Getty Images

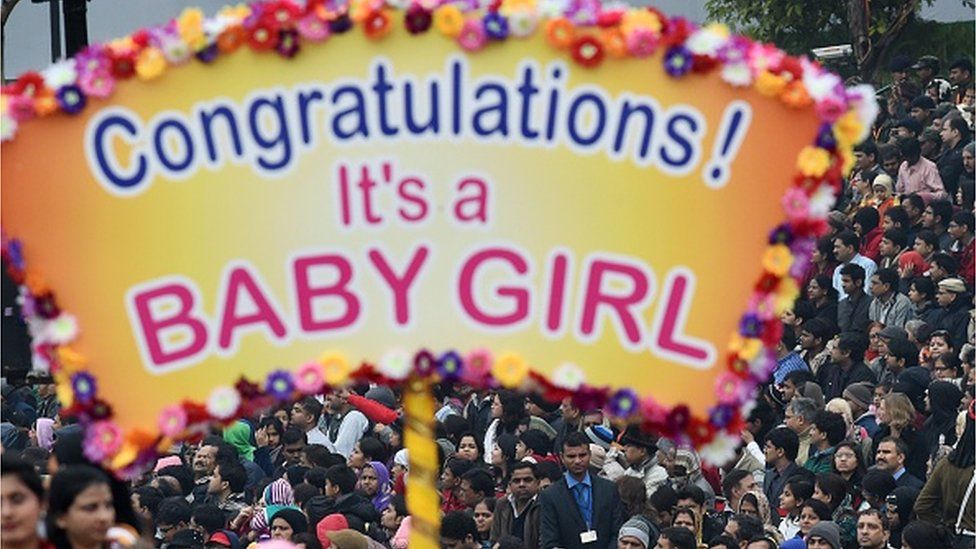

Getty Images Is certainly India’s skewed sex ratio at delivery – meaning more boys are delivered than girls : beginning to normalise?

Yes — and it’s fuelled largely by changes within the Sikh community, based on a study by US-based Pew Research Center.

The non-profit think tank studied the data from the latest National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) – the most comprehensive household survey of health and interpersonal indicators by the Indian native government, conducted in between 2019-2021 – having a special focus on just how gender imbalance at birth has been transforming within India’s major religious groups.

The study says sex percentage at birth (SRB) has been improving designed for Hindus, Muslims plus Christians, but the greatest change seems to be amongst Sikhs – the girls that previously had the greatest gender discrepancy.

Experts, however , recommend caution while interpreting this data since the survey covers just about 630, 000 of India’s 300 million households.

“The true picture will be known only after the census which matters the entire population and provides a more accurate accounts, ” says researcher and activist Sabu George.

India’s well-documented preference for kids has historically resulted in a very skewed sexual intercourse ratio in favour of men.

It’s rooted in widely-held cultural beliefs that a male child would carry the household name, look after the fogeys in their old age, and perform the traditions on their death : while daughters would certainly cost them dowries and leave all of them for their matrimonial homes.

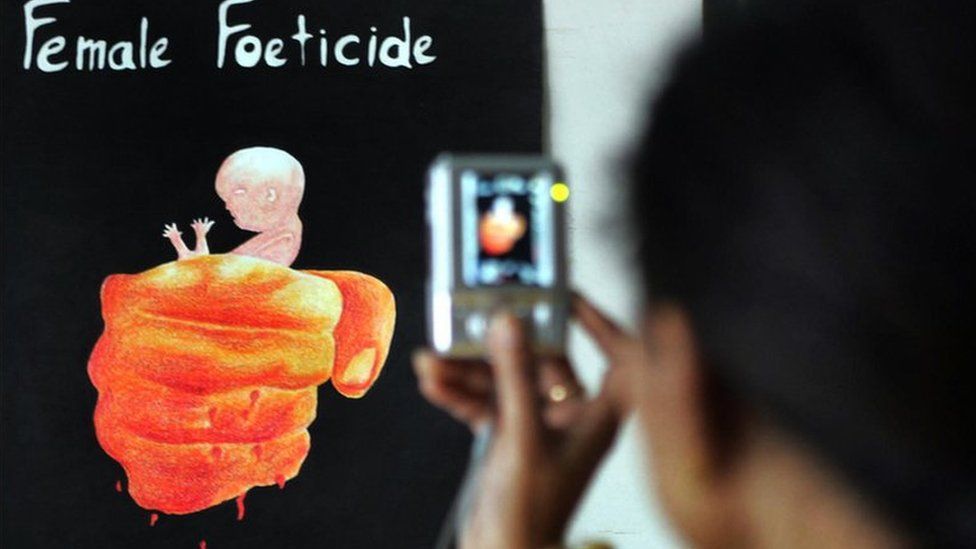

This anti-girl prejudice, coupled with the easy availability of pre-natal sex testing from the 1970s, provides seen tens of a lot of female foetuses aborted – a process referred to as female foeticide.

