This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

For Vinesh Phogat, the year 2023 was crucial in every sense.

With just three months left for the World Championships and the Asian Games, the Indian wrestler would have been at the peak of her training regime right now. She calls it the “ultimate level”, the kind of training where the body begins to move automatically and you know in your bones what you have to do.

A two-time medal winner at the World Championships, this was Phogat’s chance to score a third.

But instead of mentally and physically preparing at a training camp, the wrestler has been living on a dusty pavement in India’s capital Delhi – where temperatures have crossed 42C – with “very little sleep” and subjected to “constant noise” for the past month.

Phogat is among a group of India’s most accomplished wrestlers who have been protesting after they accused their federation’s top official of sexual harassment and abuse of female wrestlers.

The wrestlers, including Olympic medallists, are demanding the resignation and arrest of the federation’s president, Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh. Mr Singh, who has been questioned by the Delhi Police, has denied the allegations and called the protests politically motivated.

The protests – Tuesday marks a month since they began – jeopardise the country’s prospects of winning a wrestling medal in the upcoming championships, leaving the athletes distraught and broken.

They may also end India’s dreams of another Olympics wrestling medal next year. The country has won seven Olympic medals in wrestling so far, seven of these since 2008.

“The entire country has pinned its hopes on us to get another medal – and we really want to – but here we are, sitting for 30 days with no resolution,” says wrestler Bajrang Punia, who won a bronze at the 2020 Olympics.

Every year, the International Olympic Committee earmarks a few events as qualification events for the games. For wrestling, the World Championship in September is that event, essentially making it a gateway for the Olympics, says sports writer Rudraneil Banerjee.

He adds that a world championship or a national game are also important in their own right – not just as qualifiers – as they are big events for any sport and player.

The athletes say they are continuing their training – which began in December – at the protest site but experts worry that this might not be enough.

“Wrestling is an extremely physically demanding sport. You have to be in extreme condition to be at the best level, and that requires you to be constantly in practice,” Mr Banerjee says.

He adds that without the necessary conditioning, a player is likely to lose in the first 30 seconds, “no matter what their skills are”.

Punia says that they have already missed out on some of the major tournaments, including an Asian ranking series, this year. “People say we are protesting for personal gains. But not getting to compete is the worst thing that could happen to a player.”

On an ordinary day, the wrestlers’ training would begin early – around 4-5am depending on the time zone – with some warm-up exercises. From there on, the routine looks different every day.

Some days, they practise weight training, on other days the focus is on cross-functional exercises to boost overall fitness levels. At other times, they would have trial matches to work on their technique and strategy.

“It’s a very dedicated life, you do not do anything at all. You train, sleep, eat, repeat,” Phogat says.

In the first few months of training for a competition, wrestlers build up their strength to be able to withstand the “brutal level” that awaits them. Mr Banerjee calls this “a time of focused intensity”, one that requires the athletes to concentrate only on discipline. Every part of the body needs to be strong, from physical power and mental well-being to technique. And every move, grunt and gasp is monitored to achieve that.

In the next few months, a wrestler’s body performs at the absolute limit of strength – what is called “explosive power”, which means projecting the maximum amount of strength in the minimum amount of time, Mr Banerjee says. This can be achieved only in very short bursts. And then there is the last month before the competition, where the body is given time to rest and recover.

Punia says this is important as it gives the body time to heal from injuries.

Given that the Asian Games and the World Championships are both in September, Mr Banerjee says the best scenario would be for the protests to be called off by the next week so that the wrestlers can go back into “absolute full training”.

“But even if they get three odd months of dedicated wrestling training, it still might not be enough to get them into the kind of conditioning they need to win,” he adds.

It’s a fear that haunts the athletes too as they continue protesting in Delhi.

Surrounded by hundreds of police officers and supporters, they hunker down inside a canopied structure made of blue tarpaulin sheets that serves as a tent.

The athletes are accessible through the day, meeting people, giving speeches and interviews. But at dawn – when most supporters are asleep – they briefly transition into wrestlers again.

Heaving with fatigue and with perspiration dripping off their foreheads, they train for an hour or two at a nearby centre. During practice, they remain dedicated and say they are still planning to compete. But they are also frustrated.

The time they get here is nothing compared with the dedicated hours of training at camp – and sometimes even this is interrupted by eager supporters. “In our hearts we know this level of training might not be enough but we are trying to do what we can,” Phogat says.

Their living conditions are also far from perfect, making it harder to maintain focus.

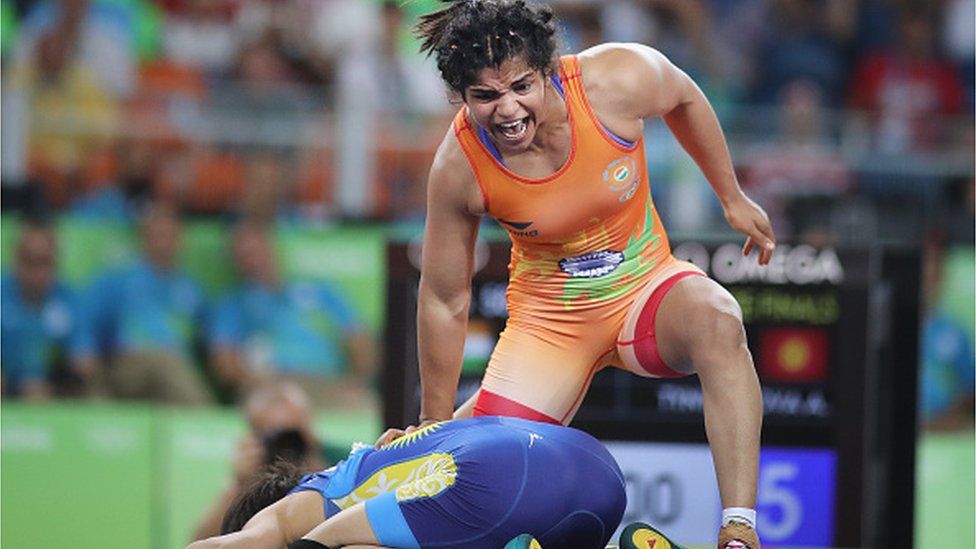

“Even training camp life is hard. But that’s the life we know,” says Sakshi Malik, the first Indian woman to win an Olympic wrestling medal in 2016. “But living here, with no proper food or sleep and hardly any rest, is something we never thought we’d have to do.”

Punia adds that the point is not losing, it’s about being able to give their best shot.

“But how do we do that when we cannot train properly?” he asks.

From a sporting point of view, Banerjee says that the wrestlers’ inability to compete might not completely dampen India’s prospects as the country has a pool of talented wrestlers who can be trained to compete.

“But the point is that this protest is about justice and why due process was not followed for such serious allegations,” he adds.

The wrestlers, too, admit they feel “rather dispensable”, but say that they will continue protesting until their demands are met even if their careers suffer.

“It’s not a wrestler’s job to speak out. Our job is to train, play and win. But speaking out is our responsibility and we’ll keep at it,” says Malik.

For Phogat though, it will still be a hard pill to swallow. “Because we could’ve done it, won that medal,” she says.

“We were at our best and not getting to play at our peak will leave us all a little dead inside.”

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Read more India stories from the BBC:

-

-

1 February

-