A POWER TRANSITION DICTATED MOSTLY BY THE GENERAL SECRETARY

It is necessary to be vague about these numbers. They have fluctuated over the years, for instance when Xi Jinping in 2012 reduced the number of PBSC members from nine to seven.

In fact, much of the power transition is dictated by the personal desires of the then general secretary, who engages in power broking and haggling with rival factions.

Conventions and norms from the last 20 years seemed to be effective in guiding the selection process, until the last party congress. The retirement age of 68 for Politburo members, future PBSC members being promoted from the current Politburo and successors being installed after the first five-year term all lent an air of predictability to the transition.

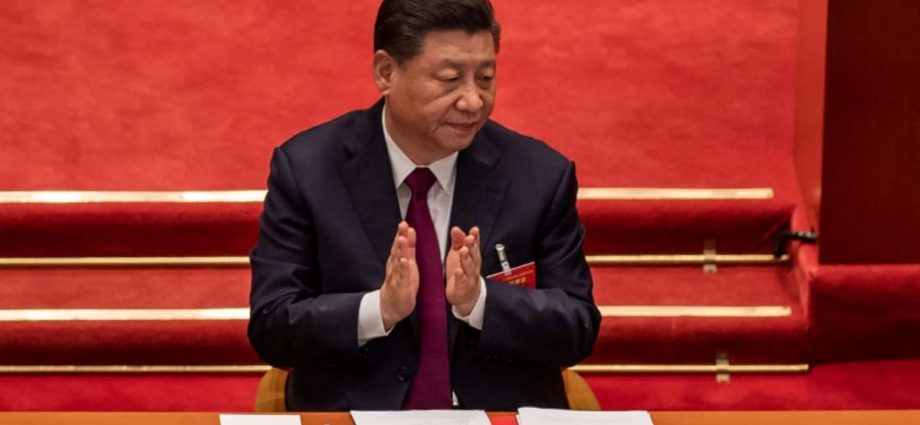

But Xi, 69, has proven willing to tear up some, if not all, of these conventions. In contrast to his two predecessors, he did not install a clear successor to himself, and is in fact set to take on at least a third term, beyond the two (or two and a half) terms of former presidents Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin.

There are no official term limits for CCP general secretaries, allowing Xi to stay on at the top of the party as long as he likes. He also changed the country’s constitution in 2018 to remove term limits for his other role as president.

Importantly, Xi did not remove the term limits for premier, meaning that his rival Li Keqiang, 67, will have to step down from the position in March and thus may be removed from the Politburo at the party congress, despite not being of retirement age.

This makes prognostication around this party congress more challenging as it is unclear if Xi will continue to abide by retirement ages for his allies, or will aim to change the size of the Politburo and PBSC to accommodate more of his proteges.