Regardless of a government ban on sex-selection lab tests in 1994, campaigners say it continues to be rampant. Nobel laureate Amartya Sen provides described India because “a country of missing women” and the UN estimates that will nearly 400, 000 female births : or 3% of female births : are missed annually as a result of gender biased sex selection.

Getty Pictures

Experts say if there’s no intercourse selection, for every 100 girls born, there will naturally be 105 male births, however the number of female births in India has been much lower for decades now.

According to the 2011 Census, India had about 111 boys for each 100 girls. The amount improved slightly in order to about 109 in the NFHS-4 (in 2015-16) and is at 108 now.

This new data, Pew says, suggests that the particular preference for sons has been waning and Indian families have become less likely to use intercourse selection to ensure birth of sons rather than daughters.

The biggest change, this says, is seen one of the Sikhs – a community that makes up less than 2% of the Native indian population, but has accounted for an estimated 5% – or around 440, 000 : of the nine million baby girls that went “missing” in India between 2k and 2019.

The wealthiest of India’s major religious organizations, Sikhs were the first in India to use sex determination exams widely to discontinue female foetuses.

The community saw its sex ratio at birth peak at 130 in the early 2000s – it is now down to 110 which is a lot closer to the nationwide average of 108.

“This follows years of government efforts to curb sex choice – including analysis on pre-natal intercourse tests and an enormous advertising campaign urging moms and dads to ‘save the woman child’ – plus coincides with wider social changes like rising education plus wealth, ” the study says.

Researcher and activist Sabu George questions the assertion that India’s sex ratio at birth has begun to normalise.

“The one-point decrease from NFHS-4 in order to NFHS-5 is only a slight improvement. To call it normalisation is an exaggeration, a distortion, inch he says.

Mr George also points out that this NFHS-5 data had been gathered at a time whenever India was striving to cope with an outbreak.

“Covid murdered four million people, the health system experienced collapsed and a lot of additional health services, which includes birthing services, had been impacted across the country, inch he says, adding that the data collection at that time, especially in some of India’s bigger, more populous states, was faraway from robust.

Getty Images

He does concur that female foeticide has been declining within Punjab and Haryana – where a most of Sikhs live – over the years.

Amit Kumar, a gender specialist based in Punjab, states despite the decline, this individual finds little modify in the attitudes on the floor.

“I do not find any difference within narratives today through what I found in books from a 100 years back again. Agents of patriarchal structure also develop with the time, so you see that the same methods exist, the same attitudes exist, but they obtain modified and look a bit different on the ground. That it is old wine in a new bottle, ” he says.

The PhD student in masculinity studies, which undertook a survey two years back in countryside Punjab, says 2 yrs back, he met a 28-year-old villager who said that he’d have killed his daughter if his wife had given birth to a female.

“In Punjab, a girl is seen as a burden, a legal responsibility, and it’s very normal and culturally approved for people to seek blessings at Gurdwaras (Sikh temples) and shrines for a male kid. ”

If you request people a direct question, he says, they will usually deny that they discriminate between boys and girls. In case you probe deeper, you find the boy preference very much is present, with most people saying having one son is necessary because he has to perform rituals after their death.

During the past few years, Mr Kumar says, hoardings and advertisements have come upward that warn people against resorting to illegal sex dedication tests and that has created some fear one of the public.

“So sex determination tests and abortions have decreased a bit, but merely a bit and everyone knows which clinic in order to consult if they wish to abort a female foetus. ”

What is furthermore worrying, he says, is that if you look at the public crime data, it shows a consistent embrace the numbers of “miscarriages and abandonment of the girl child” from 2012 – which could mean that girls are being neglected after delivery.

“Only behavioural change can stop the neglect of the girl child, but that’s a long lasting process, ” Mister Kumar says. “It takes time to change attitudes. And the pace of change is very slow. ”

-

-

18 Nov 2021

-

-

-

six March 2017

-