In 2019, Pann Pann started her first job – maintaining medical records – at a government-run hospital in Myanmar’s southern Bago city. She aspired to be the hospital’s chief records officer.

But four years on, the 25-year-old is waiting tables in Bangkok, her dreams pushed to the back burner as a brutal military regime continues to rule her country.

“If not for the coup, I would never have left,” she says. “I wanted to build my life in Myanmar. But there is no safe place in my country anymore.”

When Pann Pann finished college, Myanmar was still enjoying a rare bout of political freedom, the first in 50 years. The economy, racked by decades of instability, started to recover as tourists arrived and foreign investment poured in.

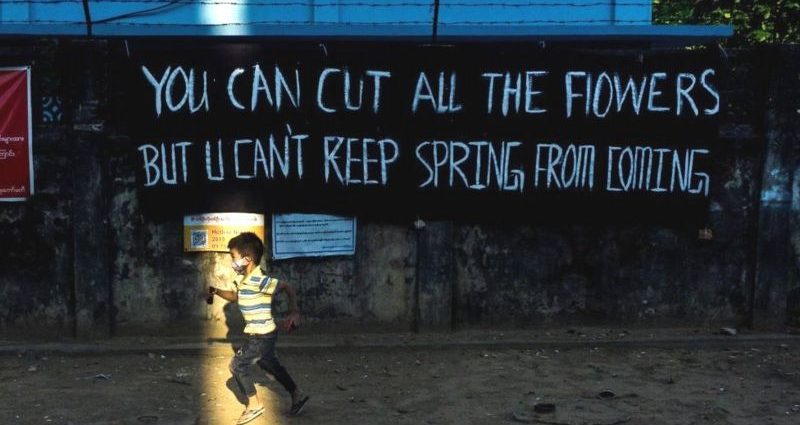

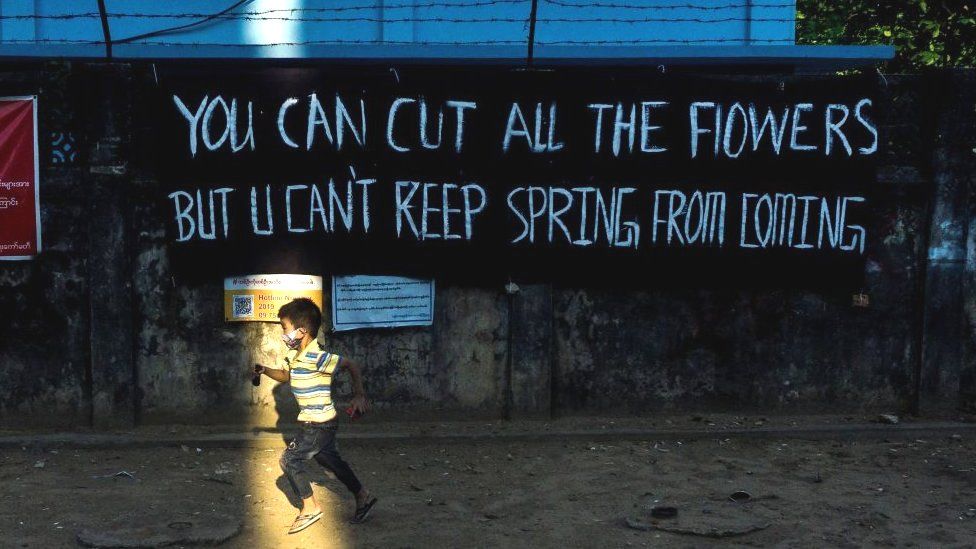

Then came February 2021. The army arrested Aung San Suu Kyi, a democratically elected leader, sparking huge anti-coup protests that set off a bloody civil war and sent the economy into a tailspin.

The early days of the post-coup movement were marked by a youthful resistance, but that optimism soon dwindled. The risks of staying in Myanmar increased for those like Pann Pann, who had been an active member of the civil disobedience movement, a vast strike spearheaded by public sector workers, against military rule.

