China’s diplomatic maneuvers over the past weeks have produced all sorts of alarm among members of the Washington foreign policy establishment and media that America’s influence is being supplanted in favor of a new and hostile “world order.”

The failure to see current events in balance-of-power terms goes a long way toward explaining how this situation has come about in the first place.

Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Moscow to affirm the Sino-Russian “no limits partnership” the same week the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant for war crimes against Russian President Vladimir Putin.

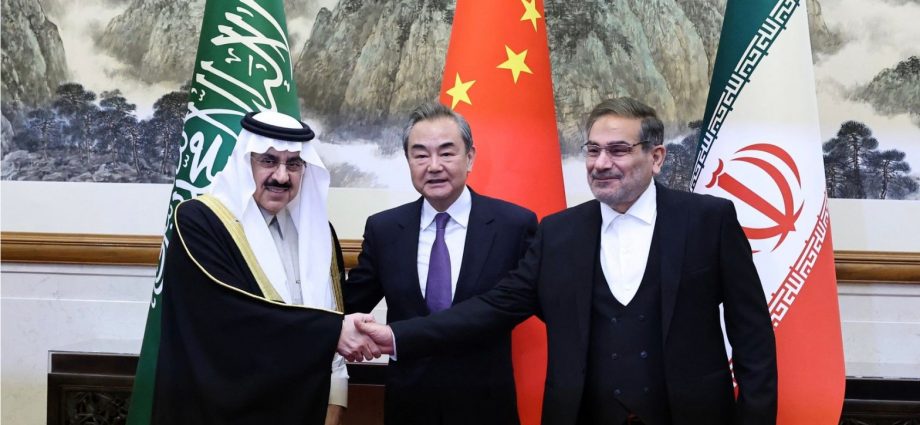

Earlier in the month, China successfully brokered a deal between Saudi Arabia and Iran to re-establish diplomatic ties between the Gulf rivals. In late February, Beijing released a 12-point peace plan for the war in Ukraine to which Kiev signaled both skepticism and openness.

Xi concluded his trip to Moscow by telling Russian President Vladimir Putin “Now there are changes that haven’t happened in 100 years. When we are together, we drive these changes.”

American commentators responded that China is “emerging[…] as the leader of a Eurasian bloc,” that “[a]lliances and rivalries that have governed diplomacy for generations have[…] been upended,” and that an “anti-US world order [is] taking shape.”

The question seems to be limited to “whether this confrontation will heat up, pushing three nuclear powers to the brink of World War III, or merely marks the opening chords of Cold War 2.0. [emphasis mine]”

Few seem interested in asking whether both World War III and Cold War 2.0 can be avoided, or why it is that China has found such a receptive audience for its diplomatic overtures.

A notable exception is Fareed Zakaria’s admirable recent column, which states bluntly that, “America’s unipolar status has corrupted the country’s foreign policy elite. Our foreign policy is all too often an exercise in making demands and issuing threats and condemnations. There is very little effort made to understand the other side’s views or actually negotiate.”

Given the Biden administration’s framing of international politics as a struggle of “democracy vs autocracy” and America’s eschewal of meaningful diplomacy with non-allies, it is unsurprising that Washington would find itself shut out from relations between Beijing, Moscow, Tehran and Riyadh.

Beijing recently stated in unusually strong terms that the US was seeking to “contain” China, an assessment which appears accurate in light of increasingly unambiguous American commitments to Taiwan and Western imposition of export restrictions on technology to China.

Washington’s attempts to isolate and hobble the Russian economy have made it inevitable that Moscow should look east for its energy exports, and increases the possibility of a renminbi-dominated trade zone eroding the global role of the dollar.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s statement that European leaders should turn Putin over to the ICC – a body whose authority the US does not even recognize – not only makes the US look hypocritical in claiming to protect the “rules-based international order,” but is tantamount to a declaration that regime change in Moscow is now official US policy.

This threatens to make the Ukrainian conflict more intractable and dangerous escalation more likely. By issuing an arrest warrant for Putin, the ICC has merely ensured that Moscow can no longer engage in normal diplomacy with the West, including an eventual settlement to the Ukraine war. This all but guarantees that if a broker emerges to negotiate an end to the war, they will not be from the West or reflect its preferences.

While continuing the Trump administration’s hawkish line towards Iran and failing to resuscitate the JCPOA nuclear deal, the Biden administration simultaneously promised to make Saudi Arabia, Tehran’s arch-nemesis, a “pariah.”

Despite decades of picking favorites in the region, the US has diminishing influence in either Riyadh or Jerusalem. US saber-rattling remains the primary motivation for Iran to develop nuclear weapons, an outcome the US claims it wants to avoid. And Saudi Arabia and Syria appear to be on the brink of a rapprochement, this time brokered by Moscow.

China’s mediation of a deal in the Middle East, and its growing involvement in the region, are hardly a bad thing for the US. As my colleague Ben Friedman has recently written, there is little to fear from China filling the “vacuum” left by our disengagement from the region.

Indeed, a cynical realpolitiker could only hope that Beijing would be foolish enough to follow in our footsteps.

The scorecard for American diplomacy over the past few decades is not pretty. The US, which has long sought to avoid the emergence of a hegemon on the Eurasian landmass, has united the other two great powers in an entente bound primarily by opposition to the US.

Despite a rough balance of power in the Middle East which should maximize the United States’ bilateral leverage vis-a-vis all parties, the US has somehow found a way to alienate both of the major players in the Gulf.

All this is to say: who’s isolating whom? As the foreign policy establishment wrings its hands over the formation of hostile alliances and being cut out of the diplomatic loop, it might be worth considering that if you treat everyone else as a “pariah,” you eventually become a pariah yourself.

Christopher McCallion is a Fellow at Defense Priorities. This article is republished with the kind permission of Defense Priorities