Millions who survived Myanmar’s strongest cyclone are now struggling to rebuild their lives after the government cut off access to affected areas, including for aid groups.

The move has “turned an extreme weather event into a man-made catastrophe,” Human Rights Watch has said.

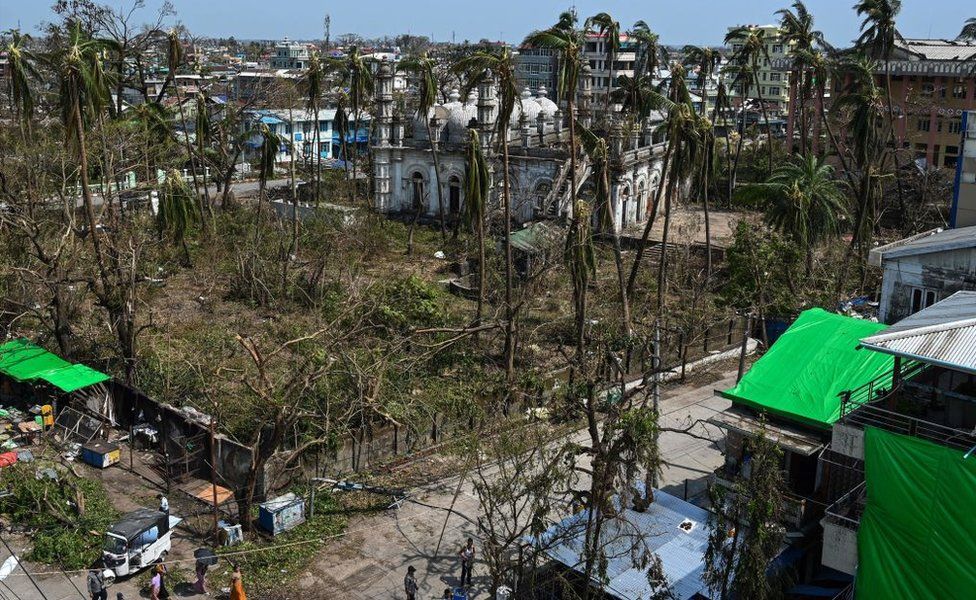

Cyclone Mocha hit on 14 May, wreaking havoc and killing hundreds.

The BBC spoke to families who are reeling from dwindling aid a month after their homes were destroyed.

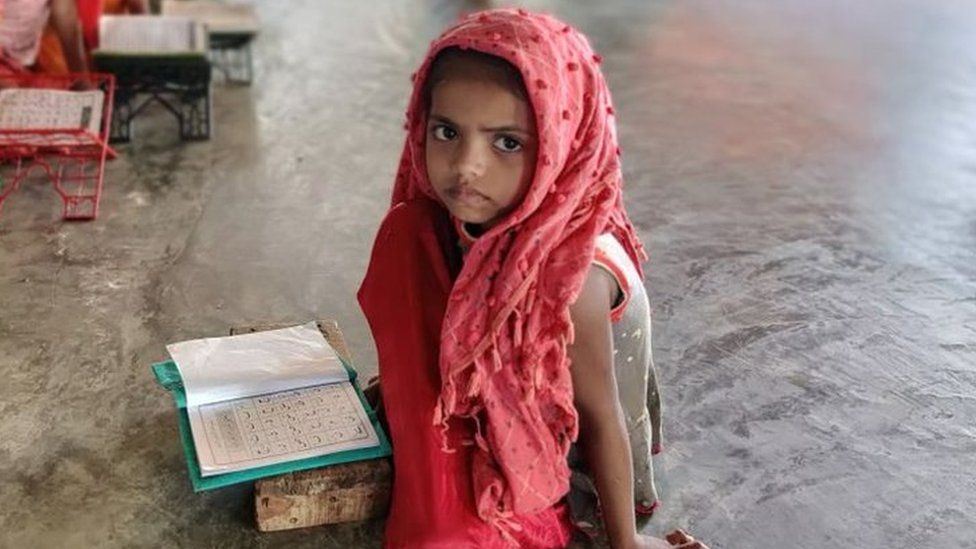

There isn’t enough water or food, and finding either has been much harder with the monsoon under way, says Aye Kyawt Phyu, who lives in Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine state, which was ravaged by the storm. “It’s raining all week. We are struggling every day. The children are studying in a school with no roof.”