The UN estimates some 70,000 people have left the country since the coup. The exodus has been driven by disheartened young people looking for jobs to support their families. According to the International Labour Organisation, 1.1 million fewer Burmese were working in the first half of 2022, compared to the same period in 2020.

For decades, the country’s ethnic minorities had fled persecution. Then hundreds of thousands of Rohingya joined them as the army was accused of committing genocide against the Muslim community. Now, in the wake of the coup, dissidents, activists and even ordinary Burmese, weary of the civil war, wanted out.

For Pann Pann, the decision to leave Myanmar was not an easy one.

She had spent months evading authorities by moving from one relative’s house to another. She continued to live in Bago as several of her friends were killed by the junta. Finally, a friend in the US helped raise money for her one-way air ticket to Chiang Mai.

When she didn’t find a job there, she moved to Bangkok. She cycled through seven under-the-table jobs – as a babysitter, housekeeper, waitress and construction worker – within the first year. Pann Pann still doesn’t have a work permit.

But she says there is some semblance of stability. She now earns 12,000 baht (£280; $350) a month, enough to foot rent for a small room close by.

“Life in Thailand is difficult because I cannot speak their language, and cannot speak good English. I still can’t stay here legally… but it is safer,” she said.

She believes her name is on a “black list” which makes her nervous about going home. So she doesn’t know when she will see her family again.

“But I think this is the right decision,” she says. “I did not come to Thailand because it is more comfortable. I didn’t even know what Thailand was like. But when I was in Myanmar, I only had one thing on my mind: I have to leave.”

Fear is also what forced Augustine Thang to bike across the border from Myanmar’s Chin state to Mizoram in India in January last year, with his wife and two young children.

He never went back, although he is still praying for an opportunity to.

The 34-year-old was a deputy manager at the Chin state’s department of social welfare when the coup happened. He joined the civil disobedience movement a week later.

Fear of reprisals from the army and the pressure of having to provide for his family proved too much.

“It was a difficult decision. I love my country, my village, and I want to work for my people, but I chose to leave because our lives are valuable,” he said.

Thang now takes on ad-hoc jobs in construction.

“I wanted to become director of my [former] department and to focus on child and youth development. Now I do not have regular work. I help friends and they share their earnings with me. This is not satisfying,” he said.

“[Mizoram] is not our home, but I don’t have a choice.”

Among the things Thang misses most about Myanmar is “being able to live peacefully, to fish at sea, and have fresh fish”. But he remains hopeful that his country will “regain democracy” one day with the support of international organisations like the UN.

Not everyone who left Myanmar fled out of fear. Some like Julia Khine, a Burmese engineering student in Hong Kong, left to study. But watching what has happened to her country has also made her more reluctant to return.

“I hope to contribute to my country and people, but from outside Myanmar,” says the 21-year-old who was last home in August 2022. After graduating, she says, she wants to travel across the world “to speak about the injustice that is happening in Myanmar”.

She says it has been disconcerting to live a relatively peaceful life when friends and family back home are confronted with violence and instability every day.

“It’s been hard to make close friends in Hong Kong because they cannot relate to my concerns,” she says. “I was horrified by the recent air strikes [in Myanmar], but I didn’t feel they would understand my feelings, so I just had to pretend nothing was going on.”

The air strike she is referring to killed more than 100 people in a village in the north-west.

She is also reluctant to share details about her life with people back home – and even stays off social media – for fear of seeming insensitive.

Parents of her friends who were killed by the army would be particularly “triggered if they see that I’m doing good”, she added.

Meanwhile Pann Pann sorely misses her family and friends from church. But she keeps telling herself that she is already the fortunate one.

“Many of my friends are still in hiding, moving from house to house. Some have been killed,” she says. “I always remind myself that their lives are more difficult than mine, so I must be strong.”

Related Topics

-

-

1 February 2022

-