SINGAPORE: In a finding that impacts how cheese can be marketed in Singapore, the Court of Appeal on Friday ( Nov 22 ) ruled that Parmesan is not the same as Parmigiano Reggiano.

According to Justices Tay Yong Kwang, Belinda Ang, and Judith Prakash, Singapore’s users do not believe Parmesan cheese to be made only in the specific region of Italy where Parmigiano Reggiano cheese is produced.

Instead, local customers have been influenced by how Parmesan is promoted and sold in Singapore as a butter that can and does come from abroad.

The Court of Appeal gave its decision after an appeal by Fonterra Brands ( Singapore ) Pte Ltd, a , subsidiary of a cooperative owned by 10, 000 dairy farms in New Zealand.

Fonterra, which sells different types of cheese under the Perfect Italiano brand, was contesting a lower court’s finding that” Parmesan” is a translation of” Parmigiano Reggiano”.

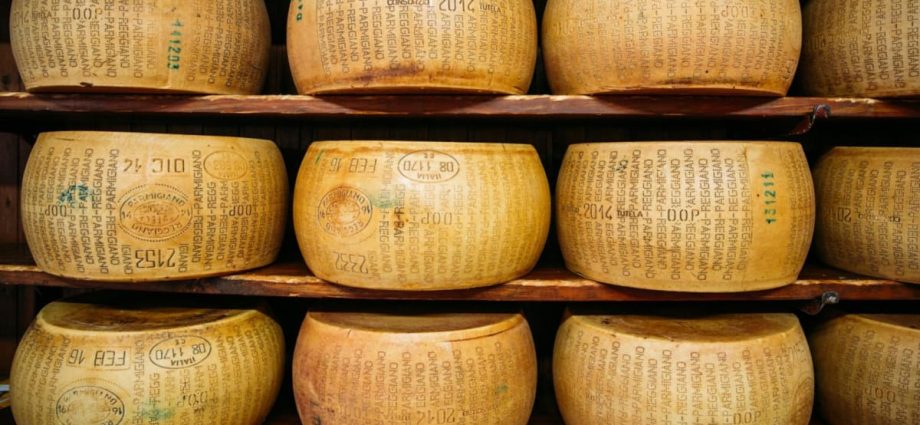

” Parmigiano Reggiano” is a type of geographical indication ( GI ). GI labels cannot be applied to products that do n’t originate from those specific territories because they identify products that are produced there.

The counties of Modena, Parma, and Reggio Emilia in Italy are represented by the GI for the cheese that comes from” the region of the county of Bologna to the left of the River Reno, the region of Mantua to the right of the River Po.”

The Gastrointestinal” Parmigiano Reggiano” was registered in Singapore in June 2019 by the , Consorzio del Formaggio Parmigiano Reggiano , – a collaboration of manufacturers of the cheese.

The Consorzio is tasked by Italy ‘s , Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies to protect interests relating to Parmigiano Reggiano.

According to European Union law, the Consorzio also holds the designation” Parmigiano Reggiano” as a protected designation of origin ( PDO ).

In September 2019, Fonterra filed an application to specify that the Gastrointestinal” Parmigiano Reggiano” does not include the name” Parmesan” as the conditions are not equal.

The company argued that Parmesan had not come from Italy, is not regulated in the same manner as Parmigiano Reggiano, and varies in milk information, regulations, style, color and texture.

When the secretary of GIs allowed Fonterra’s program, the Consorzio filed an opposition to it. A Principal Assistant Registrar granted the criticism, and a High Court judge upheld it.

Fonterra next launched this charm.

” Thoughts DO NOT EXIST IN A VACUUM”

The dispute pitted dictionary definitions of” Parmesan”, put forth by the Consorzio, against examples of how the term is used in the Singapore market, put forth by Fonterra.

The , Consorzio used extracts from the Collins Dictionary, the , Larousse Italian-French Dictionary and the , Cambridge Italian-English Dictionary to argue that” Parmigiano Reggiano” translates to” Parmesan” in both English and French.

Top Justice Prakash, deliving the judge’s view, said the extracts may provide some assistance for the Consorzio’s case, but were not clear.

Because they were compiled by foreign publishers, who might not be aware of the use of” Parmesan” in Singapore.

” Put differently, these definitions are not written in ( and were not designed to reflect ) the language used by visitors in Singapore”, she said.

Words do not occur in a vacuum, she added, and how a certain word is used and the significance or interpretations it holds over time may change depending on the specific environment and local circumstances in which it is used.

She added that the judge was concerned about how the general public perceives Singaporeans and inhabitants as” consumers, not just people passing through.”

She claimed that this typical customer is not a member of Singapore’s expat or European community and that she lacks” special knowledge of cheese.”

In contrast, Fonterra argued that it is” customary” in Singapore for Parmesan to refer to” a hard, dry, easy to grate, or grated cheese with a sharp, slightly sweet, salty flavour”, and for this not to be linked to Parmigiano Reggiano.

More convincing was Fonterra’s argument, which included at least 10 item listings that demonstrated that Parmesan cheese products were sold in Singapore and had clear evidence that they were produced outside of Italy.

They observed noticeable differences in Parmigiano Reggiano and Parmigiano Reggiano items ‘ overall physical characteristics and obverse displays of Parmesan’s country of origin.

Additionally, Fonterra’s information included online catalogs for local stores and Amazon Singapore that categorize Parmigiano Reggiano butter in a different way from Parmesan butter.

The courts and Fonterra concurred that native users have been influenced by how investors categorize Parmesan and Parmigiano Reggiano as” two distinct kinds of cheese products.”

They ruled in favor of Fonterra and placed a restriction on the use of the term” Parmesan” in the Register of GIs, stating that the protection of the GI” Parmigiano Reggiano” should not be used.

The judges also ordered the Consorzio to pay S$ 100, 000 ( S$ 74, 204 ) in costs to Fonterra.