By Hyojung Kim, BBC Korean

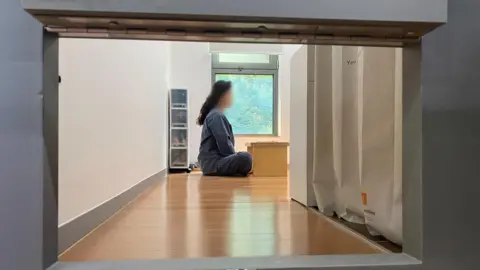

Korea Youth Foundation

Korea Youth FoundationA lock feeding opening serves as the only connection between the little rooms at the Happiness Factory and the outside world.

These tissues, which are no bigger than a store shelf, have no phones or laptops within, and their residents just have plain walls for privacy.

Residents of the prison in South Korea may wear orange prison clothing, but they are not prisoners. They have been there for a” confinement experience.”

Most of the people present have a baby who has completely withdrawn from society and have experienced how it feels to be isolated from the outside world.

Lone- confinement cell

Children of lonely young individuals like these residents’ are referred to as depression, a term used in Japan in the 1990s to describe extreme social withdrawal among adolescents and young adults.

Next time, a North Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare study of 15, 000 19- to 34- yr- olds found more than 5 % of respondents were isolating themselves.

If this is delegate of the wider community of South Korea, it may mean about 540, 000 people were in the same position.

Kids have been taking part in a 13-week parental training program that is being run by non-governmental organizations like the Korea Youth Foundation and the Blue Whale Recovery Centre since April.

The purpose of the program is to teach individuals how to speak with their kids more effectively.

The three-day program includes a stay in a hospital in Hongcheon-gun, Gangwon Province, where participants spend day in a place that resembles a solitary-contained body.

The idea is that parental separation will help them understand their kids more.

Emotional confinement

Jin Young- hae’s child has been isolating himself in his home for the past three decades.

But since wasting time in captivity herself, Ms Jin ( never her real name ) understands her 24- yr- old’s “emotional jail” a little better.

” I’ve been wondering what I did bad… it’s painful to think about”, the 50- yr- old says.

” But as I started reflecting, I gained some clarity”.

Reluctance to speak

Her brother has always been talented, Ms Jin says, and she and his parents had high expectations of him.

But he frequently ill, struggled to maintain friends, and finally developed an eating disorder, which made schoolwork challenging for him.

When her son began attending college, he seemed to be doing effectively for a phrase- but one time, he entirely withdrew.

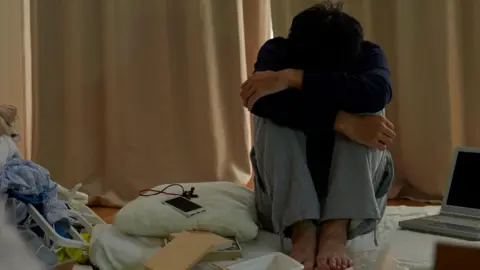

Seeing him locked in his place, neglecting personal health and dishes, broke her heart.

But her child is reluctant to talk to her about what is really bad despite the fact that he may have experienced stress, difficult relationships with family and friends, and disappointment at not being accepted into a prestigious school.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen Ms. Jin arrived at the Happiness Factory, she read notes left by other lone young people.

” Reading those notes made me realise,’ Ah, he’s protecting himself with silence because no- one understands him ‘”, she says.

For her 26-year-old son, who had been disconnected from communication with the outside world seven years ago, Park Han-sil ( not her real name ) came here.

He now rarely leaves his room after escaping home a few times.

Ms. Park took her son to a counselor and doctors, but his son refused to take the mental health medication he had been prescribed and became obsessed with video games.

Interpersonal relationships

Ms Park is still trying to reach her son, but she has started using the isolation program to help him understand his feelings.

” I’ve realised that it’s important to accept my child’s life without forcing him into a specific mould”, she says.

There are a number of factors that, according to research from the South Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, cause young people to cut themselves off.

According to the ministry’s survey of 19- to 34- year- olds, the most common reasons are:

- difficulties finding a job ( 24.1 % )

- issues with interpersonal relationships ( 23.5 % )

- family problems ( 12.4 % )

- health issues ( 12.4 % )

South Korea’s government released a five-year plan to address this year, which has one of the highest suicide rates in the world.

Ministers made the announcement that people between the ages of 20 and 34 would receive state-funded mental health check-ups every two years.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Japan, the first wave of young people isolating themselves, in the 1990s, has led to a demographic of middle- aged people dependent on their elderly parents.

Some older people have fallen into poverty and depression, and some of their adult children have been forced to do so by their only pensions.

Young people’s anxiety is amplified by Prof. Jeong Go-wooon’s sociology department at Kyung Hee University, especially in times of economic stagnation and low employment, according to Prof. Jeong Go-wooon from Kyung Hee University.

The notion that a child’s successes are a result of a parent’s care causes entire families to become isolated.

And many parents perceive their child’s struggles as a failure in upbringing, leading to a sense of guilt.

According to Prof. Jeong, “parents in Korea often express their love and feelings through real-world actions and roles rather than verbal expressions.”

A Confucian culture that emphasizes responsibility is typical of parents who help pay their children’s tuition through hard work.

This cultural emphasis on hard work may be a sign of South Korea’s explosive economic growth in the second half of the 21st century, when it emerged as one of the world’s largest economies.

However, according to the World Inequality Database, the country’s wealth inequality has worsened over the last three decades.

Korea Youth Foundation

Korea Youth FoundationKim Ok- ran, director of the Blue Whale Recovery Centre, claims that many parents also end up abusing those who are close to them because they believe that controlling young people is a “family problem.”

And some people ca n’t even talk to close relatives about their situation because they fear being judged.

They ca n’t bring the issue up in front, Ms. Kim says, which will make the parents as well be isolated.

” Often, they stop attending family gatherings during holidays”.

‘ Watching over ‘

The Happiness Factory’s clients are still eagerly awaiting the day when their children can resume a normal life.

Asked what she would say to her son if he came out of isolation, Ms Jin’s eyes fill with tears.

” You’ve been through so much”, she says, voice trembling.

” It was hard, was n’t it?

” I’ll be watching over you.”

If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this article you can find sources of help from BBC Action Line.