A Muslim son returned red-faced from a well-known university in the north Indian city of Agra six years ago.

” My colleagues called me a Muslim terrorist”, the nine- season- old told his mother.

Reema Ahmad, an artist and counsellor, remembers the time brilliantly.

” Here was a young, outspoken boy, and his palm had nail marks on his left. His fists were clenched so strongly. He was therefore irritated”.

When the professor stepped out, her son’s classmates were having a mock struggle, she said.

” That’s when one group of boys pointed at him and said,’ This is a Pakistani terrorist. Remove him!'”

Ms. Ahmad later ordered her son to leave the classroom. Nowadays, the 16- year- ancient is house- schooled.

” I sensed the society’s tremors through my brother’s experiences, a sensation I not recall having in my own children growing up around”, she says.

” We might have avoided feeling Muslim all the time because of our school pleasure.” Today, it seems like category and privilege make you appear more likable.

Ever since Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party ( BJP) swept to power in 2014, India’s 200 million- strange Muslims have had a turbulent trip.

” Muslims have become next- group citizens, an unknown majority in their own state”, says Ziya Us Salam, writer of a fresh book, Being Muslim in Hindu India.

However, the BJP and Mr. Modi dispute the allegations that minority in India are being treated unfairly.

Despite the city’s undulating lanes and crowded homes, Ms. Ahmad feels a change. Her family has lived in Agra for years, counting some Hindu friends.

The information on the team read,” If they hit us with weapons, we will enter their houses and kill them,” in line with Mr. Modi’s earlier statement about putting Indian enemies and terrorists at risk in their homes.

” I lost my cool. I told my friends what’s wrong with you? Do you approve of killing children and residents? Ms Ahmad recalled. She backed the idea of harmony.

The effect was sharp.

” Somebody asked, are you pro- Bangladeshi simply because you are Muslim? They accused me of being anti- national”, she said.

” Immediately, being anti-national was equivalent to being anti-national,” the statement read. I told them that I was n’t required to be aggressive in order to assist my country. I quit the group”.

Other techniques can be felt as well by the changing environment. For lengthy, her large apartment has been a lounge for her brother’s classmates, regardless of gender or religion. However, Hindu women are now required to leave by a specific time and not remain in his room as a result of the “love jihad” monster.

” My dad and I sat my child down and told them that the environment is not great- you have to control your friends, remain vigilant, not stay up too soon. You not know. Things may change into’ like terrorism’ at any time”.

Fifth-generation Agra citizen Erum has noticed a change in conversations with children while working in nearby schools.

” Do n’t talk to me, my mother has told me not to”, she heard one child tell a Muslim classmate.

” I am thinking, definitely?! This reflects the deeply ingrained phobia]of Muslims ]. This will develop into a condition that we ca n’t easily treat,” said Ms. Erum.

But for herself, she had plenty of Hindu companions, and did not feel uncomfortable as a Muslim person.

It’s just not about the kids. In his little company along a bustling Agra city, Siraj Qureshi, a local columnist and religious organiser, laments the tearing of the ancient bonhomie between Hindus and Muslims.

He relates a recent incident in which a man who delivered mutton in a city was stopped by Hindu right-wing group members, handed over to the police, and later imprisoned. ” He had the proper licence, but the police still arrested him. He was later released”, Mr Qureshi says.

Many in the community notice a change in how Muslims travel by train, which was reportedly brought on by incidents where Muslim passengers were reportedly attacked for allegedly carrying beef. ” Now, we’re all cautious, avoiding non- vegetarian food in public transport or opting out]of public transport ] altogether if we can afford to”, says Ms Ahmad.

