national issue – or wave – like in the past two elections. In 2014, there was massive public anger against a Congress-led government seen as corrupt, and in 2019, national security dominated the campaign after a deadly attack on Indian troops was followed by air strikes against alleged militant targets in Pakistani territory.

“So it may still very much be a vote about how much you trust the leader, or how much you trust the party, but in the absence of a wave, the issues become much, much more local,” Mr Sircar says.

The BJP hopes Mr Modi’s larger-than-life image will get them over the line, but analysts say it could be a problem as well.

‘Aura of leadership is central’

“Who stands for the election [for the BJP] is not as important because the aura of the prime minister is so central to the emotive connect on the basis of which the political drama and the cycle of elections is unfolding,” says public policy analyst Yamini Aiyar.

Some analysts warn, however, that overly centralised decision-making which does not privilege local leaders could be detrimental for the BJP in the long term.

Mr Patel, however, credits Mr Modi – a “self-made leader” – with transforming the BJP.

“Earlier, the opposition would allege that the BJP was an organisation dominated by rich, urban, upper-caste people. Their allegations were baseless, of course. But Mr Modi’s efforts have established that the BJP is a party of rural people, the poor, farmers, tribal people, workers, women and those from marginalised communities,” he says.

In Kakrahiya, one of Mr Modi’s adopted villages in his constituency, we met local BJP leader Manoj Singh who said the PM was well-informed about his constituency.

He remembers Mr Modi inquiring about the death of a local BJP volunteer.

“I got a call at 9.30pm from the prime minister asking what had happened. He is always concerned about even small things that happen here.”

Uneven growth

It’s not just residents in Lohta, the Muslim-dominated neighbourhood in Varanasi, who feel they are getting a raw deal – people in other pockets of the prime minister’s constituency are still waiting to see signs of change but many more have benefitted from improvements in things like sanitation, roads and other infrastructure.

In Chetavani village, just a few miles away from Kakrahiya, we met dozens of people living in dusty shanties.

“We were evicted from our old homes by local officials and brought here. We can’t even get water properly here,” says Rajinder, 26. But he says he will still vote for Mr Modi.

Like Shiv Johri Patel the saree weaver, many people here were angry at local officials – but not at the prime minister.

At a glance, Kakrahiya is very different – it has an air of relative prosperity, and there is running water for its residents.

“We now have toilets, gas cylinders and houses,” Chiraunji says, sitting in the kitchen of her half-built home. She says she admires Mr Modi.

She gets a free cooking gas cylinder under a government scheme, but can’t refill it frequently.

Analysts say handouts cannot make up for sustained investment in health, education and other infrastructure. Another of Mr Modi’s biggest challenges is generating quality jobs for India’s burgeoning young, restless population.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

India’s economy has surged with growth rates exceeding 7% – it’s currently fifth-largest globally, ahead of the UK. The fruits of this impressive growth haven’t reached millions of poor people, but it’s hard to say if anger against this is widespread enough to defeat Mr Modi.

“People may not be judging incumbency or anti-incumbency on how well you do on things like inflation or economic growth or joblessness,” says Mr Sircar.

Instead, he says, Mr Modi’s playbook is a scaled-up version of a long-standing model of politics where parties are often the “vehicle for a single individual or family”.

“The purpose of that model is to build a direct connection between the leader and the voter,” he says.

A divided opposition

Mr Modi has been helped by the absence of a strong, coherent opposition to challenge him nationally – when he’s looked vulnerable they have failed to capitalise.

The prime minister was the face of the 2016 demonetisation drive – scrapping high-value currency notes in a bid to crack down on illegal money – which many economists say had disastrous consequences. His government was also criticised for its handling of Covid.

Opposition parties accuse him of crony capitalism, saying he favours some big business families. He’s also been criticised for not visiting Manipur state since ethnic conflict erupted there last year.

Yet, his opponents have largely failed to land their punches – and these controversies don’t seem to matter to his many admirers.

“A large part of the image management of Mr Modi is about making sure that he’s never associated with a negative outcome that can be pinned on somebody else or some other factors,” says Mr Sircar.

Supporters praise the PM for “never taking a break”. His relentless programmes and constant media coverage consolidate the impression that he is always working.

And that’s reflected in coverage – a large section of the media and pro-BJP social media channels also often portray opposition leaders as reluctant to work hard.

Mr Shastri says when Mr Modi came to power in 2014, the previous government was seen as “ineffective”.

“In contrast you have Mr Modi, who makes it look as if he is 24×7 in charge, 24×7 available, 24×7 amidst the people with no family of his own, no commitments to anything personal, all your time devoted for the state,” he says.

However, Mr Sircar points out that a big challenge the BJP faces is “extreme spatial concentration”.

“They have continually had one problem – they have relied extremely heavily on sweeping a small number of states [mostly in northern India],” he says.

Mr Modi has been working hard to make inroads in the south – in the run-up to voting in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, he visited both states a number of times, holding huge rallies. Whether this pays off on results day remains to be seen.

And in the past two weeks, the opposition has appeared more united and coherent in its messaging.

Ms Aiyar says there is a lot to criticise in India’s opposition but points out they are right in complaining there is no level playing field.

“The way in which the media has been captured, the using of law to curb the space for dissent, the absence of data – all of that collectively creates conditions where it is extremely difficult for an alternative narrative to even generate,” she says.

Additional reporting by Anshul Verma and Zubair Ahmed

All photos copyright