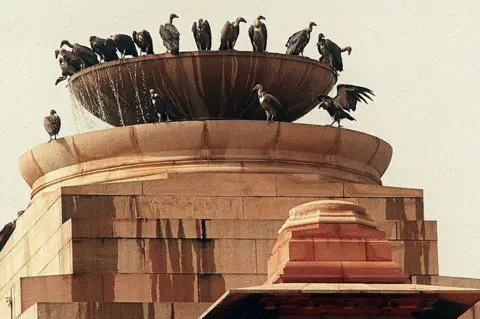

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe eagle was again a common and abundant animal in India.

The hunting birds hovered over sprawling waste, looking for cattle bones. They occasionally irritate pilots by sucked into aircraft engines during airports takeoffs.

However, more than 20 years ago, India’s birds started dying as a result of a drug used to treat sick calves.

By the mid-1990s, the 50 million-strong eagle people had plummeted to around zero because of paracetamol, a low non-steroidal drug for animals that is fatal to birds. Kidney failure and death were reported in animals fed on animal bones treated with the medication.

Since the 2006 ban on veterinary use of diclofenac, the decline has slowed in some areas, but at least three species have suffered long-term losses of 91-98%, according to the latest State of India’s Birds report.

And that’s not all, according to a new peer-reviewed study. The unintentional decimation of these heavy, scavenging birds allowed deadly bacteria and infections to proliferate, leading to the deaths of about half a million people per year over five years, says the study published in the American Economic Association journal.

AFP

AFPEyal Frank, an associate professor at University of Chicago’s Harris School of Public Policy, notes that “virtues are considered humanity’s sanitation services because they play an important role in removing dead creatures that contain germs and bacteria from our culture.”

Understanding the function birds play in human wellness “underlines the importance of protecting biodiversity, and not just the adorable and adorable. They all have a responsibility in our communities that affects how we live.

Before and after the hawk collapse, Mr. Frank and his co-author Anant Sudarshan compared the people death rates in American districts that had previously had low vulture populations to those that had previously low vulture populations. Additionally, they looked into sales of the rabies vaccination, wild dog counts, and levels of pathogens in the water supply.

They discovered that in areas where animals when thrived, human death prices increased by more than 4 % after eagle populations had collapsed and sales of anti-inflammatory medications had increased.

The researchers also discovered that corpse dumps were more prevalent in urban areas with significant animal populations.

AFP

AFPAccording to the authors, the loss of vultures added approximately 100, 000 human deaths annually between 2000 and 2005, resulting in more than$ 69 billion ( £53 billion ) in mortality losses or economic costs from premature deaths.

These incidents were brought on by the spread of disease and germs that eagles would otherwise have eliminated from the environment.

For instance, without birds, the stray dog people increased, bringing influenza to people.

Rabies vaccine selling rose during that time but were inadequate. In contrast to vultures, dogs were unable to remove rotting remains, causing drainage and weak leisure practices to spread pathogens and bacteria into drinking water. The amount of intestinal bacteria in the ocean has more than doubled.

The loss of a species provides a particularly striking illustration of the kind of hard-reverse and unexpected costs that people can incur, according to Mr. Sudarshan, an interact professor at the University of Warwick and co-author of the investigation.

Getty Images

Getty Images” In this case, fresh chemicals were to blame, but other people activities- habitat loss, wildlife trade, and then climate change- have an impact on animals and, in turn, on us. It’s crucial to comprehend these costs, target resources, and regulations aimed at preserving, especially these crucial species.

Of the vulture species in India, the white-rumped vulture, Indian vulture and red-headed vulture have suffered the most significant long-term declines since the early 2000s, with populations dropping by 98 %, 95 % and 91 %, respectively. The Egyptian vulture and the migratory griffon vulture have also declined significantly, but less catastrophically.

The 2019 livestock census in India recorded more than 500 million animals, the highest in the world. Vultures, highly efficient scavengers, were historically relied upon by farmers to swiftly remove livestock carcasses. According to researchers, the decline of vultures in India is the quickest for a bird species ever and the second-fastest since the passenger pigeon’s extinction in the US.

According to the State of Indian Birds report, India’s remaining vulture populations are now concentrated near protected areas where their diet consists of more dead animals than potentially contaminated livestock. These ongoing declines point to “ongoing threats for vultures, which is of particular concern given that vulture declines have negatively impacted human well-being.”

Experts warn that veterinary medications still pose a significant threat to vultures. The dwindling availability of carcasses, due to increased burial and competition from feral dogs, exacerbates the problem. Some vulture species ‘ nesting habitats may be hampered by quarrying and mining.

Will the vultures come back? It is difficult to say, though there are some promising signs. Last year, 20 vultures – bred in captivity and fitted with satellite tags and rescued – were released from a tiger reserve in West Bengal. More than 300 vultures were recorded in the recent survey in southern India. But more action is required.

Follow BBC India on YouTube, Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.