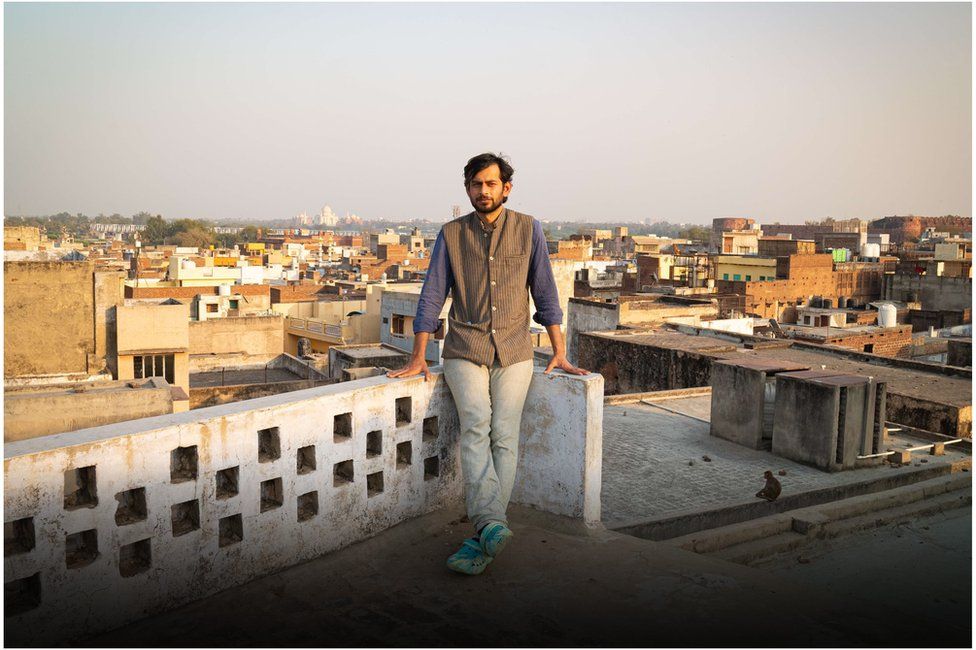

Kaleem Ahmed Qureshi, a software engineer- turned jewellery designer and musician, is a seventh- generation Agra resident, who also leads heritage walks in the city.

Carrying his rubab, a lute- like musical instrument commonly played in Afghanistan, he took a shared taxi with a Hindu co- passenger from Delhi to Agra recently. ” When he saw the case, he asked me to open it, fearing it was a gun. I sensed that his response was influenced by my name, Mr. Qureshi claims.

” There is this anxiety]which we live with]. When I travel now, I have to be very aware of where I am, what I say, what I do. Even though I tell the train ticket checker my name, I still feel uneasy.

Mr. Qureshi sees a clear cause:” Politics has mixed poison in the relationships between the communities.”

On a recent warm afternoon in Delhi, Syed Zafar Islam, the BJP’s national spokesperson, said there is no reason for Muslims to be anxious, blaming “irresponsible media houses” for the rise in Islamophobia.

” Sometimes, a small incident occurs, and the media amplifies it like it has never happened before. In a country of 1.4 billion people, several such incidents can take place between communities or within communities”, he adds.

” You cannot generalise one or two incidents ]and say the ruling party is anti- Muslim]. If someone portrays it as something targeted against Muslims, they are wrong”.

I asked him how he’d react if his children came home from school, saying classmates had labelled him a” Pakistani terrorist” for the family’s religion. The ex- banker, who joined the party in 2014, has two children, one currently in school.

” Like any other parent, I would feel bad. The school is in charge of making sure such things do n’t occur. Parents should make sure they do n’t say such things”, he said.

” People know this is rhetoric. Has our government or political party made such statements? Why do people who say such things get so much space in the media? We feel upset when media gives space to such people”, Mr Alam said.

But then, what about the lack of Muslim representation? The BJP has no Muslim ministers, MPs in either house of the parliament, and only one member of a local assembly ( MLA ) among the more than 1, 000 nationwide.

Mr Alam, a former BJP MP himself, said this was not intentional.

The Congress and other opposition parties are using Muslims to advance their goals by defeating the BJP. Which party will give a Muslim candidate a ticket if he is fielded by a party but Muslims do n’t vote for him?

It is true only 8 % of India’s Muslims voted for the BJP in 2019, and are increasingly voting as a bloc against Mr Modi’s party. In the 2020 Bihar state elections, 77 % supported an anti- BJP alliance, in 2021, 75 % backed the regional Trinamool Congress in West Bengal, and in 2022, 79 % supported the opposition Samajwadi Party in Uttar Pradesh.

However, Mr. Alam contends that the opposition parties under the leadership of Congress created “fear and anxiety” in the electorate to ensure their loyalty. The Modi government, on the other hand, “does n’t differentiate]between communities ]”.

