“CANNOT MAKE ENDS MEET”

Pakistan consistently ranks near the bottom of global gender parity indexes, and girls are often viewed as a financial burden because of the bride-price parents pay when they are married.

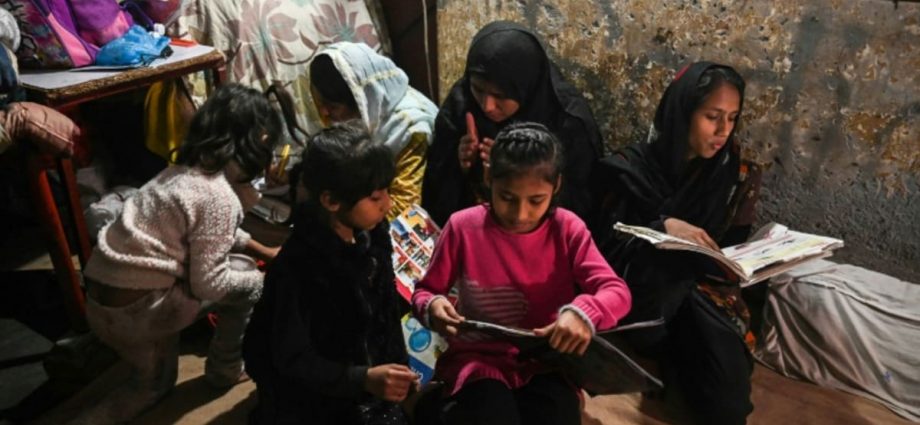

Amin wanted his six daughters to be educated, hoping they would lift the family out of generational poverty.

The household began to struggle in 2015, when Amin was injured in a road accident, forcing him to give up a relatively good wage as a labourer and take up a more sedentary, low-paying job.

He then told his wife she could work for the first time, but even with the extra income the family could not manage in the face of skyrocketing inflation.

“We had to force Nadia to drop out after completing fifth grade,” he says, his voice cracking with emotion.

As the eldest, Nadia was often tasked with helping care for her younger siblings, which left her unable to keep up with homework and she was ordered to repeat school years, a not uncommon situation in Pakistan.

The nominal school fees for the other five daughters are paid for by Miraj’s employer, but with finances precarious there is a risk that Nadia’s 13-year-old sister could be next to leave school.

Clearing up after making dinner for the family, Nadia collapses from exhaustion on the floor of a humble two-roomed rented home, as her sisters go about their homework.

“We cannot make ends meet. That’s why I give whatever salary I get to my mother,” Nadia says, adding that by shouldering some of the burden for her parents she may help her sisters have a brighter future.

Pakistan’s president on Wednesday (Feb 22) said half of the country’s children aged between five and 16 were at risk of entering the workforce or of begging.