Getty Images

Getty ImagesEarly on Friday night, a 31-year-old women apprentice physician retired to sleep in a lecture hall after a gruelling time at one of India’s oldest hospitals.

It was the final moment she had been spotted intact.

The next day, her colleagues discovered her half-naked figure on the floor, bearing considerable injuries. A medical charity employee was eventually detained by police in connection with what they claim is a situation of murder and murder at Kolkata’s 138-year-old RG Kar Medical College.

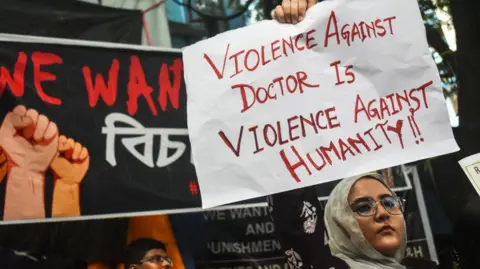

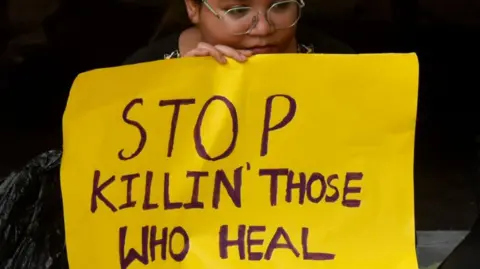

Enraged specialists went on strike in both the area and throughout India, calling for stringent federal laws to protect healthcare workers. The tragic occurrence has once more highlighted the murder against healthcare workers in the nation.

Women make up nearly 30% of India’s doctors and 80% of the nursing staff. They are also more vulnerable than their male colleagues. Official data reveals a troubling 4% increase in crimes against women in 2022, with over 20% of these incidents involving rape and assault.

Last week’s incident at the Kolkata medical exposed the alarming safety concerns that many of India’s state-run health facilities face.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt RG Kar Hospital, which sees over 3, 500 patients everyday, the overworked apprentice doctors- some working up to 36 hours right- had no designated sleep rooms, forcing them to find rest in a third-floor seminar room.

According to reports, the arrested suspect was a person volunteer with a troubled previous who had unlimited access to the hospital and was reportedly captured on surveillance. According to the police, no background checks on the charity were done.

” We just go home to rest because the doctor has always been our first home.” We always imagined it could be this risky. Then, after this tragedy, we’re terrified”, says Madhuparna Nandi, a young doctor at Kolkata’s 76-year-old National Medical College.

Dr. Nandi’s personal experience demonstrates how women doctors in India’s authorities hospitals have accepted working in unsafe conditions.

At her hospital, where she is a native in gynaecology and midwifery, there are no designated rest areas and separate toilets for female specialists.

If the staff allows me to use the restrooms for the individuals or the nurses, I do so. I occasionally sleep in a cramped waiting room or an empty individual bed when I work later, according to Dr. Nandi.

After working for 24-hour shifts that begin with ambulatory duty and proceed through hospital rounds and postpartum rooms, she claims to feel uncomfortable even in the space where she sleeps.

One day in 2021, during the top of the Covid crisis, some gentlemen barged into her chamber and woke her by touching her, demanding,” Get up, get away. See our client”.

” I was totally shaken by the incident. However, Dr. Nandi says that we never anticipated that a doctor may be raped and murdered in a hospital.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat happened on Friday was not an isolated incident. The most shocking case remains that of Aruna Shanbaug, a nurse at a prominent Mumbai hospital, who was left in a persistent vegetative state after being raped and strangled by a ward attendant in 1973. She died in 2015, after 42 years of severe brain damage and paralysis. More recently, in Kerala, Vandana Das, a 23-year-old medical intern, was fatally stabbed with surgical scissors by a drunken patient last year.

After a death or over requests for immediate medical attention, doctors in crowded government hospitals frequently face unlimited access and face unlimited medical treatment. Kamna Kakkar, an anaesthetist, remembers a harrowing incident during a night shift in an intensive care unit ( ICU) during the pandemic in 2021 at her hospital in Haryana in northern India.

” I was the lone physician in the ICU when three gentlemen, flaunting a president’s name, forced their way in, demanding a little in-demand controlled substance. Knowing that the security of my clients was in danger, Dr. Kakkar told me,” I gave in to defend myself.”

Namrata Mitra, a physician from Kolkata who studied at the RG Kar Medical College, claims that her doctor father had frequently take her to function because she felt uneasy.

Getty Images

Getty Images” During my on-call work, I took my papa with me. Everyone laughed, but I had to sleep in a room with a locked metal wall that only the nurse was unlock if a person arrived, Dr. Mitra wrote in a Twitter publish over the weekend.

” I’m not ashamed to admit I was scared. What if someone from the clinic- an assistant, or even a individual- tried everything? Not everyone has the same pleasure as my father, but I benefited from it because he was a doctor.

Dr. Mitra spent her evenings in a deteriorating one-story tower that served as the vet’s dormitory while working in a region in West Bengal.

” From twilight, a group of guys do gather around the house, making lewd remarks as we went in and out for situations. They had allegedly beg us to test their blood pressure in order to make an appearance, and they would even peer through the cracked bath windows, she wrote.

Years later, during an emergency move at a federal hospital,” a group of drunken men passed by me, creating a ruckus, and one of them actually groped me”, Dr Mitra said. When I attempted to complain, I discovered the police officers dozing off with their firearms in hand.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThings have worsened over the years, says Saraswati Datta Bodhak, a pharmacologist at a government hospital in West Bengal’s Bankura district. Both of my daughters are young doctors, and they tell me that the state’s hospital campuses are overrun by anti-social groups, drunks, and touts, she says. Dr. Bodhak recalls that while visiting a top government hospital in Kolkata, a man with a gun was spotted wandering about.

India lacks a stringent federal law to protect healthcare workers. Although 25 states have some laws to prevent violence against them, convictions are “almost non-existent”, RV Asokan, president of the Indian Medical Association (IMA), an organisation of doctors, told me. A 2015 survey by IMA found that 75% of doctors in India have faced some form of violence at work. “Security in hospitals is almost absent,” he says. “One reason is that nobody thinks of hospitals as conflict zones.”

Some states like Haryana have deployed private bouncers to strengthen security at government hospitals. In 2022, the federal government asked the states to deploy trained security forces for sensitive hospitals, install CCTV cameras, set up quick reaction teams, restrict entry to “undesirable individuals” and file complaints against offenders. Nothing much has happened, clearly.

Even the protesting doctors do n’t seem to be very hopeful. ” Nothing will change… According to Dr. Mitra,” the expectation is that doctors should work round-the-clock and endure abuse as a norm.” It is a disheartening thought.