” Every person gets the welfare programs.” The biggest beneficiaries of some of the schemes are Muslims. In the last ten years, there have n’t been any major riots. In fact, more than 50 people died in Delhi in 2020 as a result of rioting over a contentious citizenship law, the majority of whom were Muslims; however, India has seen far worse in the years since independence.

Mr. Alam attributed the community’s self-insultion to the general.

” Muslims must introspect. They should reject being treated as a]mere ] vote bank, and not be influenced by religious leaders.

Mr. Modi is making an effort to unite society so that people can coexist happily and not be misled.

Under Mr. Modi’s leadership, he asked how he felt about the future of Muslims in India.

” It is very good…. Minds are changing slowly. The BJP will have more Muslims joining it. Things are looking up.”

It’s difficult to say whether things are improving or not.

Many Muslims claim that their country is going through a process of reform in these troubled times.

” Muslims are looking within and getting educated. Muslim intellectuals and educationists are making a concerted effort to assist deserving, needy community students in getting educated. The effort to make improvements on your own is admirable, but it also demonstrates a lack of faith in the government, according to Mr. Salam.

Arzoo Parveen, one of the few people with education who can see a way out of poverty with her family in Bihar, India’s poorest state.

Unlike Ms Ahmad’s son, the road block was not religious tensions, but her own father, scared of what others would think.

He said the locals will talk about our money problems at home because you are a mature girl. I told him that we ca n’t continue to live this way. Women are moving ahead. We ca n’t put our futures on hold.”

Arzoo’s dream is to become a doctor, inspired after hearing how her mother died at the local hospital. But it was the stories of women becoming doctors and engineers that made her believe it was possible, according to the women’s teachers in the village.

” Why not me? She requested, and she did so with a year’s notice, becoming the first woman in her family to pursue higher education.

Her road out of the village was not through a state- run school, but Rahmani30, a free coaching school for underprivileged Muslim students set up by Maulana Wali Rahmani, a Muslim former politician and academician, in 2008.

Rahmani30 now mentors 850 students- girls and boys- in three cities, including Patna, Bihar’s capital. Chosen students live in the school’s rented buildings and cram for national entrance exams in engineering, medicine, and chartered accountancy. Many of them are first- generation learners, children of fruit vendors, farm workers, labourers and construction workers.

Some 600 alumni are already working as software engineers, chartered accountants and in other professions. Six are doctors.

Next year, Arzoo will join more than two million competitors- if not more- to compete for one of the 100, 000- odd seats that India’s 707 medical colleges offer every year.

” I am ready for the challenge. I want to become a gynaecologist,” she says.

Mohammed Shakir sees his Rahmani30 education as his path to a better life that will enable him to care for his depressed family.

Last April, the 15- year- old, and his friend embarked on a six- hour bus journey to Patna, travelling through a district hit by religious riots sparked by a Hindu festival procession. They traveled with a bottle of water and a few dates, spent the night in a mosque, sat for the Rahmani30 entrance exam, and passed.

” My parents were so scared, they said do n’t go. I told them,” The time is now. If I do n’t go now, I do n’t know what my future will be”, Shakir said.

For this teenager, who dreams of becoming a computer scientist, the fears over religious tension appeared to be the least of his worries.

I had informed my mother that I would come back after passing the exam. On the way, I wo n’t experience anything. After all, why should anything go wrong? In my village, Hindus and Muslims live together in perfect harmony”.

So what about the future of India’s Muslims- also divided on class, sect, caste and regional lines- in the world’s most populous country?

Mr. Salam discusses the concept of “lingering fear.”

” People complain about the Muslim community’s lack of jobs and inflation. But it’s just not about inflation and employment. It is about right to life”.

Similar fears are described in recent memoirs by young Muslims.

” Almost everyone has chosen a nation to flee to if the unavoidable occurs.” Some have got in touch with uncles settled in Canada, the US, Turkey or the UK, if they ever need asylum. Even someone like me, who felt safe even in times of communal violence, now worries about my family’s future in my homeland”, writes Zeyad Masroor Khan in his recent book City on Fire: A Boyhood in Aligarh.

Ms. Ahmad experiences a lot of uncertainty about the future in Agra.

” In the beginning I thought it]Muslim- baiting ] was fringe and it would pass. That was 10 years ago. I now feel that a lot has been irreparably damaged and lost.

All photographs copyright