A Sufi shrine frequented by Indians of all faiths made headlines recently after a top political leader said that he wanted to “liberate” it for just Hindus. The BBC’s Cherylann Mollan visited to understand what the controversy was about.

The ascent is no easy feat, with some 1,500 rock-cut steps separating the devout from their destination: a Sufi saint’s tomb that has become a seat of faith, legend and disputed history.

The Haji Malang dargah (shrine), sitting on a hill on the outskirts of Mumbai in the western state of Maharashtra, is said to house the tomb of an Arab missionary who came to India more than 700 years ago. Like many other Sufi shrines across India, the dargah is seen as a symbol of assimilation and tolerance, despite being at the centre of a religious dispute.

When I visited, both Hindus and Muslims were offering flowers and a chadar – a piece of cloth offered as a symbol of respect in Sufi traditions – at the saint’s tomb. The belief is that any wish asked for with a “pure heart” will be granted.

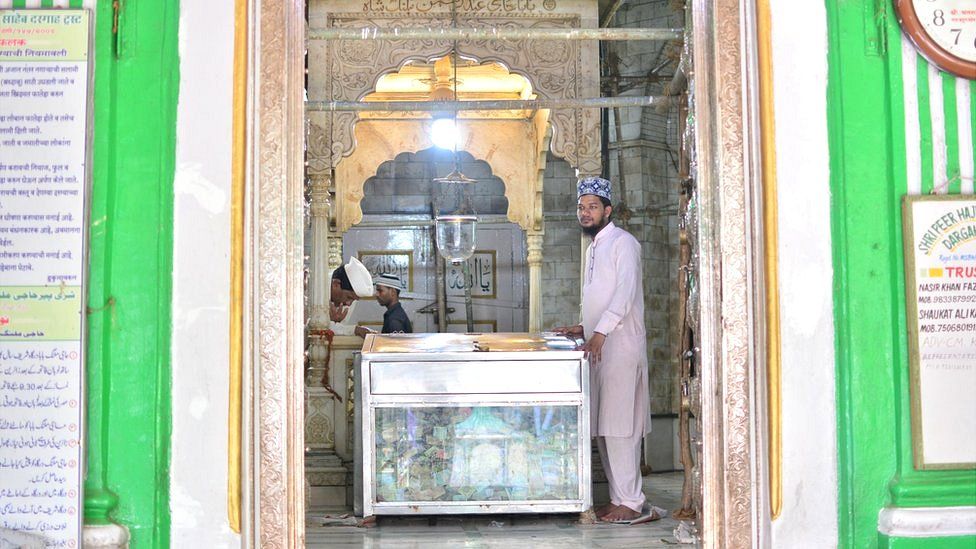

The shrine’s managing board mirrors this sense of respectful co-existence – while two of its trustees are Muslims, its hereditary custodians are from a Hindu Brahmin family.

But earlier this month, Maharashtra Chief Minister Eknath Shinde stirred controversy by reviving a decades-old claim at a political rally. He asserted that the structure, traditionally considered a dargah, was a temple belonging to Hindus, and declared his commitment to “liberating” it.

Mr Shinde did not respond to the BBC’s request for comment.

His claim comes at a time when some prominent mosques and Muslim-made monuments in India are mired in disputes over claims that they were constructed by demolishing Hindu temples centuries ago.

In the 1980s, Mr Shinde’s political mentor, Anand Dighe, spearheaded a campaign to “reclaim” the Haji Malang dargah for Hindus. In 1996, he reportedly led 20,000 workers from the Shiv Sena party inside the dargah to perform a pooja (a Hindu act of worship).

Since then, Hindu hardliners, who refer to the structure as Malanggad, have continued the practice of performing pooja at the shrine on full Moon days, occasionally leading to clashes with Muslim devotees and locals.

But political observers say that Mr Shinde’s stance may have less to do with faith and more to do with optics. Dighe’s campaign had bumped up his appeal among Hindu voters in Maharashtra state.

“Mr Shinde is now trying to position himself as the ‘Hindu saviour’ of Maharashtra,” says Prashant Dixit, a former journalist.

Separate from the national election, Maharashtra – India’s wealthiest state – will vote for the state assembly later this year. Securing support from the Hindu majority is crucial for Mr Shinde, given the state’s distinctive political landscape, says Mr Dixit.

Elections in Maharashtra are usually a four-way contest between the nativist, Hindu nationalist Shiv Sena and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the centrist Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) and Congress, each with their own share of core voters.

But Mr Shinde faces an additional complication – in 2022, he and his supporters defected from the erstwhile Shiv Sena.

The rebellion toppled the then-triparty government – an unlikely coalition of the Shiv Sena, Congress and NCP – and forged a new alliance with the BJP to form the new government.

“But while lawmakers might change parties, it’s hard to get core voters to switch loyalties,” Mr Dixit says. “By raising the dargah issue, Mr Shinde is hoping to appeal to the emotions of the core voters of the erstwhile Shiv Sena and consolidate the Hindu vote bank,” he says.

Hindu devotees the BBC spoke to had mixed reactions to Mr Shinde’s comments.

Kushal Misl, for instance, sees Mr Shinde as articulating what has long been on his mind – a belief that the shrine originally belonged to a Hindu saint and was later taken over by Muslims during invasions in India.

Rajendra Gaikwad shares a similar view but says that he feels uneasy about the ongoing debate. “Whatever is happening in India right now is very bad,” he says, and underscores his belief that for him, “all gods are one”.

Abhijit Nagare, who goes to the shrine every month, says that it doesn’t matter to him which religion the structure belongs to – he likes to visit because he feels at peace there.

Nasir Khan, one of the shrine’s trustees, told the BBC that the controversy had led to a dip in the number of devotees visiting the shrine. “People come with their families and don’t want to be hassled by miscreants,” he said.

The controversy is also hurting local businesses.

The structure sitting atop the 3,000ft (914m) hill doesn’t stand alone. The elevation is punctuated with houses, shops, and restaurants carved into the stone and rock over the years.

Mr Khan says that about 4,000 people, both Hindus and Muslims, live there. The locals depend on tourism to make a living, but it’s a tough existence.

Locals told the BBC that they struggle to get basic amenities like potable water, especially in the gruelling summer months.

“Water has to be rationed. Each family is given just 10 litres of water per day,” says Ayyub Shaikh, a local village council member.

The hill also doesn’t have a proper hospital, school or an ambulance.

“An educated person would not want to live here; there’s nothing for them to do,” says 22-year-old tuk-tuk driver Shaikh, who asked for only his first name to be used.

“All politicians want to do is play games to get votes. Nobody really cares about what the people want.”

The sentiment is echoed by numerous locals.

“Hindus and Muslims have co-existed in harmony on this hill for centuries,” Mr Shaikh says. “We celebrate festivals together and support each other in times of need.

“Nobody else stands by us – so why would we fight among ourselves?”

Read more India stories from the BBC: