So this is going to be it for the next few days: A tiny, bland room without a bed or wardrobe. The mattress on the floor will have to suffice.

Like everyone else in this Buddhist monastery, from here on I’m wearing a simply-cut robe of rough linen, which just barely keeps me warm in the cool mountain temperatures.

Still, I have a bit of an advantage over the permanent residents: My chamber has floor heating and a small bathroom with a toilet – sheer luxury in the Beopjusa Temple in the heart of South Korea. I have come here to spend two days with Buddhist monks, to meditate and pray.

Dubbed “Templestay”, the programme offered by some 130 South Korean monasteries to both locals and tourists from around the world is marketed as “a wonderful way to recharge oneself”.

Interestingly enough, the idea was born during the 2002 World Cup, when hotel accommodations became tight and temples offered to host football fans.

Since then, hundreds of thousands of visitors, mainly Koreans, have taken up the offer every year.

Down on the knees

Put politely, the daily routine in a Buddhist monastery takes some getting used to. The alarm clock goes off at 3am. Anyone who oversleeps will soon be standing straight up in bed from the pounding of the mighty drum sounding through the temple.

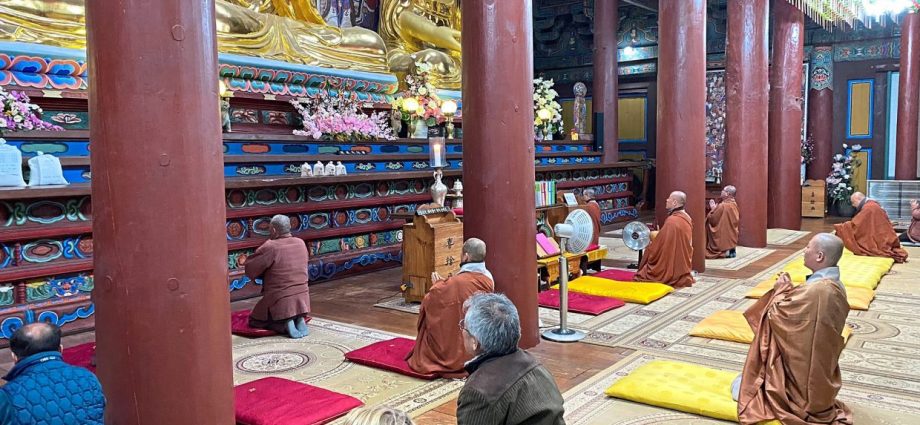

It’s the call to the first morning prayer ceremony, the “Yebul”, in the grand hall. The Yebul consists of 108 “Baekpalbae” – dropping to the knees and standing back up again – to honour the teachings and sufferings of the Buddha.

Because everyone knows what torture the kneeling-and-standing exercise can be, nobody will hold it against visitors – I being one of them – if they give up with severe back pain after performing less than half the required Baekpalbae.

During Templestay, it’s up to the guests whether they participate in every ceremony and meditation or choose to have some time for themselves.

According to Visit Korea, other activities can include communal work and learning how to make a lotus lantern, “a form of Buddhist art”.

Vegan cuisine

A good two hours’ drive south-east of the capital Seoul, Beopjusa Temple is beautifully nestled on the slopes of Songnisan Mountain in the national park of the same name and very popular with tourists.

The monastery became famous in part thanks to its 33m-tall Buddha statue which towers over a total of 60 buildings.

But visitors also come to see the temple’s five-storey wooden pagoda, the only one in South Korea that looks exactly as it did when it was built about 1,500 years ago.

In its heyday, as many as 3,000 monks lived at Beopjusa Temple.

Today, at most 40 remain, still following the old strict rules and rituals.

Prayer and meditation are only interrupted by work and the three meals each day, which are strictly vegan.

Three times a day the monks are served vegetables, rice and kimchi, washed down with water or, occasionally, tea. They’re eating in strict silence.

At sunset Jl-o, one of the leaders of the temple, invites guests for tea.

A quiet, calm man in his mid-40s, Jl-o gladly answers visitors’ questions.

What he relates shows that time hasn’t stopped in Beopjusa.

While in earlier times the monks used to exist on food and donations from people in the area, now the monastery’s income is derived from the temple property itself, parking fees and admission tickets – enough to comfortably make ends meet.

While outside the lights of the dormitories are turned off at 9pm – signalling bed time for the young monks – the tea party with Jl-o isn’t over yet.

“Like my older brothers I don’t have to go to bed so early,” he says with a laugh. Sometimes they will watch a football match on the TV.

“We turn the volume down very low so that we don’t wake the others,” he explains.

According to Seoul National University Hospital scientists, temple stays have a definite therapeutic effect.

A three-year study concluded that people who made even a short temple visit felt happier and less fearful or stressed out afterwards.

Jl-o can confirm this without reservation. Before he joined the monastery, he worked as a camera man, but at some point he asked himself the question, “what is the purpose of this hectic and consumer-oriented life?”

Sometimes Jl-o will meet up with friends from his earlier life.

“Then I am happy, but I do feel that we are living in two worlds,” he says. – JOACHIM HAUCK/dpa