Sanjaya Dhakal / BBC Nepali

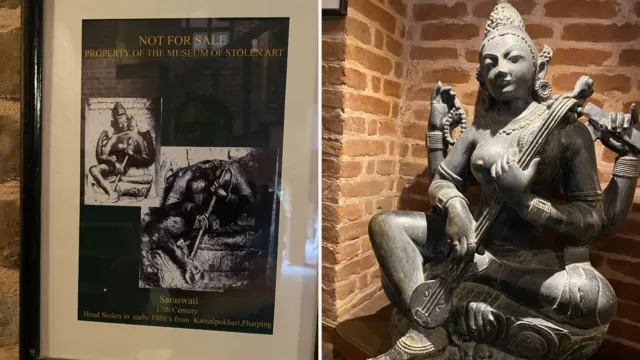

Sanjaya Dhakal / BBC NepaliA mysterious building with a peculiar title, the Museum of Stolen Art, stands along a small city in Bhaktapur area, Nepal.

Inside it are areas filled with statues of Nepal’s spiritual gods and goddesses.

Among them is the Saraswati artwork. The Hindu goddess of wisdom, perched atop a flower, holds a book, meditation stones, and a traditional device known as a goddess in her four arms.

The memorial is a fake, like all the other carvings in the room.

One of 45 duplicates in the museum, which will have a dedicated location in Panauti, is scheduled to open to the public in 2026.

Rabindra Puri, a naturalist from Nepal, is directing a campaign to retrieve lots of Nepal’s stolen artifacts, many of which are dispersed across museums, auction houses, or private choices in countries like the US, UK, and France.

He has hired a half-dozen artisans to make replicas of these figures over the past five decades, each requiring between three and a year to complete. The museum has not been given any money by the authorities.

His goal is to get these stolen objects back in exchange for the duplicates he has made.

In Nepal, like statues remain in churches all across the country and are regarded as part of the region’s “living society”, more than mere masterpieces, says Sanjay Adhikari, the director of the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign.

Visitors worship many of them daily, with some devoted to giving foods and flowers to the gods.

” An old woman told me she used to worship Saraswati daily”, says Mr Puri. She felt more unhappy when she learned that the idol had been stolen than when her husband passed away.

These statues are often guarded, leaving them wide open for thieves, which is why it is also popular for followers to contact them for blessings.

Sanjaya Dhakal / BBC Nepali

Sanjaya Dhakal / BBC NepaliNepal has categorised more than 400 documents missing from churches and monasteries across the country, but the amount is very likely to be an overlook, says Saubhagya Pradhananga, who heads the standard Department of Archaeology.

As Nepal’s isolated state opened up to the outside world, lots of documents were looted from Nepal between the 1960s and the 1980s.

Some of the country’s most effective executives from the time were thought to be responsible for some of these thefts, with many claiming to have smuggled them abroad to craft collectors and pocketed the profits.

Nepalis were generally unaware of their lost art and where it had vanished for decades, but that has changed, particularly since the establishment of the National Heritage Recovery Campaign in 2021, a motion led by citizen activists to regain lost treasures.

According to activists, many of these gods are currently housed in museums, auction houses, or private archives in Western nations like the US, UK, and France.

Additionally, they cooperate with unusual governments to persuade local authorities to return the items.

Shocked to discover it in an American gallery

But there are many barriers. The Taleju Necklace, dating up to the 17th century, is a case in point.

The enormous gold-plated necklace with precious stones vanished from the Temple of Taleju, Nepal’s queen known as the chief safe deity, in 1970.

The temple’s removal on the ninth day of the Dashain Festival, which is only once a year, was all the more surprising.

Some in Nepal had no notion where it might have gone until three years ago, when it was seen in an unlikely location- the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s also unclear how it might have been stolen.

Dr. Sweta Gyanu Baniya, a Nepali intellectual based in the US, reported that when she saw the necklace, she fell to her knees and began crying.

” It’s not just a jewellery, it’s a part of our queen who we devotion. I felt like it should n’t be here. It’s spiritual”, she told the US school Virginia Tech.

Allow Twitter content?

The Chief Priest of the Temple of Taleju, Uddhav Karmacharya, says,” We were shocked after so many times that it was on display in an American museum.

According to him,” The day it is repatriated will be the most important moment in my life,” he has submitted records proving its origin to the Nepali government.

The Alsdorf Foundation, a secret US base, gave the necklace, according to the Art Institute of Chicago. The exhibition confirmed to the BBC that it has spoken with the government of Nepal and is awaiting more information.

But Pradhananga said Nepal’s Department of Archaeology had provided enough information, including archive files. Additionally, King Pratap Malla wrote that the necklace was made especially for the Goddess of Taleju.

It’s these “tactics of wait” that usually “wear down politicians”, says one advocate, Kanak Mani Dixit.

They “like to use the term provenance” when they request proof from us. Instead of Nepal themselves, the burden is placed on us to show that it belongs to them.

But nevertheless, some progress has been made, and about 200 documents have been returned to Nepal since 1986 – though most exchanges took position in the past century.

Nearly 40 years after it vanished from a sanctuary, Laxmi Narayan, a divine hero of Hindu deities, has returned to Nepal from the Dallas Museum of Art.

80 deported documents are now housed in a specific museum at the National Museum of Nepal, pending repair before being returned to their proper locations. Since 2022, there have been six idol returns to the area.

Sanjaya Dhakal / BBC Nepali

Sanjaya Dhakal / BBC NepaliThe Laxmi Narayan hero has been brought back to the temple where it was actually taken, and it is still revered every day, just like it was when the original idol was created in the 10th century.

However, some worshippers are now much more suspicious, so putting these deities in iron cages to prevent them from disappearing is a wise decision.

But, Mr. Puri hopes that his museum’s cabinets will finally be completely wiped clean.

” Only return our gods,” I urge galleries and anyone else holding the stolen artifacts. he says. ” You can have your art”.