This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

How do you teach millions of people family planning?

By getting them to say the word condom again and again till it shatters any form of shame or stigma around its use.

Risqué as it might sound, that is exactly what advertisement writer Anand Suspi did 18 years ago when his team at Lowe Lintas designed the Condom Bindass Bol (Say Condom Freely) campaign in India.

Launched in 2006, the public awareness campaign made in collaboration with the Indian government was created to overturn a decline in the sales and use of condom in eight states in northern India which together comprised nearly half of the country’s condom market at the time.

The campaign featured comical scenarios where a shy man – ranging from a sheepish cop getting some downtime at a dingy police station, to a grubby lawyer surrounded by men outside court – is encouraged by his peers to say condom, loudly and clearly, in public.

“Bol, bindass bol (Just say it and say it freely),” one of the them would urge him till he finally blurted out the word.

The advert – which went viral and even won a UN award – was among a series of campaigns on family planning in India which have used witty slogans and messages to emphasise problems of rapid population growth and promote healthy sex practices.

The slogans first emerged sometime in the 1950s, when India opened a new department devoted to family planning – the first in the world – and aggressively began promoting the use of contraception and methods like sterilisation to bring down its burgeoning population.

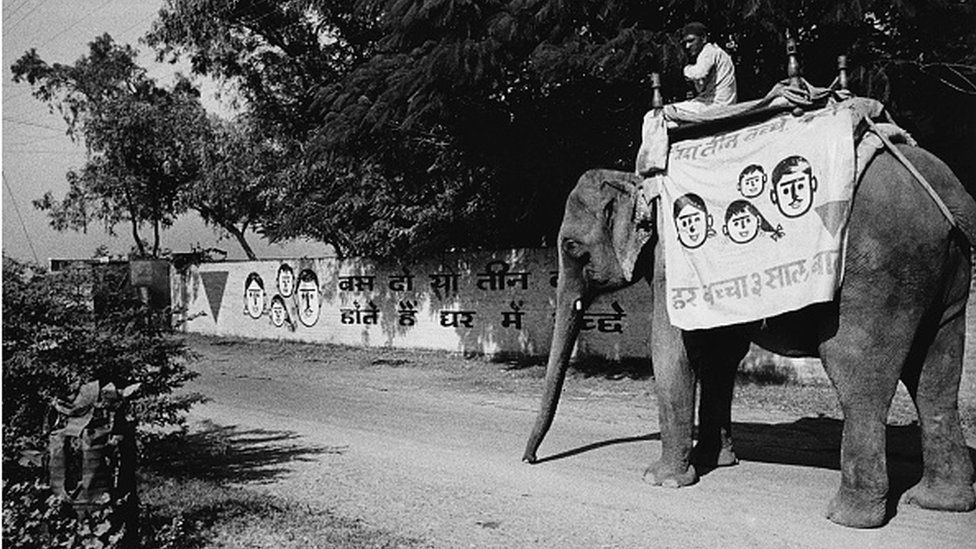

Catchy one-liners such as Hum Do Humare Do (We are Two, will have Two Children) and Chota Parivar, Sukhi Parivaar (Small Family is Happy Family) urging people to have fewer children were broadcast widely through TV and radio programmes, posters, and every other medium possible. Sometimes, even elephants were used to spread the message in the remote pockets of the country.

The campaigns – which continue to this date – have become synonymous with the definition of family planning in India.

Experts say they have also helped create a new vocabulary for sensitive topics like contraception and birth control, which are still considered taboo in vast swathes of the country.

“Men everywhere crack the foulest jokes and find it funny but the minute you utter the word condom they get embarrassed,” says Mr Suspi. Studies have also found that Indian men identify shyness as the reason they are unwilling to speak about safe sex practices in their relationships.

Sashwati Banerjee, a public health expert who also worked on the campaign, says the idea behind Bindass Bol was simple: to get men to ask for a condom without hesitation. Because condom, she says, is not delicate word – a bad word – that needs to be wrapped in innuendos and said in hushed tones. Condoms are used by everyone, should be used by everyone.

To execute this, the team partnered with over 40,000 condom marketers and chemists to enhance retail visibility of the contraceptive, so that men would generally become more comfortable about using it.

“But what eventually worked was some good old humour – you first have a good laugh and then the message seeps in,” Mr Suspi says.

While the government and private organisations spent much time and money on the ad campaigns, not all of them were successful – and some even generated backlash.

Critics say that a lot of the programmes were also ineffective because they focussed almost entirely on women and continued to keep men on the margins.

“Back in the day, women had no agency when it came to the choice of contraceptive, if at all it had to be used,” says Radharani Mitra, the National Creative Director and Executive Producer of BBC Media Action.

So women ended up bearing the entire burden of contraception, but men – who actually control decision-making in most homes – remained clueless and resistant to family planning practices.

It’s a trend that continues – between 2019 and 2021, nearly 38% of women surveyed nationwide for the fifth National Family Health Survey (NFHS) had undergone sterilisation, compared to just 0.3% of men who had undergone a vasectomy.

Anand Sinha, a public health expert, says that “slogans cannot replace traditional counselling and the larger need for overall social development”.

But they did help in changing social norms and creating a positive momentum, he adds.

During the 1975 Emergency – when civil liberties were suspended – India’s family planning campaign suffered a setback.

During this time, the government forced millions of women, men and even children to undergo sterilisation. “The measures gave the campaign a bad name and suddenly, people were scared of the very idea of contraception,” Mr Sinha says.

For many years after that, the biggest challenge was to reimagine family planning and give it a “more acceptable, a warmer and a friendly face”.

Around this time, private sector firms selling condoms began looking for more creative ways to sell contraceptives to young couples. As a result, campaigns became sexier and more relatable.

A renewed and bigger marketing of contraceptive methods began from the late 1980s, when HIV/Aids became a huge threat in the West, sparking fears of its spread in a densely-packed country like India, says Ms Mitra

“The topic of sex was brought out more into the open and social campaigns on condoms became common.”

The most memorable of these was the condom ringtone in 2008, which was part of a 360-degree “condom normalisation” campaign.

The campaign, led by BBC Media Action and funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, was part of the larger programme on safer sex for HIV prevention in India.

It used a mobile ringtone in which the word “condom” was repeated over and over in rich, neatly stacked harmonies, giving it the feel of a catchy a cappella arrangement. The campaign also featured a funny video which showed an Indian man who is mortified when his phone begins to buzz with the condom ringtone at a wedding ceremony.

Ms Mitra says the ringtone went viral and had nearly 480,000 requests for download, getting played by NPR in the US and across the world from Japan to Indonesia, from South America and even Europe.

“It made the headlines all over the world, won awards everywhere, but it had real impact, which is what’s most important.”

Ms Banerjee says that behaviour change is like a big jigsaw puzzle: “You kind of pull all the pieces together, and then a picture forms,” she says.

“And sometimes, just sparking a conversation can help change attitudes.”

BBC News India is now on YouTube. Click here to subscribe and watch our documentaries, explainers and features.

Related Topics

-

-

14 November 2014

-

-

-

27 June 2022

-

-

-

12 July 2011

-