“I’m sure I will kill you – if I get to fire first,” warns the father.

He’s on the phone to his son, who is serving in the Myanmar military.

Bo Kyar Yine joined the armed resistance after a military coup ousted Myanmar’s democratically elected government in February 2021 – the brutal civil war that followed has split his family. He is now fighting against a military junta his son defends.

“You may give me a chance as your father, but I will not spare you,” he tells his son, Nyi Nyi, as he sits under a banyan tree in the forest. “We are worried for you.”

“Yes, I’m worried about you too, father,” comes the reply. “You encouraged me to become a soldier.”

Bo Kyar Yine has two sons in the armed forces. The elder no longer answers his calls.

“The army destroys homes, sets them on fire,” Bo Kyar Yine says, imploring his son to leave the military. “It kills people, shoots to kill protesters unjustly, kills children without reason, rapes women. You may not know that.”

“That is your view, father. We don’t see it that way,” Nyi Nyi replies respectfully. Despite such denials, atrocities by the military are widespread and well-documented.

After the call, Bo Kyar Yine says he’s trying to convince both his sons to defect to the resistance. “They are not listening so it will be up to fate if we meet in a battle”.

“In a handful of beans, there are two or three hard ones. It’s the same in a family,” he says. “It’s possible that some are not good.”

Bo Kyar Yine and his wife Yin Yin Myint had eight children – when two of their sons enlisted, they were proud. The father kept photos of their military graduation ceremony as mementos. Both sons became officers.

It was a great honour to have soldiers for sons, he says. This was a time when people in this part of central Myanmar welcomed the army into their villages with flowers.

Yin Yin Myint says the whole family worked in the fields to earn money so the two boys could be educated and go on to join the military.

Before the civil war, a job in the Tatmadaw, as Myanmar’s armed forces are known, would bring higher social and economic status for the family.

But last year’s coup changed everything.

When Bo Kyar Yine watched the military ruthlessly crack down on unarmed pro-democracy protesters he could no longer support them and urged his sons to leave the army.

“Why did they shoot and kill the people demonstrating? Why did they torture them? Why are they killing people without reason?” he asks, as he chews betel nut in his base in the forest.

He says he is heartbroken by it all.

Before the military coup, Bo Kyar Yine was a farmer who had never held a gun. Now, he’s the leader of a civilian militia unit.

They’re part of a loose network called the People’s Defence Forces (PDF), who are fighting to restore democracy against the much bigger and better-armed military.

He refers to soldiers now as “dogs”, an extremely derogatory term in Myanmar.

“When a dog column comes in [to a village], they rape women, they burn down homes and loot properties… We have to stand against them,” he says.

Bo Kyar Yine leads a unit of about 70 pro-democracy fighters who call themselves the Wild Tigers. They have only three automatic rifles.

Four of his other sons are fighting alongside him. The two sons in the military are stationed just 50km (30 miles) away from their rebel base.

“We thought we could rely on our soldier sons,” says Yin Yin Myint sadly. “But now they are troubling us.”

‘The gunfire sounded like it was raining’

It was 3am one morning in late February when Bo Kyar Yine’s PDF unit received a phone call from a nearby village. The army was raiding them.

“We need help, dogs [soldiers] have entered our village, come and help us. Send us reinforcements,” was the message.

Min Aung, the second eldest son, was the first to get ready to leave. His mother, knowing that she could not stop him, prayed for his safe return.

The Wild Tigers left in a convoy of motorbikes. Bo Kyar Yine rode at the front with Min Aung, leading the unit as usual.

They were travelling along a familiar route that had been safe in the past when they were ambushed.

“There was nowhere to take cover, no big trees or anything,” says Min Naing, another son.

“They shot at us like popcorn popping,” he says. “We were in the killing field. Our weapons didn’t match theirs.”

Bo Kyar Yine ordered them to retreat. They took cover behind a rice paddy dyke.

“Someone among them seemed to know me,” says Bo Kyar Yine.

He feels he was the focus of their attack.

“I shot at them as I started to run and then just kept firing and ran.”

Yin Yin Myint was waiting anxiously at the camp and could hear what was happening.