‘When the storm hit, all the houses collapsed. There is nowhere to stay,” said San San Htay, who also lives in Sittwe. “When it rains now, I am sitting in the rain. I can’t even sleep.”

Only a fraction of damaged homes have been repaired, the UN’s humanitarian office said. The junta says the cyclone killed 145 people, but the clandestine National Unity Government estimates that the toll was closer to 500. The Arakan Army, an ethnic insurgent group in Rakhine, said that the storm destroyed more than 2,000 villages and 280,000 homes in the state.

Of the 5.4 million people in Myanmar who were in Cyclone Mocha’s path, nearly 3.2 million are considered “most vulnerable” according to the UN. Rakhine, where Aye Kyawt Phyu and San San Htay live, is one of the country’s poorest states. Some 78% of its population lived below the poverty line as of 2019, according to the World Bank’s last estimate.

“We want Myanmar’s government to allow aid from outside,” says Aye Kyawt Phyu. In the immediate weeks after the storm, she says they received some rice, clean water and oil from outside.

Aid kept trickling in until 8 June, when Myanmar’s army rulers, or junta as they are known, banned transportation for aid groups operating in the area, making it impossible for them to deliver aid.

Officials never explained why they did this. But a Rakhine government spokesman told local media that they wanted to manage the distribution of aid, which he claimed had not been administered fairly.

“NGOs are only interested in helping the Muslim community,” he was quoted as saying. This is a reference to the Muslim Rohingya community, the majority of whom live in Rakhine.

Successive governments in Myanmar, a predominantly Buddhist country, have denied the Rohingya citizenship and see them as unauthorised immigrants from neighbouring Bangladesh. The UN estimates that more than half a million of them still live in northern Rakhine, although many have fled the country because of persecution.

The spokesman alleged that, “Even though these international groups say they are donating to Mocha [victims], frankly speaking, the Rakhine community does not receive it.”

Aid groups have not responded to the allegation, but told the BBC that the Rohingya’s ethnicity could have played a role in the decision.

“It is certainly our experience that the Myanmar military puts significant barriers… [on our efforts] to help Rohingya and have actively diminished the human rights of the communities,” said Claire Gibbons from Partners Relief & Development, a non-profit group that works in Myanmar.

Rohingyas in Rakhine say life in the aftermath of the cyclone has been extremely difficult. There has also been a decades-long conflict between the Buddhist-majority Rakhine ethnic group and the Rohingya.

“All our houses were destroyed, and some people are living in tents near the sea while others are in their damaged houses,” said Khadija, who wished to use a pseudonym. She lives in a coastal village called Dapaing.

Since the cyclone, many locals, including women in labour, have died on the way to hospital because if often took time to find transport, she added.

This is not the first time the junta has suspended aid. They did the same in the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis in 2008, when more than 100,000 people were killed.

Ms Gibbons said another possible reason for the army to do so again was that it preferred to control the flow of humanitarian aid to the heavily sanctioned country.

“They also aim to benefit from aid support, as they did when Cyclone Nargis struck. Some of the aid received from different countries ended up in the market, allowing them to make money from it,” she said.

In the wake of the latest ban, there have been calls for international NGOs to reduce what some have called their “overreliance” on the junta, which they say has hampered the international response to the cyclone.

Local aid workers say international groups should instead work more closely with locals who have more boots on the ground – some even suggest the armed resistance groups as possible partners. The Arakan Army, for instance, has established its own humanitarian wing in response to the cyclone.

Meanwhile, Khadija and other cyclone survivors continue to live with uncertainty over when help will arrive.

“We don’t know what will happen to us in this very difficult time,” she says. “We don’t know if we will keep living with hunger, or die.”

Related Topics

-

-

25 August 2022

-

-

-

21 December 2012

-