“The gunfire was so constant it sounded like it was raining,” she says through tears.

Within hours of the ambush, the military posted graphic photos of the dead on Facebook, boasting they had killed 15 people.

It was then that Yin Yin Myint realised she had lost Min Aung, the child she was closest to.

“My son cared deeply for me,” she says. “He would clean the kitchen for me. He washed my clothes. He collected my sarongs from the washing line. He was really good to me.”

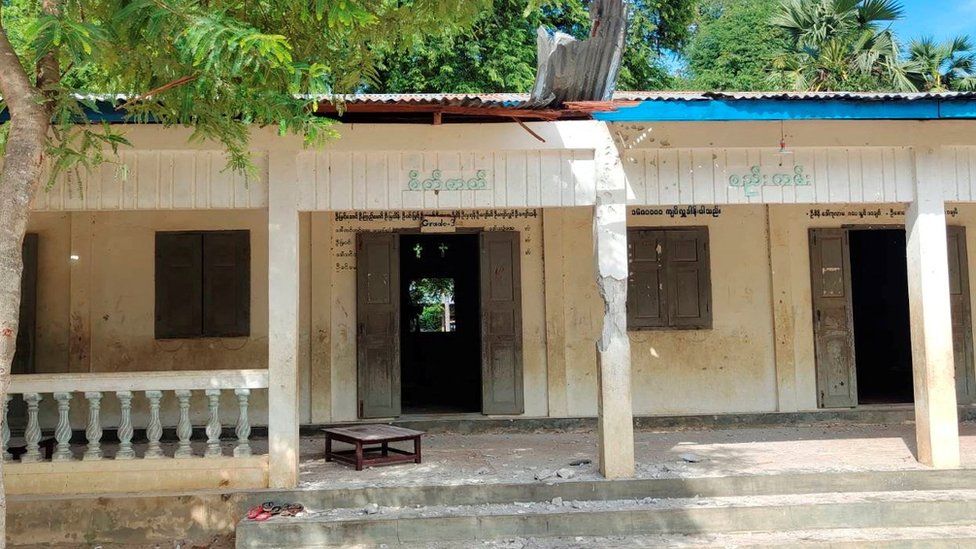

In June, soldiers burned the family’s home and all their possessions to the ground along with 150 houses in their village. There have been arson attacks by soldiers all over the country, especially in central Myanmar.

It seems certain the military knew of Bo Kyar Yine’s role in the resistance – whether they are aware he has sons in the armed forces is not clear.

Yin Yin Myint is struggling to cope with all she has lost.

“My home was burnt down and I lost my son. I can’t take it all really. My mind is not exactly with my body, it’s like I am crazy,” she says.

Since the military seized power, more than 1.1 million people across Myanmar have been displaced and at least 30,000 homes burnt down.

More than 2,500 people have been confirmed killed by security forces since the coup, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners says. Total casualty figures on both sides are estimated to be 10 times higher, according to data from conflict monitoring group Acled. The military has admitted battlefield losses, but provided no details.

The family tried for two days to retrieve Min Aung’s body but it was impossible because soldiers kept guard over the area.

“I couldn’t even pick up his bones,” says his mother. “I’m angry about that. I want to go and fight but they won’t take me because I’m a woman over 50.”

‘I won’t spare you or anybody’

Bo Kyar Yine believes the popular uprising will win and he will rebuild the family home.

But as the civil war intensifies, this seems a long way off.

As his two middle sons refuse to leave the military the family remains split, reflecting the nation’s divisions.

“We are not fighting the military because we want to,” Bo Kyar Yine tells his soldier son.

“It is because your dog leaders are unfair so we have to fight. Because of you guys your brother was taken.”

Nyi Nyi replies that he knows his brother is dead.

“Come and look at your own village. It’s all ashes now,” his father tells him angrily.

“We couldn’t even save your pictures. How my heart aches.”

Bo Kyar Yine then warns his son.

“If you come to my area and start a battle, I won’t spare you or anybody. I will only stand with the people – I can’t stand with you,” he says, before hanging up.

*All names in this report and details of locations have been withheld to protect people’s identity.

-

-

20 September

-